Category: theology

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

Richard Beck: hermeneutical self-awareness and a neurotic spiritual nightmare

Richard Beck is on a roll this week with a short series on reading the Bible. In Part #1 yesterday he states premise #1: “Interpreting is inescapable.”

Do the hard work of Biblical study, put in the time and effort to explore, but don’t think you can avoid, in the final analysis, the necessity of making a call. So make it.

Today in Part #2 he highlights the terror that can come when the self-awareness of interpretation is paired with a belief that God will judge you if you get it wrong.

Hermeneutical Self-Awareness + Judgmental God = A Whole Lot of Anxiety

I don’t know that I ever verbalized this thought myself, but I think it drove a lot of my study and reading in my 20s and 30s. Here’s how Beck describes it:

Biblical interpretation is so anxiety-inducing because it’s viewed as so high stakes. Your eternal destiny hangs in the balance, so you have to get it right. And yet, given the hermeneutical situation, you lack any firm guarantees you’ve made the right choice. The whole thing is a neurotic spiritual nightmare. In fact, it’s this nightmare that keeps many Christians from stepping into self-awareness to own and admit their own hermeneutics. It’s more comforting to remain oblivious and un-self-aware.

This put me in mind of a piece I wrote a few years ago where, as an aside, I mentioned that I’m certainly wrong about some percentage of beliefs, but I can’t tell you which ones. Turns out I was interacting with a Richard Beck piece in that one, too. So what do you do? How do you get your way out of Beck’s “neurotic spiritual nightmare”?

By reevaluating one of the terms in the equation.

So I told my students, You have to believe that God’s got your back, that, yes, you might make a mistake. But that mistake isn’t determinative or damning. Just be faithful and humble. You don’t have to have all the correct answers to be loved by your Father. Each of us will carry into heaven a raft of confusions, errors, and misinterpretations of Scripture. It’s unavoidable. We will not score 100% on the final exam.

But don’t worry. Let your heart be at rest. God’s got your back.

As I like to paraphrase something Robert F. Capon said in Between Noon and Three: yes, I’m assuming that God is at heart loving and gracious. Because, let’s face it: if God is a bastard, we’re all screwed.

Richard Beck on finding Common Cause

Richard Beck has a fantastic post out today reflecting on a passage from Barack Obama’s recent memoir and how materialism affects our ability to find common cause across ideological boundaries. Here’s the Obama quote:

T]emperamentally I am sympathetic to a certain strain of conservatism in the sense that I’m not just a materialist. I’m not an economic determinist. I think it’s important, but I think there are things other than stuff and money and income—the religious critique of modern society, that we’ve lost that sense of community.

Here’s my optimistic view. This gives me some hope that it’s possible to make common cause with a certain strand of evangelical or conservative who essentially wants to restore a sense of meaning and purpose and spirituality…a person who believes in notions like stewardship and caring for the least of these: They share this with those on the left who have those same nonmaterialistic impulses but express themselves through a nonreligious prism.

Barack Obama, from A Promised Land

Beck contrasts Obama’s Christian non-materialistic optimism with the atheistic, materialistic pessimism of Ta-Nehisi Coates. Hope, and a pragmatic politics, says Beck, are rooted in a non-materialistic view of reality.

I have leaned politically left in the past decade but been frustrated by the inability of much of the progressive left to share a hopeful view. Beck’s paragraph here turned a light bulb on for me:

…Obama is correct, there are shared values between the materialists and the non-materialists. And those shared values lead us to think we can share “common cause.” We want to. And we try. All the time. But that “common cause” is perpetually undermined as these values are embedded within two very different metaphysical worldviews. In the non-materialist worldview, grace and hope season hate toward political enemies and impatience with the lack of progress in our lifetimes. Non-materialists can play the long game, graciously and hopefully, because they believe in a long game. By contrast, non-materialists [sic, Beck clearly means ‘materialists’ here], since there is no long game and the winners write the history books, will be driven to hate those who oppose them and become violently impatient in the face of conversation, compromise, and incrementalism. Given the pressing urgency of the Revolution hope and grace are moral failures, each dampening the passions needed to change the world.

This is as good an explanation as I’ve seen for the tension between those two groups on the left. Count me among the hopeful non-materialists.

If you go read Beck’s whole post (which you should), you’ll find he also has a couple rather (to borrow a word from my friend Dan) spicy things to say about conservative evangelicals. While I feel his frustration, I wish he would’ve spelled out his reasoning a little bit more to justify such strong words. It would be fascinating to explore why conservative evangelicals, non-materialists in Beck’s schema, seem to so frequently use the materialist’s political playbook. Of course as frequently as Dr. Beck blogs, that piece may already be on its way.

Michael F. Bird on Social Justice as Christian Love

Don’t buy into the lie that all social justice is driven by Marxist ideology. It is not! It is what the prophets commanded, what Jesus expects of his followers, what the church has accepted as normal, and what constitutional democracies with a Christian heritage should aspire to, not in spite of, but precisely because of their Christian heritage.

Let me be clear, love of neighbour requires you to be concerned for the just treatment of your neighbour, whether they are Black, Hispanic, First Peoples, LGBT, migrant, Muslim, working-class, or even Baptist. Any derogation of a Christian’s duty to be concerned about the welfare and just-treatment of their neighbour is an attack on the biblical love command itself.

Michael F. Bird, from “The Fundamentalist War on Wokeness is a War on Christian Love”

Yes, yes, all of this.

The poor you will always have with you?

I just finished up listening to Finding Fred, a short-series podcast about Fred Rogers. Podcast host Carvell Wallace does a really good job of examining the spiritual impact of and what we can learn from Mr. Rogers’ life and ministry. In episode 9, I really appreciated this take on Jesus’ words in Mark 14:

In Mark 14:7, Jesus says “the poor you will always have with you, and you can help them whenever you want, but you will not always have me.” The idea is that one day Jesus would leave His followers. Like all things, he was saying, his presence was impermanent. The only permanent thing is that people will still need help, and we must continue to help those who need it. Notice he didn’t say “I’m gonna be gone so I’m gonna need you to keep on crushing all the bad guys and making sure *they* learn their lessons.” His focus is not on fixing the bad ones, but on helping the needy ones.

I’ve heard plenty of takes on this passage over my years in church, with interpretations all over the place from prioritizing Jesus’ presence to (horribly) suggesting that it’s a fruitless task to try to end poverty because Jesus said we’d always have them. But I really appreciate this particular view of what Jesus was saying. The gospel also tells us that we have help for the “bad people”, too - and we’re all in some sense “bad people” - but when it comes to how this practically applies to living out our faith in the world, caring for the poor and needy seems to be right at the forefront of Jesus’ concern.

Oh, and the whole podcast is worth a listen if you’re into that sort of thing.

Adam Young on Hope and Wrestling with God (2)

Continuing from yesterday, more from Adam Young’s fantastic podcast The Place We Find Ourselves:

Ultimately all disappointment carries with it the sense of a broken appointment with God. I expected God to show up and He didn’t. God is the one who could’ve prevented that illness and He didn’t. He didn’t show up. A broken appointment. A disappointment. One of the reasons we hate hope so much is it requires us to live a “both-and” kind of life.

Christians are meant to constantly hold together both death and resurrection. This is why Paul says we’re to rejoice with those who rejoice and mourn with those who mourn. And many of us would rather live either/or. A life focused solely on resurrection is not hope, it’s optimism. Hope has nothing to do with optimism. Optimism is a denial of the darkness that permeates this world. We don’t live both/and well. We live primarily either/or.

Some of us focus on the darkness of this world, and we see it everywhere, but we have a hard time seeing the thousands of places where the Spirit of God is working everywhere and doing beautiful, redemptive things. Others of us focus on the beauty in this world but we turn a blind eye to all the evil right in front of us.

But Christianity is both/and. A life of both/and means that you are just as apt to be weeping one moment as you are to be laughing the next. You are never far from weeping, because you have your eyes wide open to the darkness of this world. And you are never far from laughing, because you also see the thousands of places of God’s redemptive work all around you.

There’s a spirit of optimism that has invaded the church. It appeals to us because it allows us to escape staying connected to the longings of our hearts. It allows us to turn away from darkness and pain, to pretend it isn’t real.

Much of what you hear in Bible studies and small groups are sentences that shame you for admitting that you have longings, that you groan, that you yearn. What do you do in a group when someone expresses an unfulfilled longing? When someone expresses disappointment over not getting into a particular school, or anger over not being married, or sorrow over not being reconciled to their father? The tendency is to subtly do one of three things:

- encourage them to believe more in the sovereignty of God. “Maybe it’s not God’s will for you to get into that graduate school.”

- Wonder if they are idolizing that which they long for. “It kinda sounds like you’re making an idol out of being married, like that’s too important to you.”

- Suggest that they are wanting too much. “Aren’t your expectations for your Dad too high? Is it really reasonable to hope for reconciliation with your Dad given his background?”

When you respond in one of those three ways, what’s going on? The expression of the other person’s sorrow, anger, disappointment, exposes your deep discomfort with those emotions in your own life. That’s often times what’s happening. And you respond to the person with the same set of sentences you use on yourself to keep your desires under control. You’re not being hypocritical. You’re not even necessarily being cruel. You’re just telling them what you tell yourself.

Are you familiar with the parable of the persistent widow? Jesus tells this story in Luke 18. A widow keeps going back to a judge to demand that she get justice against the person that harms her. And because the widow keeps coming back to insist on her case, the judge finally relents and helps her. And then Jesus says this: “will not God bring about justice for His chosen ones who cry out to Him day and night. Will He keep putting them off?”

Here’s the point: it’s not called “the parable of the widow who learned to surrender to God’s will”. The whole point is that she refused to take “no” for an answer. She knew nothing of “maybe it’s not God’s will for me to get justice against this particular adversary”. She refused to take “no” for an answer.

So, how much hope do you have? The danger is thinking you just need to conjure up more hope. Two problems with that, first, that you can’t. But the bigger problem is that you actually have far more hope than you realize. You may not be fond of it, but will you have the integrity to confess how much hope you actually still have.

Think of all the disappointments that you’ve endured in your life. Think of all the prayers you’ve prayed, all the times you’ve called out to God and he has not come through for you the way you’ve wanted. And yet. You’re still interested in God. You’re still talking to God. You’re still pursuing God. You haven’t given up on God. You’re wanting healing or help in some are of your life, and you’ve gone to God about it, and the healing or the help has not come. That’s tormenting. And yet you still come back to God. You still pursue God. You think about God. You may pray, you may read Scripture, but you keep coming back. The Bible calls that hope.

The people who have suffered trauma, abuse, heartache, often have immense love for Jesus and immense hope. They often hate the hope that they have, but they have it. What Paul wrote in Romans seems to be a good description of what happens in their life: suffering produces perseverance; perseverance, character; and character, hope. Do the math: suffering leads often to creation of a robust hope in the very people who have the least evidence to suggest that hope is reasonable.

In a very real sense, our hope is not merely in God - our hope IS God. The essence of rescue is not primarily receiving that which you asked for, but rather experiencing the responsiveness of God to the hurt in your heart. It’s not the school or the healing or the relationship that satisfies us; it is the satisfaction, the rest of knowing that I have a Father in heaven who is deeply involved in the desires of my heart. I have a Father that cares. I have a Father that responds. Will you hope? Will you entertain your longings and give them an audience before God? Will you give your disappointments back to God to keep your desires alive?

Adam Young on Hope and Wrestling with God (1)

A friend recently pointed me to Adam Young’s podcast The Place We Find Ourselves. As a licensed social worker who has certifications in counseling and also an MDiv, Young thoughtfully combines psychological and emotional insights with Biblical truth in a way I haven’t encountered before. This morning the last 8 minutes of his Episode 18 discussion on hope and wrestling with God were just golden. The quote is long so I’ll split it into a couple posts.

God says “those who hope in Me won’t be disappointed”…. the difficulty is that you don’t know which of your longings God will meet in the land of the living, and you don’t want to wrestle with God about meeting those particular desires. Herein lies the biggest reason we hate hope: hope forces us to wrestle with God.

Most wrestling with God is avoided by a very simple phrase: “if it be Your will”. You express a desire to God and then you tack on this phrase. “If it be Your will.” “Not my will, but Yours be done.” Right? That’s the sentence. And it is a beautiful sentence, as long as it comes after a 12-round match of wrestling with God.

Now, you may be thinking ‘wait a minute, aren’t we supposed to surrender our will to God’s will?’ Yes! But that’s just the point. You’re called to surrender your will to God’s will. And what does surrender mean? It is to give in after a long, drawn-out bloody war. You can’t surrender until you have fought with God. And generals never surrender until they have fought to the end of their strength. Surrender only comes in a moment of exhaustion.

If you’re not exhausted from fighting with God, from bringing the longings of your heart repeatedly to God, then the words “not my will but Yours be done” aren’t words of surrender. They are words to avoid hope. Which is to avoid warring and wrestling with your God. You can’t talk about hope without talking about wrestling.

If you don’t find yourself regularly wrestling with God, chances are you don’t live with much hope. Because hope creates longing in you, and unfulfilled longings drive you to God, because God is the only one that can satisfy the longing. God is the only one that can make that thing happen. Until you take the risk of hoping that God will fulfill the desires of your heart in this life, until you bring your disappointment and anger to Him again and again, God will always remain strangely impersonal to you. You might know him as God the savior of the world, but you won’t know Him as what the Psalmists call ’the God of my rescue’.

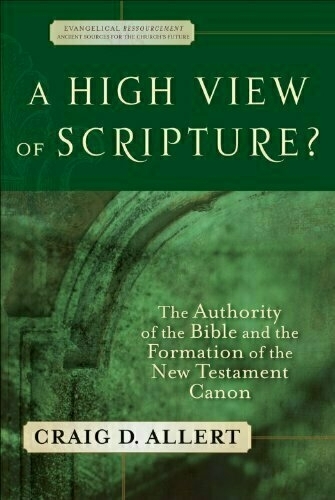

A High View of Scripture?

About a year ago I started getting interested in historical criticism as it relates to the Bible. As I explored and read several books, I kept wondering: where was this discussion, or even the acknowledgement of this topic, in the evangelical tradition in which I grew up?

Most all I’ve ever encountered in evangelicalism in this area is that the Bible is made of up 66 books, that they’re “inspired” and “inerrant”, with varying levels of nuance about what those terms mean. I can’t remember ever hearing a discussion about how, when, or by whom the books of the OT and NT were assembled; only that that the collection of 66 is canonical and that’s basically that.

Where, I lamented on Twitter, were any evangelical takes on anything approaching historical criticism? This question did lead to a dear Episcopal priest in Wisconsin sending me three of his seminary textbooks on the topic (thanks again, Rev. Mike!), but from the evangelical perspective, I didn’t encounter anything much more nuanced than what I found on the “God said it, I believe it, that settles it” bumper sticker.

Enter Dr. Craig Allert’s A High View of Scripture?: The Authority of the Bible and the Formation of the New Testament Canon. Allert is a professing evangelical and professor at Trinity Western University in British Columbia. A High View of Scripture? is published by Baker Academic as a part of their “Evangelical Ressourcement” series. The book’s purpose, says Allert in the introduction, is to “investigat[e] the implications of the formation of the New Testament canon on evangelical doctrines of Scripture.”

This study has been lacking in evangelicalism, he says, and we are poorer for it.

[The] neglect of the canon process has left evangelicals with an inadequate understanding of the very Bible we view and appropriate as authoritative. For the most part, evangelicals seem unconcerned with how we actually got our Bible, and when we do show interest, we rarely relate the implications of this concern to how this might affect a doctrine of Scripture. This is ironic since evangelicals hav been quite loud in proclaiming the ultimate authority of the Bible; surely that proclamation should be informed about how the Bible came to be.

Dr. Craig Allert, A High View of Scripture?, p. 12

In A High View of Scripture?, Allert draws heavily on the church fathers and early church writings to distinguish between Scripture and canon, to explore how the word “inspiration” was used early on to describe various writings and practices, both canonical and not, and how the church wrestled with the question of what writings were considered canonical well into the 4th century.

After taking a few chapters to overview the history, Allert asks some hard questions about how we should have that history inform our doctrine of Scripture. How should it affect our understanding of Scripture when we acknowledge that these “inspired” texts were not delivered on a platter as an autographed, bound volume, but were assembled and agreed upon by the church over a period of more than three hundred years?

Allert affirms the authority and inspiration of Scripture, but balks at “inerrancy”, since the Scripture doesn’t use that word of itself, and since the definitions of “inerrancy” are challenging, frequently seeming to be constructed post hoc in support of the theologian’s predetermined interpretations. While evangelicals prefer to be known as focused on “the Book” and dismissive of “tradition”, Allert insists that we can’t have a healthy doctrine and understanding of Scripture without acknowledging and embracing the fact that the early church played a key role in the formation of the canon of Scripture and what it means.

I very much appreciated A High View of Scripture? and would highly recommend it to my evangelical friends. We need more of this sort of thing. Not to use historical “criticism” to diminish the Scripture, but to reject the impulse to skittishly rush past canon formation on our way to Scriptural authority, and to recognize that our reliance on the Scripture need not be weakened by acknowledgement of the human participation in its writing and assembly.

A justice not to be feared but to be longed for

Here is my servant, whom I uphold

my chosen, in whom my soul delights

I have put my spirit upon him;

he will bring forth justice to the nations.

He will not cry or lift up his voice,

or make it heard in the street;

a bruised reed he will not break,

and a dimly burning wick he will not quench;

He will not grow faint or be crushed until he has established justice in the earth;

and the coastlands wait for his teaching.

Isaiah 42:1-4, NRSV

Often when I have read this passage or ones like it my first inclination is to think of this “justice” being established as a punishing sort of justice. God sends his servant, the Messiah, to justly deal with sin by punishing the bad guys. That’s largely how we’ve been taught, at least within my faith tradition, to think about God’s justice - as something punitive and to be feared.

But then we get to Matthew 12.

The Pharisees confront Jesus about his disciples picking grain on the sabbath. Jesus rebukes the Pharisees. “If you had known what this means, ‘I desire mercy and not sacrifice,’ you would not have condemned the guiltless.” Jesus then goes into the synagogue and provokes them further by healing a man on the sabbath. Which drives the Pharisees to start conspiring how to destroy Jesus.

When Jesus became aware of this [that the Pharisees were conspiring to destroy him], he departed. Many crowds followed him, and he cured all of them, and he ordered them not to make him known. This was to fulfill what had been spoken through the prophet Isaiah:

“Here is my servant, whom I have chosen,

my beloved, with whom my soul is well pleased.

I will put my Spirit upon him,

and he will proclaim justice to the Gentiles.

He will not wrangle or cry aloud,

nor will anyone hear his voice in the streets.

He will not break a bruised reed

or quench a smoldering wick

until he brings justice to victory.

And in his name the Gentiles will hope.”

Matthew 12:15-21, NRSV

This brought me up short when I read it this morning. This is what it looked like for Jesus to bring forth and establish justice. He rebuked the abusive religious traditions and hypocritical religious teachers. He healed. He didn’t just heal a few of them - read the words! “He cured all of them”!

What if, when we think about God’s justice, this is what comes to mind? Not a fearsome, punishing justice against sinners, but a loving restoration? A rebuke of abusive tradition? Jesus taking broken lives and bodies and making them whole? A justice that says ’this is not how things were intended to be, and so I am making things right again’?

This is a justice not to be feared but to be longed for.

Richard Beck: Love in Post-Progressive Christianity

Richard Beck has a series going on an approach he calls “post-progressive Christianity”. I’ve appreciated it a lot as he works to identify the good things progressive strains of Christianity have to offer but also where they fall short. I found his recent post on Love to particularly hit the mark:

All that to say, progressive Christians, because they preach inclusion and tolerance, tend to see themselves as lovers in contrast to their more judgmental evangelical counterparts. And in the eyes of the world, yes, progressive Christians are more tolerant and inclusive, more likely to welcome the “sinners” who are shunned by evangelical churches.

And yet, when it comes to cruciform love, loving our enemies, progressive Christians are no more loving than evangelical Christians. That’s a hard thing to say, but are progressive Christians doing a better job at loving the people they consider wicked? As we are all well aware, there is an intolerance associated with tolerance, and this intolerance has left its mark upon how love is expressed with progressive Christianity, although many try valiantly to resist this influence. The sad irony is that an ideal of tolerance simply creates a new definition of “evil.” And once that “evil” group is identified, it becomes really hard to love them. In fact, it’s downright immoral to love them…

Brian Zahnd made a very similar point at the Water to Wine Gathering last month: when you hate the haters, hate wins. The challenge is to remain lovers, for the love of many will grow cold.

Whether we claim the label “progressive” or “conservative” or no label at all beside “Christian”, the distinguishing mark of cruciform (cross-shaped) Christianity is that of love, even (especially?) love for enemy.