Category: Marilynne Robinson

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

My 2024 Reading In Review

Another year full of books! (Previous summaries: 2023,2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007…

I read 63 books for the year, a few less than last year. I keep saying I’m going to stop logging to Goodreads, but it’s so easy and I’ve kept track there for so long that I still do it. I also keep my Bookshelf site over on my own website which I prefer to link you to instead.

The list is almost exactly a 50/50 split between fiction and non-fiction.

Here’s the full list of reading, with particular standouts noted in bold:

Theology / Ministry

- Varieties of Christian Universalism by David W. Congdon

- The Lost World of the Prophets by John H. Walton

- Reading Genesis by Marilynne Robinson

- From The Maccabees to The Mishnah by Shaye J. D. Cohen

- A Window to the Divine by Zachary Hayes

- Wounded Pastors by Carol Howard Merritt

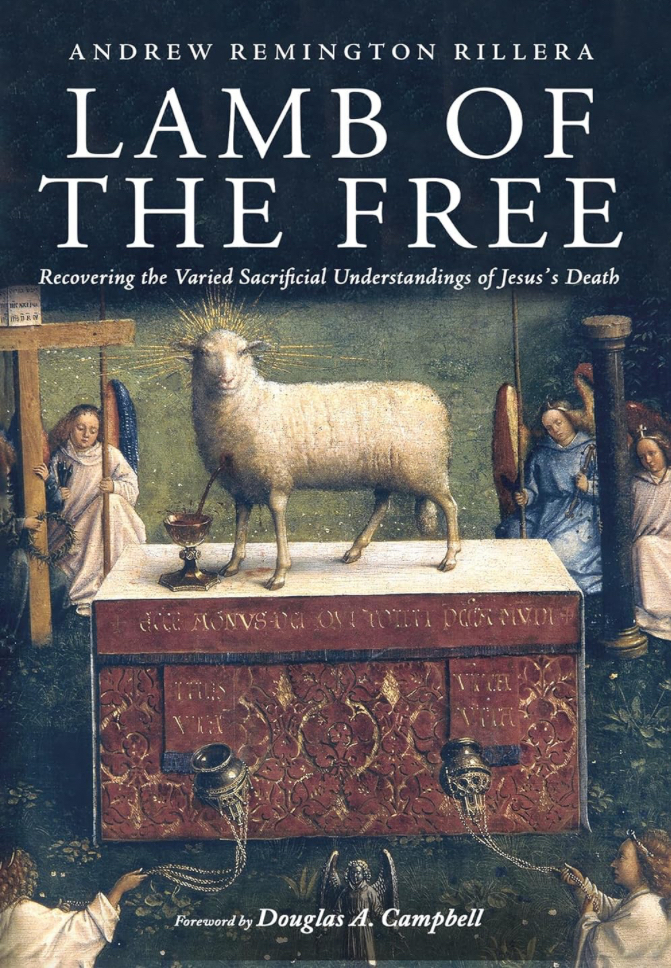

- Lamb of the Free by Andrew Remington Rillera

- Making All Things New by Ilia Delio

- Reaching Out by Henri J. M. Nouwen

- The Experience of God by David Bentley Hart

- The Hours of the Universe by Ilia Delio

- A Private and Public Faith by William Stringfellow

I wrote about the Zachary Hayes book this summer. It’s small and delightful. And I’m looking forward to revisiting Andrew Remington Rillera’s Lamb of the Free as a part of a book club starting next week.

Science and History

- The Kingdom, The Power, and The Glory by Tim Alberta

- Finding Zero by Amir D. Aczel

- The Murder of Professor Schlick by David Edmonds

- Ringmaster by Abraham Riesman

- The Grand Contraption by David Park

- Neurotribes by Steve Silberman (RIP)

- 3 Shades of Blue by James Kaplan

- A General Theory of Love by Thomas Lewis

- Space Oddities by Harry Cliff

- The Hidden Spring by Mark Solms

- Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman

- Black AF History by Michael Harriot

- Debt by David Graeber

Ringmaster is a biography/history of Vince McMahon and his WWE empire. It’s a must-read as we enter four more years of a Trump presidency that will be about image and story line rather than truth.

Graeber’s book was fantastic as social science but prompted me to think theologically.

Memoir and Biography

- This American Ex-Wife by Lyz Lenz

- The Exvangelicals by Sarah McCammon

- An Autobiography, or, The Story of My Experiments With Truth by Mahatma Gandhi

Other Miscellaneous Non-Fiction

- Cultish: The Language of Fanaticism by Amanda Montell

- All Things Are Too Small by Becca Rothfeld

- Never Split the Difference by Chris Voss

- How to Read a Book by Mortimer Adler and Charles Van Doren

Fiction

- The Downloaded by Robert J. Sawyer

- Hell Is a World Without You by Jason Kirk

- In Universes by Emet North

- Exordia by Seth Dickinson

- Through a Forest of Stars by David Jeffrey

- Sun Wolf by David Jeffrey

- The Practice, The Horizon, and The Chain by Sofia Samatar

- The Light Within Darkness by David Jeffrey

- The Future by Naomi Alderman

- Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse

- The Year of the Locust by Terry Hayes

- Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar

- The Revisionaries by A. R. Moxon

- Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders

- I Cheerfully Refuse by Leif Enger

- The Midnight Line by Lee Child

- Blue Moon by Lee Child

- Do We Not Bleed? by Daniel Taylor

- Heavenbreaker by Sara Wolf

- Red Side Story by Jasper Fforde

- Airframe by Michael Crichton

- Extinction by Douglas Preston

- Killing Floor by Lee Child

- Die Trying by Lee Child

- Moonbound by Robin Sloan

- Some Desperate Glory by Emily Tesh

- Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner

- 2054 by Elliot Ackerman

- Shadow of Doubt by Brad Thor

- Tripwire by Lee Child

- Spark by John Twelve Hawks (unintentional re-read)

Summary

I didn’t realize until I typed up the list for this post that I had run through so much fiction. Guess it was a year I needed some lighter reading. I did a quick count on the books on my to-read shelf and if I constrained myself to just those books, I might have it cleaned off by this time next year. (I mean, that’s unlikely, but it’s a decent goal.)

Marilynne Robinson on Community and Absence

Posting this quote from Marilynne Robinson here just so I have it at hand for later use:

To speak in the terms that are familiar to us all, there was a moment in which Jesus, as a man, a physical presence, left that supper at Emmaus. His leave-taking was a profound event for which the supper itself was precursor. Presence is a great mystery, and presence in absence, which Jesus promised and has epitomized, is, at a human scale, a great reality for all of us in the course of ordinary life.

I am persuaded for the moment that this is in fact the basis of community. I would say, for the moment, that community, at least community larger than the immediate family, consists very largely of imaginative love for people we do not know or whom we know very slightly.

In full context, she’s talking about community with fictional characters and authors here, but this rings so true to me in a world full of online communities.

Finished reading: Reading Genesis by Marilynne Robinson

I wasn’t sure what to expect from Robinson writing on Genesis, but I enjoy her writing enough it was definitely something I was going to read. Structured as a narrative commentary, Robinson doesn’t employ chapter breaks or other touchpoints within the text itself. It’s fascinating to read a commentary by a Christian writer who takes the text seriously but not necessarily literally. If there is a broad “point” to her book, it is to feature the uniqueness of Genesis among the Ancient Near Eastern texts, and to highlight the theme of unmerited grace that runs through it. From God’s forgiveness of Cain to Joseph’s forgiveness of his brothers, Robinson tells us that Genesis is set apart from the other ANE texts this way.

I appreciated her book, but didn’t enjoy it as much as reading her essays. I need to pick them up for a re-read.

The extraordinary moment...

Again from Marilynne Robinson’s The Givenness of Things, from a chapter titled “Proofs”, a paragraph (which I am splitting up for online readability) about the extraordinary experience of Christian preaching:

The great importance in Calvinist tradition of preaching makes the theology that gave rise to the practice of it a subject of interest. As a layperson who has spent a great many hours listening to sermons, I have an other than academic interest in preaching, an interest in the hope I, and so many others, bring into the extraordinary moment when someone attempts to speak in good faith, about something that matters, to people who attempt to listen in good faith. The circumstance is moving in itself, since we poor mortals are so far enmeshed in our frauds and shenanigans, not to mention our self-deceptions, that a serious attempt at meaning, spoken and heard, is quite exceptional. It has a very special character.

My church is across the street from a university, where good souls teach with all sincerity - the factually true, insofar as this can really be known; the history of nations, insofar as this can be faithfully reported; the qualities of an art, insofar as they can be put into words. But to speak in one’s own person and voice to others who listen from the thick of their endlessly various situations, about what truly are or ought to be matters of life and death, this is a singular thing. For this we come to church.

Sabbath is a way of life...

More from Marilynne Robinson’s The Givenness of Things, from a chapter titled “Decline”:

The Sabbath has a way of doing just what it was meant to do, sheltering one day in seven from the demands of economics. Its benefits cannot be commercialized. Leisure, by way of contrast, is highly commercialized. But leisure is seldom more than a bit of time ransomed from habitual stress. Sabbath is a way of life, one long since gone from this country, of course, due to secularizing trends, which are really economic pressures that have excluded rest as an option, first of all from those most in need of it.

Marilynne Robinson on Cultural Pessimism

I’ve been a fan of Marilynne Robinson’s for a while now, though perhaps even more for her volumes of essays than for her award-winning novels.

(As a complete aside: Robinson lives in Iowa City, and my fantasy flight back to Cedar Rapids is to end up seated next to her for the 45-minute flight from some hub airport. In my head we could have some meaningful conversation about theology; in practice it’d take me nearly all of the flight to work up the courage to say hello. Ah well.)

I’m reading through The Givenness of Things right now and enjoying it immensely. I’ve found several passages that I’d like to share, but I’ll just start with one in this post, from a chapter titled “Reformation”. (I’ve split it into a couple chunks to make it easier to read; in the original this is a single paragraph.)

Cultural pessimism is always fashionable, and, since we are human, there are always grounds for it. It has the negative consequence of depressing the level of aspiration, the sense of the possible. And from time to time it has the extremely negative consequence of encouraging a kind of somber panic, a collective dream-state in which recourse to terrible remedies is inspired by delusions of mortal threat. If there is anything in the life of any culture or period that gives good grounds for alarm, it is the rise of cultural pessimism, whose major passion is bitter hostility toward many or most of the people within the very culture the pessimists always feel they are intent on rescuing.

When panic on one side is creating alarm on the other, it is easy to forget that there are always as good grounds for optimism as for pessimism - exactly the same grounds, in fact - that is, because we are human. We still have every potential for good we have ever had, and the same presumptive claim to respect, our own respect and one another’s. We are still creatures of singular interest and value, agile of soul as we have always been and as we will continue to be even despite our errors and depredations, for as long as we abide on this earth. To value one another is our greatest safety, and to indulge in fear and contempt is our gravest error.

I aspire to this sort of grounded, optimistic faith.

About those doubts and questions

From Marilynne Robinson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Gilead:

I’m not saying never doubt or question. The Lord gave you a mind so that you would make honest use of it. I’m saying you must be sure that the doubts and questions are your own, not, so to speak, the mustache and walking stick that happen to be the fashion of any particular moment.

Sage advice, that.

"To be astonishing seems to be the mark of God’s great acts..."

I’m sure I heard the name Marilynne Robinson several years ago when her novel Gilead won the Pulitzer Prize. She does live just down the road in Iowa City, after all. As I recall I even borrowed the book from the library and got bogged down in it pretty quickly. (Maybe I wasn’t ready for it a decade ago.)

Then last year on a whim I borrowed When I Was A Child I Read Books from the library; a slim volume of essays that turned into one of my favorite reads of the year. (I need to go back and read it again.)

Robinson’s writing reveals her as a delightful conundrum theologically. Raised Presbyterian, now part of the United Church of Christ, yet rather than embracing the theological ambiguity of the UCC she speaks fondly of John Calvin, clearly takes the Scriptures seriously, and reveals a deep humanism and care for people created in God’s image.

A recent interview of Robinson by The American Conservative prompted me to write this post, and it’s definitely worth a read. Robinson stakes her claim to ’liberal Protestantism’ that she describes as being ‘grounded in Calvinism’.

When asked her thoughts about the association of Christianity with the American right-wing, she said this:

Well, what is a Christian, after all? Can we say that most of us are defined by the belief that Jesus Christ made the most gracious gift of his life and death for our redemption? Then what does he deserve from us? He said we are to love our enemies, to turn the other cheek. Granted, these are difficult teachings. But does our most gracious Lord deserve to have his name associated with concealed weapons and stand-your-ground laws, things that fly in the face of his teaching and example? Does he say anywhere that we exist primarily to drive an economy and flourish in it? He says precisely the opposite. Surely we all know this. I suspect that the association of Christianity with positions that would not survive a glance at the Gospels or the Epistles is opportunistic, and that if the actual Christians raised these questions those whose real commitments are to money and hostility and potential violence would drop the pretense and walk away.

Strong stuff. And I love the spirit of what she says when asked about her views of the Second Coming:

I expect to be very much surprised by the Second Coming. I would never have imagined the Incarnation or the Resurrection. To be astonishing seems to be the mark of God’s great acts—who could have imagined Creation? On these grounds it seems like presumption to me to treat what can only be speculation as if it were even tentative knowledge. I expect the goodness of God and the preciousness of Creation to be realized fully and eternally. I expect us all to receive a great instruction in the absolute nature of grace.

I went to the library yesterday and picked up a copy of Gilead. It’s time to give it another try. Then it’s time to go back and find Robinson’s other novels and essays. We are blessed to have a thinker and writer of Robinson’s grace and skill sharing with us.

"When I Was A Child I Read Books" by Marilynne Robinson

I’ve gotten to the point where, unless I’m looking for a specific book, I don’t even visit the main stacks of the library any more. Instead, I head right for the “new books” section, and pick up a recent novel or biography.

While perusing the new book shelf during my last visit, I picked up Marilynne Robinson’s book of essays on a whim. It’s not the type of book I usually pick up, but it looked interesting enough, and short enough that I had a chance to get through it without getting majorly bogged down.

Marilynne Robinson teaches at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop at the U of I. She’s probably best known for her novel Gilead, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Literature in 2005. It ends up, though, that she’s published more essays than she has novels, and, if her latest volume is any indication, her essays are really good.

When I Was A Child I Read Books is a short, dense collection of essays that perhaps have less to do with reading books, and more to do with the intersection of faith and the current American religious culture. Robinson stakes out a middle ground that on one hand rejects the liberal theology of mainstream Christian denominations, while simultaneously opposing the apparent hard, uncaring line heard too often from the far right wing.

I have felt for a long time that our idea of what a human being is has grown oppressively small and dull.

Robinson’s essays call us to accept and embrace the mystery and beauty of being human. She urges us to give others the benefit of the doubt, to live with compassion towards even (especially?) those who we don’t know or understand.

There is at present a dearth of humane imagination for the integrity and mystery of other lives.

When I Was A Child I Read Books was slow going, but only because there was such richness to savor on every page. If you have the time for some thoughtful reading, I’d recommend this book.