Category: lgbtqia

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

On LGBTQIA+ Affirmation

June 2022 was quite a month for me. It started with the death of a long-time friend. It ended with my being on a phone call with my father while he experienced a stroke-like event. (Turns out: not a stroke. He’s home, and doing ok. Hallelujah.) In the middle was a thing called Pride Month, which had a little more visibility at our home than usual. Two of my kids identify as LGBTQIA+ and have embraced visibility more this year than ever before. (I got their permission to say this here.) So, one of these things is not like the other, but stick with me here and I’ll connect the dots.

Part 1: Online Community

Since Geof died last month, the online community he fostered for nearly 20 years (referred to as “RMFO” for reasons long since forgotten) has been renewed. I have hosted two Zoom “happy hour” calls, and both times 15-20 people have joined, chatted for 2-3 hours, and left with a request that we schedule another one. We have spent these hours catching up on life and recounting our own personal histories as they interact with the RMFO community: singles who met their future spouses in the group; couples once struggling to conceive who now have teenagers; marriages, divorces, job changes, moves, faith evolutions. Online friendships have led to “real-life” friendships, meet-ups, and job opportunities. At the end of the first call I realized that, while I had long considered many of these people meaningful to me, the call helped me realize that I was meaningful to them, too. My thought last week as I closed out the second call: this is the closest thing I’ve had to a healthy, functioning community in my adult life.

During last week’s call I talked about how my own personal views on some issues have evolved over the years, and how I have struggled to find an in-person community (specifically, a church community) where that evolution was welcome. Share those views too loudly and you will be welcome to find some other church to serve and worship at. Five years of quiet discomfort weren’t enough to dislodge me from my last church; their tepid COVID response was the straw that gave me the courage to break the proverbial camel’s back. Two years later I still haven’t found a new place to join. If I’m honest, I haven’t really looked too hard.

Part 2: My Dad

My dad is talking a little slower thanks to the medications he’s on after his health scare, but he’s not talking any less. When we talked last week after he got home from the hospital, we spent a while comparing current reading lists and discussing how some of the books I have given him over the years have helped guide his journey out of a fundamentalist faith into something much more open and gracious. That’s his story to tell, not mine. But what he said toward the end of the call stuck with me: that coming close to death now makes him unwilling to stay quiet on the topics important to him. And I thought to myself: that’s a lesson I should take to heart here in my 40s.

Part 3: Chuck Pearson

Chuck Pearson is a friend of one of the RMFO guys — someone I have never met but have followed on Twitter for years. Last week he posted a beautiful essay about his journey leaving a tenured professorship at a Southern Baptist university when he knew he would eventually be required to sign a “personal lifestyle statement” that would “[force] him to disown his LGBTQ+ friends and family”. Chuck ultimately found a post at another university, but still sat quiet about the topic of LGBTQ+ inclusion:

Ultimately, it stayed private because I didn’t want to burn those bridges. Even as I made that realization that I had to choose between two sides I cared about deeply, I couldn’t bring myself to take that final step of declaring my choice.

In his essay, Chuck quotes from an Alan Jacobs essay from 2014 that argues for Christians to stand firm against the cultural evolution of views on sexuality. Here is Jacobs’ conclusion [preserving the emphasis from the original post]:

Either throughout your history or at some significant point in your history you let your views on a massively important issue be shaped largely by what was acceptable in the cultural circles within which you hoped to be welcome. How do you plan to keep that from happening again?

Clearly Jacobs has in mind a call to resist the desire to be welcomed by “the world” by accepting “worldly” views on sexuality. But for me his question takes the exact opposite orientation. How long have I been convinced about full acceptance of LGBTQIA+ people in the church but been afraid to say so, knowing that it would make me unwelcome in the evangelical church circles I have run in my entire life? Far too long.

Conclusion

So let me make a long-overdue statement as clearly as I can. I am a Christian, and I affirm those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual as they are, unconditionally, including their full inclusion into the assembled body of Christ known as the local church. I know there are those who would say I cannot hold that view and be a Christian. I reject that assertion.

There are multiple serious approaches to the Scripture on the topic which I will not go into here. Suffice it for now to say that you cannot read Scripture as a flat text. It is the product of thousands of years of God’s progressive revelation as understood and recorded by humans. In the end you have to come to some conclusion on which texts capture most clearly the essence of who God is, and use those as the framework from which to understand the rest.

And so, to quote Brian Zahnd:

God is like Jesus.

God has always been like Jesus.

There has never been a time when God was not like Jesus.

We have not always known what God is like—

But now we do.

Jesus taught these two principles in summation of all the teaching: love God with everything you have, and love your neighbor as yourself. He embraced the outsiders and rebuked the self-righteous. He called us to follow Him in lives of self-sacrificial love.

In addition to Jesus’ teaching, we have the witness of the Holy Spirit in the lives of our LGBTQIA+ brothers and sisters — so many dear, tender souls who consistently model what it means to follow Jesus, even in the midst of a church that rarely welcomes them. And to that I can only respond as the Apostle Peter did after first seeing the conversion of Gentiles to Christ: “Can anyone object to their being baptized, now that they have received the Holy Spirit just as we did?” (Acts 10:47)

Rachel Held Evans summarized it this way: “The apostles remembered what many modern Christians tend to forget—that what makes the gospel offensive isn’t who it keeps out but who it lets in.”

To this I say: Amen. May it be so.

Recent reading: Queer Theology by Linn Marie Tonstad

The past couple months I’ve been participating in a reading group hosted by Matt Tebbe. (Matt leads an Anglican church plant in the Indianapolis area.) This group, framed around “Reading for the Sake of Others”, is focused on reading outside of the usual conservative white male authors that fill our reading piles. The intention is not that we will agree with everything we read—indeed, if we do, we’re probably not reading widely enough—but to expand our horizons, to acknowledge our blind spots, and to stretch us at least a little.

Our first book in March, then, is one I would likely have never picked up otherwise: Queer Theology by Yale Divinity School professor Linn Marie Tonstad. It’s a short book—less than 200 pages—but provided me a lot to think about. I won’t try to summarize it all here, but wanted to recount some thoughts that I scribbled out on Twitter last night.

- I appreciate the focus in queer theology on the reality of embodied existence. Our embodied experience is complex, messy, and should not be ignored. We should pay more attention to what it means for Jesus to have been incarnate.

- I appreciated the thought that, though we might hope or imagine otherwise, we are not “self-transparent, rational, autonomous individuals”—i.e., that we are to some extent unable to make choices that determine our outcomes. This means that the categories that we learn and filter our view of life through are so built-in that they are beyond our control and will inevitably affect our view of everything, but especially of the non-normative.

- I appreciate an approach that acknowledges that there are queer members of the body of Christ, and works from that given to then think through what this might mean about Christ’s and the church’s nature.

- I am challenged by the assertion that if (since) Christianity is “a story in which each person is the object of God’s care, attention, and love”, then Christians should reckon more seriously about those implications, aprticularly regarding politics, economics, and sexuality. This quote reminded me a lot of reading Robert Capon: “The question is this: what does an economy of infinite, inexhaustible love look like?”

- I am conflicted about the queer theology assertion that our sexual self and experience is so fundamental to the experience of being a spiritual human being. The theology I have grown up learning is heteronormative, insisting that other experiences/desires are sinful. Yet, it’s hard to deny the assertion that our sexual selves are fundamental to our human experience, and thus to our spiritual being as well.

- Finally, I really appreciate the language of “human thriving” to describe that which God wants and we should strive for. I have read others (I forget who) who describe sin as that which is contrary to human flourishing, and that’s been a helpful frame for me to think through sin, the result of sin, and the goodness of the law.

I am definitely looking forward to the group discussion on this one next week!

Andrew Sullivan on the Gay Wedding Cake Case

I miss Andrew Sullivan. I’m glad the guy detached a bit - the pace of his daily blogging was incredible, no surprise it wasn’t sustainable - but he has a unique and important voice on issues of our time. So it was no surprise to me that his weekly column addressing the Gay Wedding Cake case is a must read.

I find myself pretty much in alignment with Andrew’s conflicted take. I’d highly recommend reading the whole thing - it’s not too long - but I’ll quote just one pithy paragraph.

In other words, if the liberals were more liberal, and the Christians more Christian, this case would never have existed. It tells you a great deal about the decadence of our culture that it does.

-- New York Magazine: The Case for the Baker in the Gay-Wedding Culture War

Finished Reading: People to Be Loved by Preston Sprinkle

I’ve honestly been avoiding books on the topic of Christian views on homosexuality because I’ve become so familiar and fatigued with the arguments over the past decade. But this one by Preston Sprinkle caught my attention and was on sale cheap at the time on Amazon, so I downloaded it to my Kindle app and gave it a go.

Sprinkle sets out to take an evenhanded look through the Bible at the various key texts that have been used to argue for both the Affirming and Non-Affirming positions regarding homosexual practice. I’ll give him credit - for the majority of the book he was even enough that I had no real inkling of which side he was going to come down on. Well done!

The beginning of the chapter seven wherein he finally reaches a conclusion (spoiler alert: he’s in the Non-Affirming camp) is where the shine started to come off. Not because of the conclusion he reached, but because of how he addresses 1 Corinthians 6. What do malakoi and arsenokoites really mean? How should they be translated? “Affirming scholars”, he tells us, “generally argue that these words are too ambiguous.” OK. A “brilliant New Testament scholar at Yale University” concludes that nobody can really know exactly what they mean. Later on about arsenokoites, he tells us that “[s]cholars differ widely on what this word means”. But after setting this scene of ambiguity, he essentially says what do these words mean? Let me explain it all to you in 20 pages in a popular-level book. He lost me at that point.

There is good stuff to take away from Sprinkle’s book regardless of which camp you find yourself in. I appreciate his focus on loving individuals rather than flattening them to “an issue”. And if you’re not familiar with the various approaches Christians have taken toward Scriptures related to homosexuality, there are worse places to start than this book to get an overview. I can’t find myself jumping-up-and-down-excited about People to Be Loved, but I can affirm (sorry, couldn’t resist) it as a solid, useful volume.

Gentleness and Respect for all - addressing 'the transgender issue'

But in your hearts revere Christ as Lord. Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have. But do this with gentleness and respect, keeping a clear conscience, so that those who speak maliciously against your good behavior in Christ may be ashamed of their slander. For it is better, if it is God’s will, to suffer for doing good than for doing evil. -- 1 Pet 3:15-17, NIV

I promised myself and my readers not too long ago that my theo-rage-blogging days are over. Which means I’ve wrestled with myself now about whether or not to write this post. I’ve come down on the side, though, of writing it, because I think there’s something here to say that isn’t tied to any group or denomination or particular theological persuasion. So here goes.

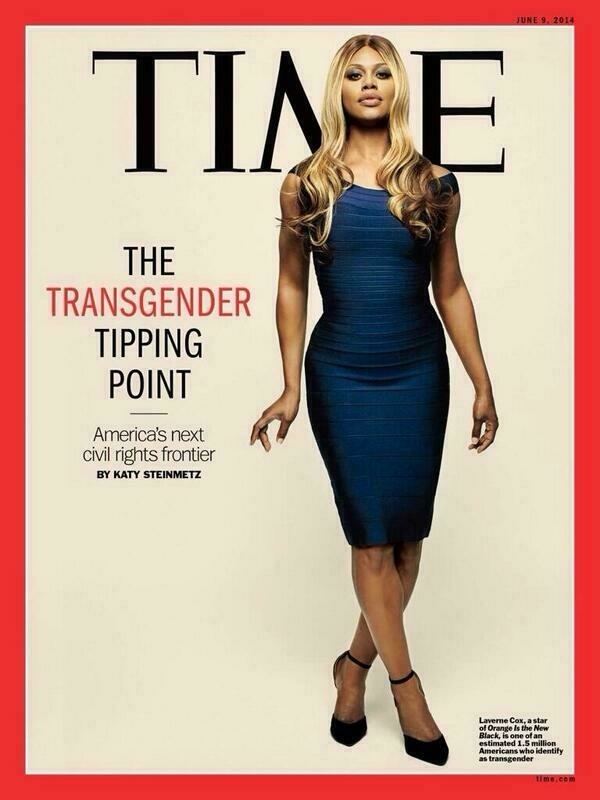

This is the cover of the latest issue of Time magazine. It features Laverne Cox, a transgender actress best known for starring in the Netflix series “Orange is the New Black”.

“The Transgender Tipping Point”, it declares. “America’s next civil rights frontier.”

I’m not a subscriber to Time, and haven’t been past a newsstand lately, so my first awareness of this cover came from a (re)tweet by Russell Moore (@drmoore) that looked like this:

https://twitter.com/drmoore/status/472105205211750400

Dr. Moore is President of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission, and a not-infrequent commentator on social and political topics. I don’t mean to call him out personally here; his attitude and commentary are likely no different than what I’d hear from many other corners of the evangelical church.

But I’m bothered by the approach. “Are you prepared for what’s next?” implies a significant level of us-against-them, fight-the-culture-war-to-win-it mentality that disrespects transgender people and doesn’t seem to recognize that they are cherished divine image-bearers just as much as we are.

I thought I was reading a little too much into it - afraid of my own biases, as it were - but then I read the stream of replies to Moore’s tweet. Those replies are even more disturbing. Referring to the actress as “it”, as a “fake ‘woman’”. Expressions of disgust ("…permanently lost my appetite.", “want to go into a bubble”). When one person refers to the actress as “her”, another one replies to ‘correct’ the first with “*his”.

To his credit, Dr. Moore’s follow-up tweet linked to a more nuanced position on ’the transgender issue’, as he puts it, which includes the declaration that “As conservative Christians, we do not see transgendered persons as “freaks” to be despised or ridiculed.” Later on he says that “…this also means that we will love and be patient with those who feel alienated from their created identities.”

One hopes that, on reflection, Dr. Moore and the folks who replied to him might recognize that those tweets have every likelihood of being interpreted as alienating and despising rather than loving and patient.

As Christians, we must do better.

In the verse I quoted at the top of this post, the Apostle Peter says that our testimonies of faith must be given with “gentleness and respect”, so that any accusations of bad behavior will be undeserved and slanderous.

I will be the first to admit that I don’t have a fully-formed theological position when it comes to transgender issues. This is a topic that will no doubt soon get fuller treatment in the theological world much as homosexuality has over the past decade.

But I do know this: as Christians we should cultivate an approach and reaction to all people that starts with love, care, and concern, not one of disgust and alienation. If we can’t even respect a person enough to address them by their preferred gender, how can we ever hope that they’ll listen to us long enough that we can tell them about God’s love for them?

“But we’re going to lose the culture war!”

Yeah, we are. We probably already have. We’re not called to win it. We’re called to be faithful. The Apostle Peter wasn’t ‘winning the culture war’ in his day, either. Which might be why he followed up the call to gentleness and respect with these words: “For it is better, if it is God’s will, to suffer for doing good than for doing evil.”

May that be the legacy of Christians in this place and time.

A few thoughts on the "yuck factor" discussion

In case you’re not already caught up: the discussion started with Thabiti Anyabwile’s post on TGC, “The Importance of Your Gag Reflex When Discussing Homosexuality and “Gay Marriage””. One-line summary: “Return the [gay marriage] discussion to sexual behavior in all its yuckiest gag-inducing truth.”

Then yesterday Richard Beck posted a response: On Love and the Yuck Factor. Two-line summary: (1) “I don’t think it’s healthy to use disgust to regulate moral behavior.” (2) “When disgust is involved any purported distinction being made between persons and behavior is… a verbal obfuscation of the underlying psychology.”

There have been a bunch of other thoughtful responses (to both men), including a long comment on Beck’s piece from “dmr5090” (sheesh, people, can’t you use real names at least?). Key points in those rebuttals to Beck have often been along the lines of (1) Shouldn’t sin gross us out?, (2) “Aren’t you just trying to argue that ‘homosexuality isn’t a sin’ without admitting it?” and (3) “The words ‘gag reflex’ and ‘yuck factor’ aren’t Anyabwile’s - he’s just quoting a gay journalist.”

To be fair, I have grossly simplified, hopefully not unfairly, all the posts I’ve linked so far. If you want to dig into this argument, go read them all.

So here’s the thing: I know there’s a battle raging among various flavors of Protestants and even evangelicals over homosexuality. But I can believe on one hand that homosexual acts are sinful, and on the other hand still respond with revulsion to Anyabwile’s post. Here’s why:

1. Inconsistent application of the tactic. Why do we not hear preachers like Anyabwile use this “gag reflex” topic when addressing other, more “acceptable” sins? Let’s hear a few sermons on gluttony that try to gross me out with discussions of sweaty mounds of obese flesh before you try to claim that the “gross out” strategy is really one you think should be used across the board.

2. The encouragement to revulsion at the act quickly leads to revulsion of the person. Yes, sin is revolting. All sin should be revolting to us. But to encourage a “gag reflex” response to homosexuality will very quickly lead a person to have that “gag reflex” toward the homosexual person. And that’s the furthest thing from what Christ calls us to. I know that Anyabwile says in his post that we “should not be mean and bigoted”. But I don’t understand how you can encourage a gag reflex when you hear “homosexual” and not end up that way. (Beck made this point in his post far better than I’m saying it here.)

(Observation: while writing this I was about to say that Anyabwile said we should still love the sinners, but he never actually says that in his piece. All he says is that we should not be mean and bigoted, and that we should ‘speak the truth in love’. And the truth, he says, is that homosexual relationships cannot properly be called ’love’. Not sure it’s fair to draw a conclusion from that, but it’s bothersome.)

3. This is the old “culture warrior” position again. Have we not learned yet that sin is not going to be defeated by us making the right arguments to those in privileged positions in the halls of power? Anyabwile seems to think that if he’d just managed to gross out the right people in powerful positions, we wouldn’t have legalized gay marriage. I say that’s baloney. We’ve had the evangelical attempts at political power for at least 30 years. Buchanan, Falwell, Dobson… How’s that worked out for us?

4. The Gospel is not “sin is icky”. The Gospel message is that we are all sinful, all equally in need of Christ’s grace and forgiveness. That God is in the process of making all things new, of drawing people to himself. That’s the message we need to be spending our time on.

What to do about "gay marriage", part 2

Becky observed last night that my post yesterday on gay marriage was rather wordy and not as simple as she would’ve liked. So, I’m taking that as a challenge, and today I’m going to try to condense my arguments a bit. Feel free to agree or disagree in the comments.

So, my list of assertions that lead my to my position on gay marriage:

1. While the Bible teaches that homosexual behavior is wrong, the Bible does not teach that the civil government should try to outlaw every sin.

Religious beliefs can disagree with government laws in one of three ways:

The law can require behavior that my religion tells me is a sin. For instance, pacifists who are drafted to serve in the military. Typically the US has allowed for conscientious objector status, allowing those people to take non-combat roles. Another example is the allowance in the Constitution to “affirm” rather than “swear” oaths of office, for those who believe they should not “swear”.

The law can outlaw a behavior that my religion tells me I must do. For instance, the law could instruct me not to share my faith with other people. In this case the Scriptures are quite clear - we must obey God rather than men. (Acts 5:29)

The law can allow a behavior that my religion says I must not do. And here the Scriptures are quieter. While certainly we know that God wants our rulers to be just and merciful, we don’t see anywhere that God says “your rulers should enact all of my laws as laws of the state.”

1 Tim 2:1-4 says this:

I urge, then, first of all, that requests, prayers, intercession and thanksgiving be made for everyone— for kings and all those in authority, that we may live peaceful and quiet lives in all godliness and holiness. This is good, and pleases God our Savior, who wants all men to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth.

Paul says that we pray for our rulers, with the goal or the hope being that we can live peaceful, quiet lives. And note that Paul doesn’t say to pray that our rulers would try to enforce God’s laws on everyone - Paul says to pray for peaceful, quiet lives, and that from that people might come to a knowledge of the truth.

2. If we’re not going to use Christian (or Muslim, or Jewish, etc) principles to dictate the details of our laws, instead we should base the laws on socially-agreed-upon principles of freedom, asking “what is good for society as a whole?”.

Because, really, what other platform are we going to use?

3. Socially-agreed-upon principles change over time.

Just one example out of many: when the USA was founded, the only people allowed to vote were white, land-owning males. This was the socially-accepted norm. Over the past two hundred years, society has come to agree that anyone 18 years of age or older, and who is not mentally incompetent, regardless of gender, race, or land, should be allowed the vote.

Those changes didn’t come about because either people said “oh my, our voting rules are un-Christian, we need to make them more Christian” or because people said “oh my, our voting rules are too Christian, we need to make them more secular”. By and large, the changes came about because society’s views, both Christian and secular, changed.

4. If you’re with me this far, then we’ve gotten to this question: is “gay marriage” a reasonable freedom to allow? Something that will be beneficial for, or at least not harmful to, society as a whole?

And this is where the debate really engages. My position is this: yes, gay marriage is a reasonable freedom to allow, for the following reasons:

- We can embrace a civil-religious disconnection.

- State-sanctioned marriage is essentially a specific path through contract law. When you get married, you automatically get a LOT of legal advantages, things that would be difficult to attain otherwise. What good reason do we have to say that any two people shouldn’t be allowed to enter into a contract that way?

- Society’s views have changed, and we may as well acknowledge the change rather than pretend it didn’t happen.

From a strictly pragmatic Christian viewpoint, too, we need to pick which battles we want to fight. Yes, we want to see each person come to know Christ and become more like Christ. By fighting this semantic argument over civil “marriage”, we aren’t accomplishing anything other than alienating a large group of people who Christ calls us to love. We certainly aren’t helping ourselves gain an audience with them so we can share the Gospel. Real change comes from the inside out, as the heart changes.

5. The government must protect the rights of private groups to discriminate based on their beliefs.

Freedom of association (guaranteed in the First Amendment) implies freedom of disassociation. If a church doesn’t want to perform gay marriages, they shouldn’t be required to. If the Boy Scouts don’t want to allow gays as leaders, they shouldn’t be required to. If a religious organization doesn’t want to hire gays, they shouldn’t be required to.

OK, so I cut it down to 5 points, albeit with a lot of bullets and lists in between. Questions? Comments? Snide remarks? Let it rip in the comments.

Recognizing the civil-religious disconnect, or, "what to do about 'gay marriage'"

I’ve been working through the whole ‘gay marriage’ issue in my head for a while now, driven in good part by the discussion over on rmfo.net (you’ve gotta be a member to read it, sorry) surrounding California’s Proposition 8. The evangelically-popular, Dobsonian position is familiar to me, but has always seemed (like most Dobsonian political positions) to be harmful to the Kingdom; focusing on divisive politics rather than loving everyone and focusing on the heart issues. Today, though, Andrew Sullivan’s piece on TheAtlantic.com really solidified things for me; in other words, he said what I’ve been thinking - only much more clearly and concisely.

For those of you who may be unfamiliar with Andrew Sullivan, here’s where he’s coming from: he’s a relatively conservative gay man. That in itself gives you some idea to which side of the debate he comes down on… but don’t let that bias you towards him without giving him a listen. He nails it.

[Many long for] a return to the days when civil marriage brought with it a whole bundle of collectively-shared, unchallenged, teleological, and largely Judeo-Christian, attributes. Civil marriage once reflected a great deal of cultural and religious assumptions: that women’s role was in the household, deferring to men; that marriage was about procreation, which could not be contracepted; that marriage was always and everywhere for life…

But that position, Sullivan says, is untenable.

If conservatism is to recover as a force in the modern world, the theocons and Christianists have to understand that their concept of a unified polis [(state)] with a telos [(purpose, goal)] guiding all of us to a theologically-understood social good is a non-starter. Modernity has smashed it into a million little pieces. Women will never return in their consciousness to the child-bearing subservience of the not-so-distant past. Gay people will never again internalize a sense of their own “objective disorder” to acquiesce to a civil regime where they are willingly second-class citizens. Straight men and women are never again going to avoid divorce to the degree our parents did. Nor are they going to have kids because contraception is illicit. The only way to force all these genies back into the bottle would require… [an] oppressive police state…

Exactly. My dad said much this same thing in a sermon he preached back before the election (which I still haven’t posted, sorry, Dad!) when he likened the Dobson-esque conservatives to the proverbial dog chasing a car. The problem for the dog is when it catches the car - what the heck do you do with it then?

Back to Mr. Sullivan:

That way is to agree that our civil order will mean less; that it will be a weaker set of more procedural agreements that try to avoid as much as possible deep statements about human nature. And that has a clear import for our current moment. The reason the marriage debate is so intense is because neither side seems able to accept that the word “marriage” requires a certain looseness of meaning if it is to remain as a universal, civil institution.

And then he nails it with an example that hadn’t occurred to me.

This is not that new. Catholics, for example, accept the word marriage to describe civil marriages that are second marriages, even though their own faith teaches them that those marriages don’t actually exist as such. But most Catholics are able to set theological beliefs to one side and accept a theological untruth as a civil fact. After all, a core, undebatable Catholic doctrine is that marriage is for life. Divorce is not the end of that marriage in the eyes of God. And yet Catholics can tolerate fellow citizens who are not Catholic calling their non-marriages marriages - because Catholics have already accepted a civil-religious distinction. They can wear both hats in the public square.

[Emphasis mine.]

I am convinced that this is the right position. Certainly, Christians need to be free to teach per their convictions on homosexuality, and need to be free to discriminate as to who they will marry, hire, and so on. (Sullivan argues specifically for those protections in his column.) But we need to accept, nay, support a broader, freer civil arrangement; an arrangement that allows for freedom for as many as possible to live as their conscience dictates in a way that is consistent with the peaceful, common good.

Putting that civil arrangement in place will provide a basis for the lively exchange of ideas that should be present in a free society. While it won’t look quite like what the Founders set up in the United State more than 200 years ago, it’ll be more what they intended. Let’s face it - we don’t live in 1780 anymore. We will do better if we adapt the principles of 1780 for the world of 2008 and move forward. For this topic that means embracing the civil/religious disconnect and supporting state-sanctioned civil marriage for both hetero- and homosexuals.