Category: Christianity

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

Asking the hard questions: not a crisis of faith, but rooted in faith

Later this year I’ll be teaching for 3 weeks at our church’s adult forum on the topic of Christian Universalism. In preparation I’m diving back in to some key books that have guided my path, starting with Thomas Talbott’s The Inescapable Love of God. It’s been a few years since I’ve read this one, but even before I get out of the first chapter I’m reminded why this one spoke to me so powerfully.

When wrestling with Augustine, Luther, and Calvin’s teaching on predestination and how it conflicted with what he had been raised to know of God’s love, he challenges the common “crisis of faith” framing:

In fact, what I have here called “a crisis of faith,” and at the time regarded as such, was not a crisis of faith at all. For it was precisely an unshakable faith in the love of God–a faith that my mother in particular had instilled within me–that made my doubts about Christianity and the Bible possible; and had I known more about the Bible at the time, or had I possessed a less naive view of revelation, I might have been spared these doubts as well.

This rings true to my own experience: that it was not a lack of faith that caused me to strike out in search of a more beautiful expression of God, but rather it was because of that faith that I knew there must be something better than what I was being taught. Hallelujah.

Richard Beck on loving Christianity (and really, loving certainty) more than loving Christ

It’s been a while since I’ve linked a Richard Beck post, but man oh man does he nail it today with his observations about young, aggressive converts to Orthodoxy and Catholicism. (I’d venture that in previous years we could’ve said this about “cage stage” Calvinist/Presbyterian converts, too.)

A lot of the negative and aggressive energy inserted into these debates is from men who have become recent converts to Orthodoxy. You might be aware of this trend and it’s impact upon Christian social media. The main take of these Orthodox converts is that every branch of Christianity, from Catholics to evangelicals, is a theological failure. Heretical, even. Only Orthodoxy preserves the one true faith.

This conceit, however, isn’t limited to the very online Orthodox. There are also aggressive Catholics who denigrate Protestantism. And in response to these Orthodox and Catholic attacks, there have arisen aggressive Protestant defenders.

Here’s my hot take. I think many of these loud and aggressive converts are more in love with Christianity than they are with Christ. They love the creeds, the church fathers, the liturgy, the saints, the history, the culture of Christendom, the doctrine, the dogma, the theology, the Tradition. What they don’t seem to love very much is Jesus, as evidenced in their becoming belligerent social media trolls.

But where does the vitriol come from? Beck says it’s “fear, plain and simple”. I think he’s right on this, too.

This is one reason we’re seeing so many young men gravitate away from evangelicalism toward Orthodoxy and Catholicism. As sola scriptura Protestants these young men were raised as epistemic foundationalists. In standing on Scripture they stood on a firm, solid, and unshakeable foundation of Truth. The Bible provided them with every answer to every question. Epistemically, they were bulletproof. They were right and everyone who disagreed with them was wrong. This certainty provided existential comfort and consolation. Dogmatism was a security blanket.

Then they went off to seminary or down some YouTube rabbit hole and discovered that “Scripture alone” was hermeneutical quicksand. Suddenly, the edifice of security began to crumble. Where to turn? Where to find a firm and unassailable foundation? The Tradition! One type of foundationalism (the Bible alone) was exchanged for another (the Tradition). In both cases, the evangelical need for bulletproof certainty remained a constant. There has to be some “correct” place to land in the ecclesial landscape. It’s utopianism in theological dress. But the underlying anxiety curdles the quest. Especially if, once the “one true church” is found, the old evangelical hostility and judgmentalism toward out-group members resurfaces. The underlying neurotic dynamic is carried over. Fundamentalism is merely rearranged. In order to feel secure and safe I need to scapegoat outsiders. Their damnation is proof of my salvation, their heresy confirms my orthodoxy.

Yes to all this. One of the big challenges I’ve found myself facing as I left evangelicalism and joined the Episcopal church is to be ok with the uncertainty; to accept that each tradition has its own foibles and messes. Another Beck post more than seven years ago prompted me to write (among other things) that even the most erudite theologian must be wrong on at least 5-10% of their theology. And if so, then certainty of “rightness” as the (usually unacknowledged) base of my security of salvation is inherently shaky ground.

All these years later I am more convinced than ever that the “conversion” I need isn’t from one denomination or tradition to another, but a conversion from a confidence rooted in my own belief’s rightness to a confidence rooted in God’s love for me and evidenced by my love for Jesus and my neighbor.

Characteristics of Spiritual Control

My therapist (himself an ordained minister) broadly sorts churches into two categories: churches whose functional goal is control of people, and churches whose goal is life enhancement. It’s a broad brush, open for nuance, and certainly one that many churches (especially ones my therapist would put in the control category) would dispute. But as broad categories I find them helpful to think through the impact of how a church’s teaching and culture actually affect people. Regardless of labels or stated purpose, a system’s designed purpose is, ultimately, what it produces. (In Jesus’ words: you will know them by their fruit.)

With that preamble, I’ve been reading Holy Hurt: Understanding Spiritual Trauma and the Process of Healing by Hillary L. McBride, PhD. I’m only about a quarter of the way in, but yesterday I ran into the chapter where she discusses the characteristics of an abusive spiritual environment, and… oof.

Here are some examples of how control is enacted.

Interpersonal or Social Control

- Cutting off relationship with others outside the group

- Limiting the kinds of information people have access to, especially if it challenges the thinking of or control/power held by the leaders

- Creating a strong in-group bias that renders those in the out-group as bad

- Creating demands on time and community commitments that limit contact with out-groups

Financial Control

- Requiring a portion of income to go to the religious group

- Expecting people to volunteer excessively, even if doing so negatively affects other areas of their lives

- Limiting women’s access to education or employment

- Guilting or pressuring individuals to give even more money to the community and suggesting that in return all their needs will be provided for (by God or by the community)

Physical and Behavioral Control

- Suppressing sexuality when not within the boundaries of heterosexual marriage

- Defining and policing expressions of sexuality in general

- Creating strict expectations about dress

- Creating moral superiority around categories of food and eating behaviors

- Holding expectations about leisure activities, including what can be read or watched, and shaming and devaluing behavior that is not “like the group”

Psychological Control

- Shaming and devaluing development of or connection to the self, and communicating that the self (and self-trust or knowing) is bad or sinful

- Forbidding critical thinking and encouraging self-policing of thoughts and emotions

- Suppressing of emotion outside worship experiences

- Praising blind faith while discouraging critical thinking or questioning

- Making decisions for individuals about career choices, dating and marriage, or hobbies/giftings

- Requiring giving authority for one’s life to the leaders

- Promoting black-and-white thinking

When I compare those to my religious upbringing and adult life in conservative evangelical Christianity, by my count I have experienced at least 19 out of 20. And was taught that this was normal and good.

I’ve still got a lot of unpacking to do.

The lectionary readings were just some real bangers today

When the Lectionary readings seem ever so timely… First up, from Jeremiah 23:

I have heard what the prophets have said who prophesy lies in my name, saying, “I have dreamed, I have dreamed!” How long? Will the hearts of the prophets ever turn back—those who prophesy lies, and who prophesy the deceit of their own heart? They plan to make my people forget my name by their dreams that they tell one another, just as their ancestors forgot my name for Baal. Let the prophet who has a dream tell the dream, but let the one who has my word speak my word faithfully.

Substitute “American evangelical preachers” here for “the prophets” and the word still burns with fire.

Then comes Psalm 82, which includes:

Save the weak and the orphan;

defend the humble and needy;

Rescue the weak and the poor;

deliver them from the power of the wicked.

So say we all.

The ‘great cloud of witnesses’ reading from Hebrews is a banger on its own - mocking, flogging, frigging sawn in two, but the bit that stuck out at me this morning was this verse, right before the big “therefore”:

Yet all these, though they were commended for their faith, did not receive what was promised, since God had provided something better so that they would not, apart from us, be made perfect.

So all these heroes of the faith still did not get everything that was promised. “WTF?” the reader may rightly ask. Why not?

Because, the author of Hebrews says, they need all of us with them to be complete, to reach fulness. Wowza.

And then there’s the Gospel

I will quote it in full (from Luke 12):

Jesus said, “I came to bring fire to the earth, and how I wish it were already kindled! I have a baptism with which to be baptized, and what stress I am under until it is completed! Do you think that I have come to bring peace to the earth? No, I tell you, but rather division! From now on five in one household will be divided, three against two and two against three; they will be divided: father against son and son against father, mother against daughter and daughter against mother, mother-in-law against her daughter-in-law and daughter-in-law against mother-in-law.”

He also said to the crowds, “When you see a cloud rising in the west, you immediately say, ‘It is going to rain’; and so it happens. And when you see the south wind blowing, you say, ‘There will be scorching heat’; and it happens. You hypocrites! You know how to interpret the appearance of earth and sky, but why do you not know how to interpret the present time?”

Our priest this morning called to note the specific generational nature of the conflict that Jesus brings. And which among us has not felt that conflict this past decade? So many of us had and continue to have painful disagreements with parents about what it looks like to follow Jesus. We can read the clouds and see the storm brewing. We’re already feeling the wind gusts. We need to buckle in and hold tight. This may well be the time when we make up what is lacking in Christ’s suffering, as we build toward the completeness of the faithfulness of the people of God.

A fresh perspective on Romans 8:28

In the journey of deconstructing my evangelical faith, it’s astonishing how many times a better reading of a Biblical text is right there just waiting to be embraced once someone points it out. And it’s so refreshing to realize that this can mean you don’t have to discard the Biblical text to hold a different viewpoint - you only have to be willing to think about another possible interpretation.

This morning’s example comes from Brad Jersak’s latest newsletter where he answers the question “Does Romans 8:28 teach that God is in control?”

We know that all things work together for good for those who love God, who are called according to his purpose. (Rom. 8:28, NRSV)

As an evangelical, Romans 8:28 was trotted out as a sort of determinist get-out-of-jail-free card to deal with theodicy. “If we have an omnipotent, omniscient God”, one might reasonably ask, “why do bad things happen to good/innocent people?” “Well, we can’t know”, comes the answer, “but we can trust that Romans 8:28 is true and that God is orchestrating behind the scenes somehow for our good.”

It’s an unsatisfying answer, one that manipulates the recipient into blind acceptance of the evil circumstance and shames them for a lack of faith if they despair in it. But the words are right there. What else could they possibly mean?

Oh, blessed context

Rather than cherry pick this single verse, says Jersak, let’s look at the flow of the whole chapter.

Romans 8 tells us that all of creation is groaning under the catastrophe of human sin. And when the love of God fills our hearts, we begin to mourn too. We don’t even know how to pray. But the Holy Spirit in us cries out with ‘groans too deep for words’ and ‘we cry, ABBA!’ It appears that all is lost. It seems like evil reigns and death has defeated us.

Then he quotes verses 19-23:

19 For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God; 20 for the creation was subjected to futility, not of its own will but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope 21 that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. 22 We know that the whole creation has been groaning in labour pains until now; 23 and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly while we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies.

Then he interprets:

Creation is groaning and waiting for God’s children to ‘be revealed’ or ‘manifest’ – to ‘show up’ and participate in ‘your kingdom come, your will be done on earth as it is in heaven.’ It’s waiting for us to step into our calling now through the labor pains of history, even as we await our final resurrection. The wholeness and freedom of eternity that we await begins now as healing and redemption. Here. In this life.

Even before we get to v. 28, I find this such a helpful interpretation of v. 19-23. Verse 19 in particular was always opaque to me - what event of “revelation” is creation waiting for? Something eschatological? But no, this reading is much more sensible: creation is waiting to see which people will be revealed to be the children of God by how they go about doing God’s work of healing and redemption. Yes.

Then we get to v. 28. Back to Jersak [bold emphasis mine]:

“All things work together” is NOT “everything works out.” Rather, “all things” refers to the whole of creation that is groaning and waiting for us. When we, as Christ’s royal priesthood, step into our vocation, we will discover “all things working together” – cooperating, participating, serving with us in the cause of redemption. We can’t manipulate (force, control) our circumstances to serve our ends. But when we live as God’s beloved children, serving divine love in this world, it’s amazing how ‘all things’ start diving in to help.

I love this so much. That v. 28 isn’t a call to just shut up and try to trust that God is magically working things out in unseen ways. Rather, it’s a call to start God’s work as God’s representatives here in the world, with the encouragement that the rest of creation will be working with us toward ultimate reconciliation and redemption.

That’s a beautiful, hopeful picture that both encourages and motivates me when I consider all our current groaning and waiting.

Something has happened that makes the entire process of self-justification irrelevant

I’m reading Rowan Williams’ Where God Happens: Discovering Christ in One Another, and this bit is just beautiful:

The church is a community that exists because something has happened that makes the entire process of self-justification irrelevant. God’s truth and mercy have appeared in concrete form in Jesus and, in his death and resurrection, have worked the transformation that only God can perform, told us what only God can tell us: that he has already dealt with the dreaded consequences of our failure, so that we need not labor anxiously to save ourselves and put ourselves right with God.

The church’s rationale is to be a community that demonstrates this decisive transformation as really experienceable. And since one of the chief sources of the anxiety from which the gospel delivers us is the need to protect our picture of ourselves as right and good, one of the most obvious characteristics of the church ought to be a willingness to abandon anything like competitive virtue (or competitive suffering or competitive victimage, competitive tolerance or competitive intolerance or whatever).”

American culture: a 'negative world' for Christianity?

My friend Charles pointed me to an NYT profile of Aaron Renn, a businessman from Indiana who gained attention for framing current American culture as being hostile to conservative Christianity, a “negative world” that developed somewhere around 2016.

Renn lives in Carmel, Indiana, a city he describes as proof that “we can have an America where things still work”. Ruth Graham, the author of the profile, compares it to Mayberry or Bedford Falls. The references seem clear enough: this idyllic community hearkens back to 1950s white middle-class America, a golden age in the minds of conservative Christianity. (Less of a golden age for, say, African Americans.) Carmel is an 80% white suburb in the middle of the 70% white Indianapolis metropolitan area. 95% of its residents are US Citizens. Renn describes this environment as “diversity that works”.

Why 2015?

As a child of evangelicalism who grew up in the 1980s and 1990s hearing that the culture was evil, biased against Christians, and an appropriate target for boycotts and hate, it surprised me that Renn’s viral idea was that the “positive world” phase of America lasted until 1994, and the “neutral world” lasted until 2015. What, in this version of history, was the magic event in 2015 that suddenly made America a negative place for Christians? Oh, of course: Obergefell. Because while Mayberry and Bedford Falls may have had a token minority from time to time, they for sure didn’t have any gay folks.

I have some questions.

The unstated assumptions in Renn’s view are begging to be examined. Is it good for Christians to be the dominant culture and dominant in politics? Does that make for a healthy, Jesus-like faith? Why does a Christian position need to be actively opposed to gay marriage? Why can’t Christians simply live with tolerance of their gay neighbors?

I suspect that Renn’s personal beliefs may be more interesting than the profile lets on. He seems very fond of nice public infrastructure and public funding for special education programs - things that are quite unpopular in the current conservative movement.

It’s not clear from this profile where Renn’s theological sympathies lie. Culturally he seems to be wishing for an Eden free not just from gays but also from boorishness, gambling, legalized drugs, and tattoos. Those issues don’t appeal widely enough to gather steam as a movement. But evangelical Christianity is apparently quick to latch on to the trinity of “sex, gender and race” as touchstones of a “secular orthodoxy” that make America a negative place for Christians.

The theologians quoted in the profile come largely from the neo-Reformed movement. Renn apparently got really into Tim Keller for a while, but concluded that Keller’s approach to culture is “insufficient” for the “negative world”. So now he wants to get more aggressive, pursuing societal and political power in a move he likens to the Hebrews conquering Canaan. It should come as no surprise, then, that Josh McPherson is the first pastor quoted in this profile. McPherson, who is hosting a podcast series to help pastors to minister in Renn’s “negative world”, was a primary disciple of Mark Driscoll, the pugilistic, misogynist church planter from Seattle who preached a gospel of (tattooed) hyper-manliness before eventually blowing up his church in scandal and eventually reemerging as a MAGA Pentecostal in Arizona.

It doesn’t add up.

I wish that Graham’s profile had dug further into some of Renn’s inconsistencies. Consider his opinions on his local town:

Carmel is thriving, in Mr. Renn’s view, because its Republican leaders have focused on things like public safety, low taxes, and excellent infrastructure and amenities, while avoiding the distractions of what he called “extreme ideologies,” like D.E.I. hiring practices or banning gasoline-powered lawn equipment.

How in the world do “excellent infrastructure and amenities” and robust public education (from which Renn’s son benefits) align with the current conservative push to get rid of as much government as possible?

And if I’d had any hair left to pull out, I would’ve lost it at this paragraph:

It is a familiar theme: Things may be bad, but liberals started it. The election of Mr. Trump as president is only possible in “negative world”, Mr. Renn said. In “positive world”, an extramarital affair tanked Gary Hart’s presidential campaign. In “neutral world”, Bill Clinton was damaged by his infidelity but survived politically. In “negative world”, with the safeguards of “Christian moral norms” out the window, it was too late for liberals to make any coherent critique of Mr. Trump’s open licentiousness.

On one hand, his point about the relative political damage of marital infidelity has decreased over the decades. But let’s stop and remember for a moment that Gary Hart and Bill Clinton were attacked by conservative Christian Republicans, claiming moral outrage against the infidelity. Why is it suddenly incumbent on the liberals to muster the moral outrage against Donald Trump?

There is no Mayberry to go back to.

Renn sure seems to want to return to his “positive world”, a utopia where you marry a nice church girl, have 2.5 kids and send them to school on their bikes down perfect sidewalks and trails past manicured lawns and picket fences, but where you don’t have to pay taxes to provide those amenities. A community that’s predominantly white, straight, and Christian, with a few token minorities to let you feel diverse and tolerant, and even fewer gays because you’ve run them off so you can feel righteous.

Just one problem: this utopia has never existed. And in the brief slice of 1950s America that Renn idealizes, the white Christian middle-class paradise was built on the backs of the poor, the minorities, and 95% marginal income tax rates for the wealthy.

Where is Jesus?

Notably absent from Renn’s arguments: any hint of concern about being like Jesus. Renn’s ideal apparently isn’t found in the Beatitudes, the Sermon on the Mount, or the Good Samaritan; rather it’s in Mayberry.

But a Christianity void of Jesus is no more than a moralistic shell designed to reclaim a bygone cultural hegemony. Indeed, the most Jesus-like perspective in the whole piece comes from a Muslim commentator:

…as a member of a religious minority for whom the United States has never been “positive world”, Muslim commentator Haroon Moghul said he did not see neutral- or negative-world occupancy as catastrophic.

“Just because wider society isn’t embracing me or rejoicing over me doesn’t mean I get to lash out in response,” he said. “The culture may be opposed to you, but that doesn’t mean you’re not legally and politically secure.”

Ironically, the new Christian hegemony forming under Donald Trump, praised by Renn, is working to ensure that those whom their culture opposes are in fact not legally or politically secure. Or even financially or physically secure.

I am wearily reminded of the trendy evangelical question from my youth: what would Jesus do?

Faith is more about longing and thirsting than knowing and possessing

David Brooks has a lovely essay published in the New York Times yesterday on his journey from agnosticism into faith. It came not, he says, through some academic study or intellectual enlightenment, but through experiences in life.

When faith finally tiptoed into my life it didn’t come through information or persuasion but, at least at first, through numinous experiences…. In those moments, you have a sense that you are in the presence of something overwhelming, mysterious. Time is suspended or at least blurs. One is enveloped by an enormous bliss.

He describes occasions, literally from the mountain top to underground (the New York subway) where unusually beautiful and real things broke through into his awareness, changing his perspective on reality.

That contact with radical goodness, that glimpse into the hidden reality of things, didn’t give me new ideas; it made real an ancient truth that had lain unbidden at the depth of my consciousness. We are embraced by a moral order. What we call good and evil are not just preferences that this or that set of individuals invent according to their tastes. Rather, slavery, cruelty and rape are wrong at all times and in all places, because they are an assault on something that is sacred in all times and places, human dignity. Contrariwise, self-sacrificial love, generosity, mercy and justice are not just pleasant to see. They are fixed spots on an eternal compass, things you can orient your life toward.

This process took time, Brooks says, describing it as less a “conversion” than an “inspiration”, where new life was breathed into things he had already intellectually known for a long time. And it results in something that is less a concrete certainty than a new longing:

The most surprising thing I’ve learned since then is that “faith” is the wrong word for faith as I experience it. The word “faith” implies possession of something, whereas I experience faith as a yearning for something beautiful that I can sense but not fully grasp. For me faith is more about longing and thirsting than knowing and possessing.

And in a paragraph that would make Jamie Smith smile, Brooks observes that what you desire shapes who you are becoming.

It turns out the experience of desire is shaped by the object of your desire. If you desire money, your desire will always seem pinched, and if you desire fame, your desire will always be desperate. But if the object of your desire is generosity itself, then your desire for it will open up new dimensions of existence you had never perceived before, for example, the presence in our world of an energy force called grace.

There’s so much goodness in this essay that I could quote the whole thing but really just recommend you go read it. This gift link) gives you the full article even if you’re not an NYT subscriber. It’s such a delight to hear someone talk so freely and publicly about their faith journey.

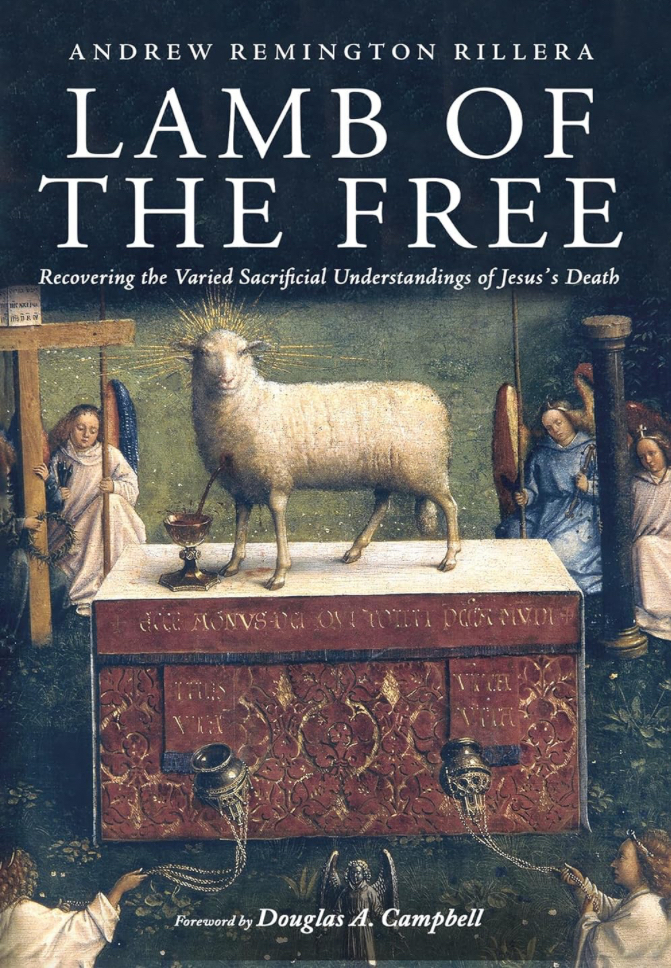

Lamb of the Free by Andrew Remington Rillera

I have a small handful of theological books in my past that I look back on as turning points - books that spoke to me at my particular place and time, opened my eyes, and set my thinking about God in a new direction. The first of those is NT Wright’s Surprised By Hope; the second is Ilia Delio’s The Unbearable Wholeness of Being. I’ll give it a week or two before I inscribe this in stone, but I’m inclined to think that Andrew Rillera’s Lamb of the Free is the next one. Let me try to explain.

In the Protestant church (at least), there has been much ink spilled over the years to systematize atonement theories, that is, to organize all the teaching about Jesus’ death and how it works to save us into some sort of coherent, synthesized framework. In the conservative evangelical world of my first 40 years as a Christian, the predominant, nay, the only acceptable atonement theory is penal substitutionary atonement, usually abbreviated PSA. PSA says that each of us, as a sinner, deserve God’s punishment, but that Jesus died in our place, taking that wrath upon himself. The children’s bibles usually summarize it as “Jesus died so I don’t have to”.

Rillera says that PSA fails to pay attention to how sacrifices worked in the Old Testament, and as such then horribly misreads the New Testament (particularly Paul and Hebrews). This may be the book that inspires me to go back to where I always get bogged down in the Bible In A Year reading plans, and do a close reading of Leviticus.

Rillera starts right off the bat in chapter 1 by making the assertion that

There is no such thing as a substitutionary death sacrifice in the Torah.

He notes that “for sins that called for capital punishment, of for the sinner to be “cut off”, there is no sacrifice that can be made to rectify the situation”, and that far from animal blood on the altar being a substitute for human blood, human blood actually defiled the altar rather than purifying it. Neither was that animal sacrifice about the animal suffering; to maltreat the animal “would be to render it ineligible to be offered to God”, no longer being “without blemish”. Already you can see the distinctions being drawn between this close reading of Levitical sacrifices and the usual broad arguments made in favor of PSA.

Lamb of the Free takes 4 chapters - a full 150 pages - to review OT sacrifices. I’m not going to try to summarize it here. But I have a new understanding and appreciation for paying attention to those details now! Then in chapter 5 he turns the corner to talk about Jesus, and summarizes his arguments thusly:

(1) According to the Gospels, Jesus’s life and ministry operated entirely consistent with and within OT purity laws and concern for the sanctuary.

(2) Jesus was a source of contagious holiness that nullified the sources of the major ritual impurities as well as moral impurity.

(3) Thus, Jesus was not anti-purity and he was not rejecting the temple per se.

(4) Jesus’ appropriation of the prophetic critique of sacrifice fits entirely within the framework of the grave consequences of moral impurity. That is, like the prophets, Jesus is not critiquing sacrifice per se, but rather moral impurity, which will cause another exile and the destruction of the sanctuary.

(5) But, his followers will be able to experience the moral purification he offers.

(6)The only sacrificial interpretation of Jesus’s death that is attributed to Jesus himself occurs at the Lord’s Supper. At this meal Jesus combines two communal well-being sacrifices… to explain the importance of his death. However, the notion of kipper [atonement] is not used in any of these accounts…

There’s a lot there, and Rillera unpacks it through the second half of the book. (I was particularly enthusiastic at his point (2), as it dovetails neatly with Richard Beck’s Unclean, where Beck argues that Jesus’ holiness was of such a quality that indeed, sin didn’t stick to him, but rather his holiness “stuck to”, and purified, other people’s sin and sickness.) Rillera says that Jesus’ death conquered death because even death was transformed by Jesus’ touch, and that Jesus came and died not as a substitution but rather as a peace offering from God to humankind. (His unpacking of Romans 3:25-26 and the word hilastērion was particularly wonderful here.) Jesus’ suffering under sin and death was in solidarity with humankind, and uniquely served to ultimately purify humankind from death and sin. (Really, I’m trying to write a single blog post here and summarize a 300 page book. If you’ve gotten this far and you’re still interested, go buy the book and read it. If you want to read it but it’s too pricy for you, let me know and I’ll send you a copy. I’m serious.)

I’ll wrap this up with a beautiful paragraph from a chapter near the end titled “When Jesus’s Death is Not a Sacrifice”. In examining 1 Peter 2, Rillera says this:

First Peter says that Jesus dies as an “example so that you should follow his steps”. In short, Jesus’s death is a participatory reality; it is something we are called to follow and share in experientially ourselves. The logic is not: Jesus died so I don’t have to. It is: Jesus died (redeeming us from slavery and forming us into a kingdom of priests in 2:5, 9) so that we, together, can follow in his steps and die with him and like him; the just for the unjust (3:18) and trusting in a God who judges justly (2:23; 4:19). This is what it means to “suffer…for being a ‘Christian’” (4:15-16). It does not particularly matter why a Christ-follower is suffering or being persecuted; it only matters that they bear the injustice of the world in a Christ-like, and therefore, a Servant-like manner.

There are a dozen other bits I’d love to share - maybe in another post soon. But for now, I’m thankful for Andrew Remington Rillera and his wonderful work in Lamb of the Free. I’ll be thinking about this for a long time.

A couple recommended reads: Trusting your Heart, and Christianity as an MLM

A couple posts came through my inbox while I was traveling the last few days which I want to pass on and feel like they have some parallels:

Katelyn Beaty asks “What if you can trust your heart?”

I have written before about evangelicals’ love for playing the Jeremiah 17:9 card. This tactic is regularly used to push people into submission to their leaders’ arguments even when their internal compass says something isn’t right. Beaty calls out this unease with feelings so prevalent in Reformed evangelicalism, and says we need to pay attention to our whole selves, our gut instinct as well as our rational thought.

…I’ve only grown in the belief that our gut is always speaking and deserves to be listened to. “Gut intuition” is distinct from emotions more broadly. But both are pre-rational, something we feel in our bodies before we have the words to articulate them. And I wonder if that’s why a lot of the evangelical world has trouble honoring them: we’ve inherited a mind-body dualism that says that mind is good and the body is bad. And, of course, that the body is the realm of women: messy, “irrational,” “crazy,” prone to quick changes and fluctuations, etc. This is all Plato, not Jesus, folks…

I can’t tell you the number of stories I’ve heard that someone’s “off” feeling about a person, place, or institution proved to be disastrously true, that they should have spoken up sooner but stuffed their feelings in the name of loyalty to a leader or cause. And I wonder if we’d have fewer church scandals if Christians honored intuition as a worthy source of truth — even as a place where the Holy Spirit is speaking to or through us, if only we would listen.

I think she’s onto something there.

Second is Katharine Strange’s post on ‘Christianity vs. Therapy’. In reviewing Anna Gazmarian’s Devout: A Memoir of Doubt, Strange discusses evangelicalism’s long-standing beef with psychology and therapists. Many evangelical churches are strong on Biblical Counseling, a movement which trains laypeople to exclusively use Scripture to counsel people, a movement which is strongly antagonistic to professional psychotherapy. (Oh, do I have thoughts on this. But I’ll save them for another post.)

Strange pulls at another thread in suggesting why evangelicalism is so opposed to therapy, and it resonates with my own experience:

But I think a large part of the problem boils down to the way that Christianity is “sold” in this country. As I’ve written about before, there’s so much pressure to convert our friends and neighbors that what we often end up presenting to the world is a kind of “prosperity gospel lite”—Jesus as cure-all. Being both Christian AND a person with problems is bad for the brand.

This “multi-level marketing” version of Christianity leads to a religion that values a mask of perfection over authenticity. Belonging, in this case, means cutting off parts of ourselves, whether that’s our sexuality/gender expression, our personal struggles, or even the fact that we experience basic feelings like sadness, irritation, envy, etc. It’s toxic positivity as a ticket to sainthood. Churches that buy into this methodology create lonely people even in the midst of community (for what is belonging without authenticity?) They also have a tendency to thrust narcissistic and authoritarian types into leadership because these are precisely the kind of people who are best at never letting the mask slip. Such environments can easily erupt into abuse, religious trauma, perfectionism, and scrupulosity.

While I knew MLMs were largely fueled and run by religious people, I hadn’t ever really thought about the idea that evangelicalism is essentially selling Christianity as a sort of MLM, by MLM principles. Now I can’t unsee it.