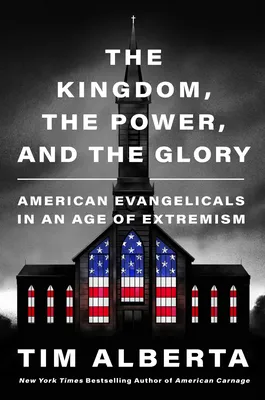

Recommended Reading: The Kingdom, The Power, and The Glory by Tim Alberta

My first completed book of the year is one I can wholeheartedly recommend: The Kingdom, The Power, and The Glory by Tim Alberta. Subtitled “American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism”, journalist Alberta’s book details his many interviews with American Evangelical leaders since the rise of Trump in 2016. He interrogates their motivations, how their words align with their actions, and how those words and actions comport with the teachings of Jesus.

Alberta is uniquely positioned to write a book like this. A professional journalist currently with The Atlantic, he has also written for, among others, Politico and The Wall Street Journal. But, as he reveals in the book’s initial chapters, he is also a pastor’s kid. His father, up until his untimely death, was the pastor of a large Evangelical Presbyterian church in Michigan. Alberta grew up a devoted Christian within that church, and continues today as a professing Christian. The Kingdom, The Power, and The Glory at places verges on memoir. But Alberta’s fluency with evangelical language, teaching, and culture give him an insight and authority that other journalists would lack.

If you have been following along in the Evangelical culture wars post-2016, most of the folks Alberta discusses will be familiar. He introduces them chapter by chapter: The Falwells and Liberty University, Robert Jeffress, and the Southern Baptist Convention. Firebrands like Greg Locke. Unabashed politicos like Ralph Reed. Fradulent historian David Barton. SBC stalwart-turned-outcast Russell Moore. Journalist Julie Roys. Pastor Brian Zahnd as a Midwestern prosperity preacher turned lonely prophet.

Whether it’s on purpose or just so close to home (for both the author and me) that Alberta couldn’t avoid it, the theme of children of Evangelicals turning and becoming their parents’ reproof played over and over through the book. Nick Olson, the son of an early Liberty student who came back to teach, only to be driven away when his politics didn’t align. Rachael Denhollender, the conservative homeschooled gymnast who, after bravely testifying against her abuser, became an advocate for sexual abuse victims within her own denomination. Cameron Strang, CEO of Relevant magazine, the son of a religious huckster. Jonathan Falwell, at a crossroads after taking over leadership of the “family business”, Liberty University. Alberta finally questions his own actions and motivations. Would he have been willing to ask these questions, to write this book, were his father still alive and in the pastorate? That question remains forever unknown. I understand, at least a little bit, Alberta’s quandary.

Over the past decade a pattern has emerged for me. When I encounter someone from my generation, usually online, who speaks with a resonant voice of sanity about America’s religion and politics, it turns out they, like me, grew up evangelical, usually homeschooled, and have spent their adult lives forging a path out. I’m thinking of people like author Lyz Lenz, new NYT film critic Alissa Wilkinson, writer and editor (and Alissa’s former podcast-hosting sidekick) Sam Thielman, NPR journalist Sarah McCammon, and famous lawyer spouse Jacob Denhollander, kindred spirits all. I’m now going to add Tim Alberta to that list.

At the end of the book, Alberta expresses an uncertain hope that this younger generation is successfully turning the evangelical world away from the worst of its political debauchery. To my mind, that jury is still out. Leader after leader throughout the book express their befuddlement and confusion as to why so much of the Evangelical church has been willing to follow political prophets away from the call of Jesus. Like them, Alberta doesn’t have the answer. But with this book, he has done what he can: incontrovertably documenting the political corruption of the American Evangelical church for anyone willing to read it.