A Serious Argument over a Traffic Stop, or, Why I Love Reading Supreme Court Decisions

One of my secret guilty pleasures (and here you get to plumb the depths of my weird mind) is reading Supreme Court opinions. (I enjoy listening to recordings of the oral arguments, too, but they can get rather dull at times.) I’ve had a fascination with the legal system and particularly the US Supreme Court since I was in high school. I contemplated taking up law as a career path before studying engineering instead, but law continues to fascinate me.

The beauty of the Supreme Court is that by a time a case gets to that level, they’re not dealing with run-of-the-mill principles or with trying to establish facts. The facts have already been established by lower courts, the principles already argued back and forth a couple times in appeals; the USSC only takes on the case when there’s a novel principle to be decided, and when that happens, some of the top legal minds in the country get together to argue the merits.

The thing I enjoy about USSC opinions is that they’re scholarly and dense without being utterly incomprehensible. I’m no legal scholar and undoubtedly don’t get all the case references, but I can sit and read through a 10-page opinion and pretty much understand the gist of the argument, think it over myself, and try to decide which side of the opinion I’d come down on. And sometimes the Justices really get fired up with an opinion, and then the reading gets fun.

But this shouldn’t all be abstract - here’s a recent example.

Navarette v. California

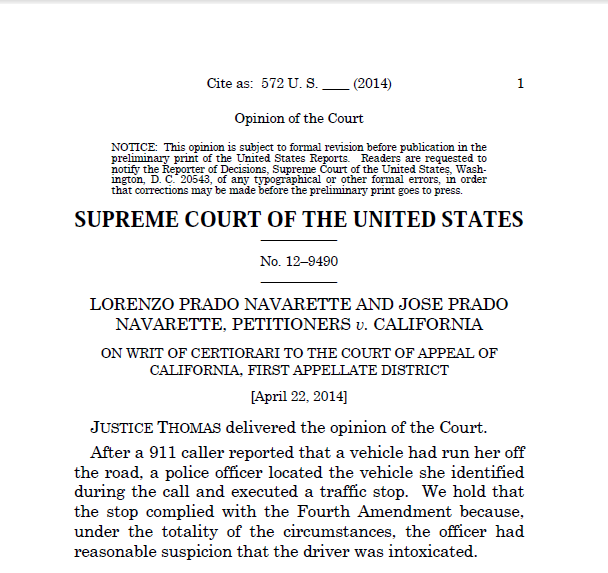

Navarette v. California was argued before the Court on January 21, 2014, and the decision and opinions were published April 22 (today as I’m writing this). The case summary and opinions are available on the USSC website, and the headnote for the decision provides a nice summary of the case:

A California Highway Patrol officer stopped the pickup truck occupied by petitioners because it matched the description of a vehicle that a 911 caller had recently reported as having run her off the road. As he and a second officer approached the truck, they smelled marijuana. They searched the truck’s bed, found 30 pounds of marijuana, and arrested petitioners. Petitioners moved to suppress the evidence, arguing that the traffic stop violated the Fourth Amendment. Their motion was denied, and they pleaded guilty to transporting marijuana. The California Court of Appeal affirmed, concluding that the officer had reasonable suspicion to conduct an investigative stop.

So did you get that? We’re arguing here over whether the police had a reasonable suspicion to make a traffic stop and conduct a search. The word “reasonable” is key here, since the 4th Amendment to the US Constitution says, in part, “The right of the people to be secure… against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated…”.

In this particular case, an anonymous 911 caller claimed that a truck “ran the [caller] off the roadway” and reported the truck’s make, model, and license plate number, suggesting that the driver might be drunk. The highway patrol found the truck, followed it for 5 minutes, didn’t see any additional erratic driving behavior, but stopped the truck anyway. When they approached the truck, they smelled marijuana, performed a search, found a bunch of it, and made an arrest.

So there’s the question. Does the Fourth Amendment require an officer who received information regarding drunken or reckless driving to independently corroborate the behavior before stopping the vehicle?

Today the US Supreme Court decided that the answer is yesno. [Whoopsie there! Thanks to _steve in the comment below for correcting me.] Justice Clarence Thomas wrote the majority opinion, which was joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Alito, Kennedy, and Breyer. That opinion runs from page 3 through page 13 of the decision PDF, and it’s not incredibly dense. (It’s also in a narrow-width column so it’s not as long as it sounds.)

Here’s the summary paragraph of the decision:

Like White, this is a “close case.” 496 U. S., at 332. As in that case, the indicia of the 911 caller’s reliability here are stronger than those in J. L. 2, where we held that a bare-bones tip was unreliable. 529 U. S., at 271. Although the indicia present here are different from those we found sufficient in White, there is more than one way to demonstrate “a particularized and objective basis for suspecting the particular person stopped of criminal activity.” Cortez, 449 U. S., at 417–418. Under the totality of the circumstances, we find the indicia of reliability in this case sufficient to provide the officer with reasonable suspicion that the driver of the reported vehicle had run another vehicle off the road. That made it reasonable under the circumstances for the officer to execute a traffic stop. We accordingly affirm.

So that’s not too awful or confusing, right?

Then the fun begins, because you have a dissenting opinion written by arch-conservative Justice Scalia which is joined by the three most liberal members of the court, Justices Ginsburg, Kagan, and Sotomayor. And Scalia, when he gets a little bit wound up, can be entertaining. This one is a prime example.

Here’s how he starts:

Today’s opinion does not explicitly adopt such a departure from our normal Fourth Amendmentrequirement that anonymous tips must be corroborated; it purports to adhere to our prior cases, such as Florida v. J. L., 529 U. S. 266 (2000), and Alabama v. White, 496 U. S. 325 (1990). Be not deceived. Law enforcement agencies follow closely our judgments on matters such as this, and they will identify at once our new rule: So long as the caller identifies where the car is, anonymous claims of a single instance of possibly careless or reckless driving, called in to 911, will support a traffic stop. This is not my concept, and I am sure would not be the Framers’, of a people secure from unreasonable searches and seizures.

Then he starts busting on the arguments.

All that has been said up to now assumes that the anonymous caller made, at least in effect, an accusation of drunken driving. But in fact she did not. She said that the petitioners’ truck “‘[r]an [me] off the roadway.’”.. That neither asserts that the driver was drunk nor even raises the likelihood that the driver was drunk. The most it conveys is that the truck did some apparently nontypical thing that forced the tipster off the roadway, whether partly or fully, temporarily or permanently. Who really knows what (if anything) happened? The truck might have swerved to avoid an animal, a pothole, or a jaywalking pedestrian. But let us assume the worst of the many possibilities: that it was a careless, reckless, or even intentional maneuver that forced the tipster off the road. Lorenzo might have been distracted by his use of a hands-free cell phone… or distracted by an intense sports argument with José… Or, indeed, he might have intentionally forced the tipster off the road because of some personal animus, or hostility to her “Make Love, Not War” bumper sticker. I fail to see how reasonable suspicion of a discrete instance of irregular or hazardous driving generates a reasonable suspicion of ongoing intoxicated driving. What proportion of the hundreds of thousands—perhaps millions—of careless, reckless, or intentional traffic violations committed each day is attributable to drunken drivers? I say 0.1 percent. I have no basis for that except my own guesswork. But unless the Court has some basis in reality to believe that the proportion is many orders of magnitude above that—say 1 in 10 or at least 1 in 20—it has no grounds for its unsupported assertion that the tipster’s report in this case gave rise to a reasonable suspicion of drunken driving.

That’s the USSC version of a smackdown, right there. But he’s not done!

That the officers witnessed nary a minor traffic violation nor any other “sound indici[um] of drunk driving,”… strongly suggests that the suspected crime was not occurring after all. The tip’s implication of continuing criminality, already weak, grew even weaker. Resisting this line of reasoning, the Court curiously asserts that, since drunk drivers who see marked squad cars in their rearview mirrors may evade detection simply by driving “more careful[ly],” the “absence of additional suspicious conduct” is “hardly surprising” and thus largely irrelevant. Whether a drunk driver drives drunkenly, the Court seems to think, is up to him. That is not how I understand the influence of alcohol.'

Thus, says Justice Scalia, “The Court’s opinion serves up a freedom-destroying cocktail consisting of two parts patent falsity.”

I don’t know about anybody else, but I love this stuff. And there’s something great about America when we have some of our greatest legal minds seriously arguing over the legitimacy of a traffic stop.