Category: worship

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

Worship Pastor as Tour Guide

A couple weeks back I linked to a two hour panel video discussing The Worship Leader as Pastoral Musician. I’ve finally gotten all the way through the video and want to highlight some thoughts from it that stuck out to me. The first one I want to talk about is Worship Pastor as Tour Guide.

This thought comes from Sandra Maria Van Opstal, who after 15 years with InterVarsity currently serves as Executive Pastor of The Grace and Peace Community, a church community associated with the Christian Reform Church on the northwest side of Chicago. She says [around the 25:00 mark in the video]:

The fact that worship leaders are pastors means that we meet people where they are, and we’re responsive to them, but we also lead people to new places where they need to go, and create spaces to introduce people to practices that form them…. It’s like a tour guide. If you come to Chicago and you’re really into sports, I’m going to take you to all the stadiums, and show you all that stuff - I’m not into it, but I’ll take you, because I’m a good tour guide. I’m asking what is on your mind, what is important to you. And then, I’m also gonna take you to places in my city that you don’t even know exist, because they are fundamentally what it means to be in Chicago. You can’t eat deep dish every time you go to Chicago. There is so much other food that exists there. So in the same way we as pastors don’t only meet people where they’re at… we also have to take them somewhere.

Sandra goes on to talk about how this relates to addressing current events and issues, and leading a congregation to lament and open discussion rather than just ignoring the issues.

I also see an application for worship pastors as it relates to music selection and service content. Yes, we need to meet people where they are, to speak in their musical dialect, in the words of Sandra’s metaphor, to show them the places they want to see. But we can’t stop there. We then have to take them to where they need to go in worship and formation.

In my church’s mission statement we talk about coming alongside people as they take their next step toward Jesus. This pastoral “tour guide” activity is placing an arm around their shoulders and helping them head in the right direction as they take that step. What a great picture.

The worship leader as pastoral musician

Zac Hicks shared this video last week - it’s a two-hour long panel discussion at Calvin College on the topic of “The Worship Leader as Pastoral Musician”. The panel includes worship pastors from a wide variety of backgrounds and an academic who has made a study of evangelical church music.

I’m only 30 minutes into it so far but I’ve already noted several timestamps that I want to go back and transcribe and write more about… this is a really good discussion. Worth two hours if you’ve got them.

The Worship Industry is "Killing Worship"?

Self-described post-evangelical (and Methodist worship pastor) Jonathan Aigner wrote on Patheos recently on “8 Reasons the Worship Industry Is Killing Worship”. I both resonated and disagreed with enough of his post that I figure it’s worth a short response.

Aigner’s eight points, with my thoughts interspersed:

1. It’s [sic] sole purpose is to make us feel something.

Aigner says that the worship industry “must engage us on a purely sensory level to find widespread appeal…”

I’ll agree with Aigner here on the overall concept and disagree with him on the breadth of his statements. Does the worship industry rely too heavily on the sensory level to get us engaged? Probably, yeah. But is it affecting us “purely on an emotional level”, as he claims? I won’t go that far.

2. The industry hijacks worship.

“When the mind is disengaged and worship is reduced to an emotional experience,”, says Aigner, “worship descends into narcissistic and self-referential meaninglessness.” This point relies on your accepting his point #1, so given that I’ve only partially granted it, I’m on the fence here, too. When worship music completely disengages the brain and works solely on emotion, I’d agree that it becomes fairly meaningless. But I don’t think that’s happening quite as broadly as he asserts.

3. It says that music IS worship.

Now we’re finding common ground. In our current evangelical mindset, “worship” is too often just the music part of the service, to be joined up with “announcements”, “preaching”, etc. Our thoughtful members would probably nuance the definition if asked, but it’s very easy for anyone, including myself, when leading worship music in the service (see how I just slipped into it there?), to lazily allow just the music to be referred to as “worship”.

4. It’s a derivative of mainstream commercial music.

Yes… but.

As my wife can attest, I have gone off on many a rant about how Christian music so obviously follows mainstream music, just 5 years behind.

Say, for example, when I saw Chris Tomlin’s video of his song “God’s Great Dance Floor” (a concept that I don’t even really want to explore from a theological standpoint, but that’s beside the point), where he matches Coldplay’s Chris Martin in musical style, jacket, and even awkward white-guy dancing.

Or when I realized circa 2012 that DC*Talk’s “Jesus Freak” copied Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” down to the same chord sequence for the intro. (Points to the late Kurt Cobain for at least not adding a rap about a belly jiggling and ‘a typical tattoo green’.)

But on the other hand… all music is derivative. Commercial music just like church music. For every truly groundbreaking artist you will find a dozen knock-offs popping up a few years later. History has a way of preserving the good ones and weeding out the bad ones. So while some music is so derivative of better mainstream versions that you just have to avoid it, being derivative, by itself, isn’t killing us.

5. It perpetuates an awkward contemporary Christian media subculture.

“[Christian worship music] can’t possibly find itself in Bernstein’s five percent because it’s too busy talking about how “Christian” it is, instead of telling the story.

That’ll preach.

6. It spreads bad theology.

I’m sympathetic here, too, but this is not a factor unique to modern church music. Again, history has a way of weeding out the really atrocious stuff, but you will find theological nightmares in classic hymnody, and you will find beautiful pieces of good theology in modern songs.

7. It creates worship superstars

Aigner clarifies that he’s really complaining about the rock star persona many worship artists take on and the fandom that grows from it. And he’s got a decent point. “We the church become an audience. Groupies. Screaming teenagers for Jesus.” Yep.

That being said, when I hear “worship superstars”, my first thoughts run along the lines of Charles Wesley, Fanny Crosby, Isaac Watts, J.S. Bach… We all have our superstars. The modern ones just have to deal with the modern trappings of celebrity that go along with fandom in this culture.

8. It’s made music into a substitute Eucharist.

Here’s where I think Aigner has a point that’s well worth considering - not necessarily as much for how it critiques our value of the music as it does our value of the Eucharist. I’ll quote him at length:

Most evangelicals, along with the mainline Protestants who are looking to commercial Christian music as an institutional life preserver, use music as if it were a sacrament. Through their music, they allow themselves to be carried away on an emotional level into a perceived sensory connection with the divine. Music is their bread and wine. Don’t believe me? Try telling your church, your pastor even, that we should make a switch. Let’s have Communion ever week, and music once a month (or where I come from, once a quarter). It probably won’t go over well.

That point hits home in my third-Sunday-of-odd-numbered-months-practicing church.

Overall, I appreciate Aigner and people in his camp pushing us toward theological excellence, away from the celebrity worship culture, and toward the Eucharist. On the whole, though, his discussion points might still need some work.

That old, old impulse to tweak and re-write

As a worship leader I confess I grumble from time to time about the current propensity of our songwriters to appropriate and revise classic hymns in ways that just drive me crazy.

For example, my worship pastor has heard me rant on more than one occasion about Chris Tomlin’s modification of the last verse of Crown Him With Many Crowns. The original lines directly address Jesus:

All hail, Redeemer, hail, for Thou hast died for me, Thy praise and glory shall not fail throughout eternity…

But Tomlin, for some reason that doesn’t entail the rhyming scheme, revises the words to talk about Jesus rather than to Him:

All hail, Redeemer, hail, for He has died for me, His praise and glory shall not fail throughout eternity…

Why, Chris, why? You could’ve modernized the language without screwing around with the perspective of the song. Argh.

Oh, and don’t even get me started about the multiple Christian-ese re-writes of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah”. Yikes.

OK, I’ll get off my soapbox.

This past weekend we had a garage sale, and among 3 big boxes of sheet music my Mom brought to the sale, I found a book that lets me know that this isn’t a new problem.

“World Famous Christmas Songs, containing the best and most popular Songs of the Nativity”. Compiled and Edited by the Reverend George Rittenhouse. Published in 1929, it’s an eclectic assortment of both secular and sacred songs.

What stuck out to me as I paged through was that when it says “edited” by Rev. Rittenhouse, they weren’t kidding. His fingerprints are all over this thing.

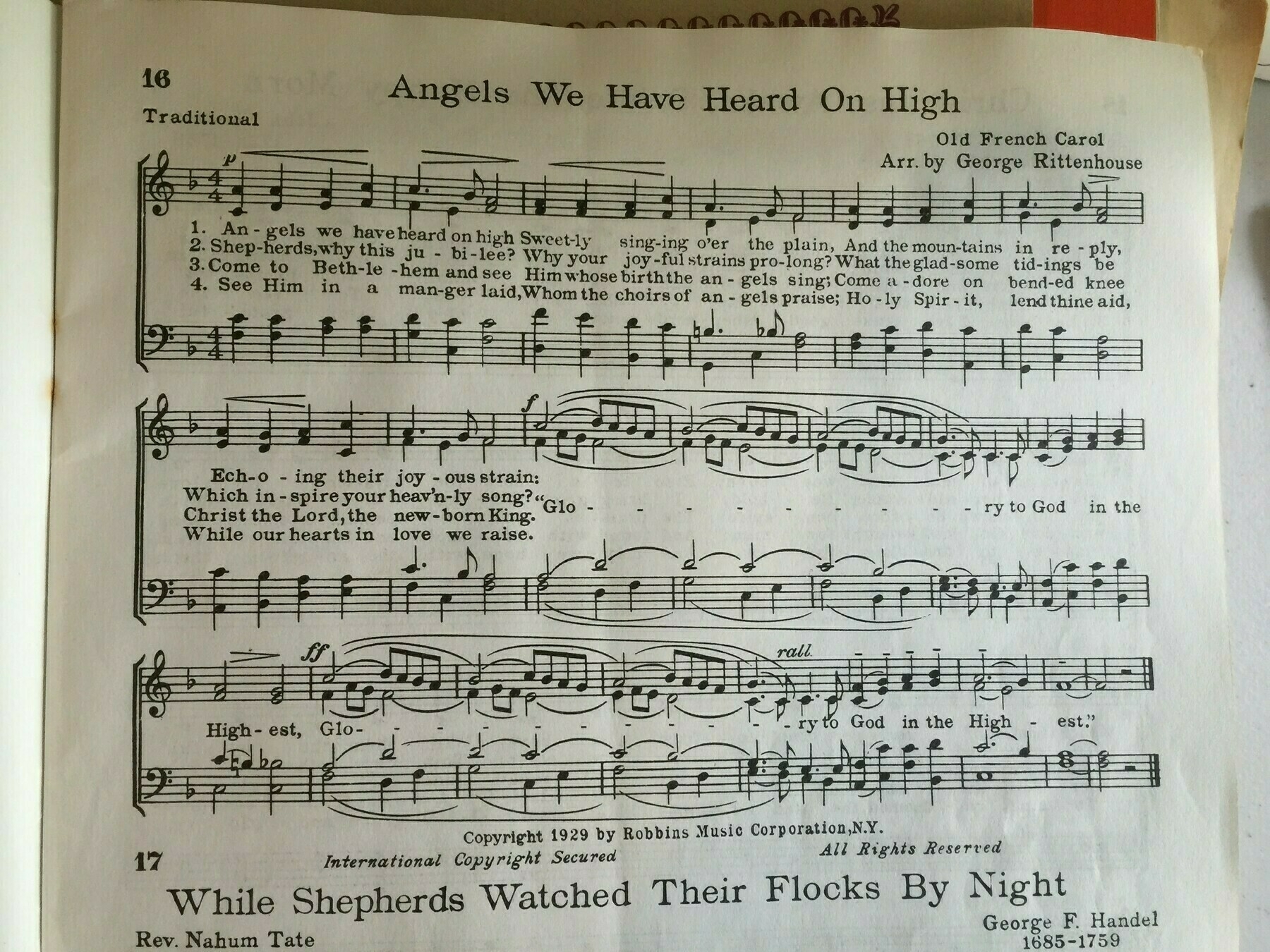

For instance, he rather ambitiously chooses to re-harmonize Angels We Have Heard on High with some extra movement:

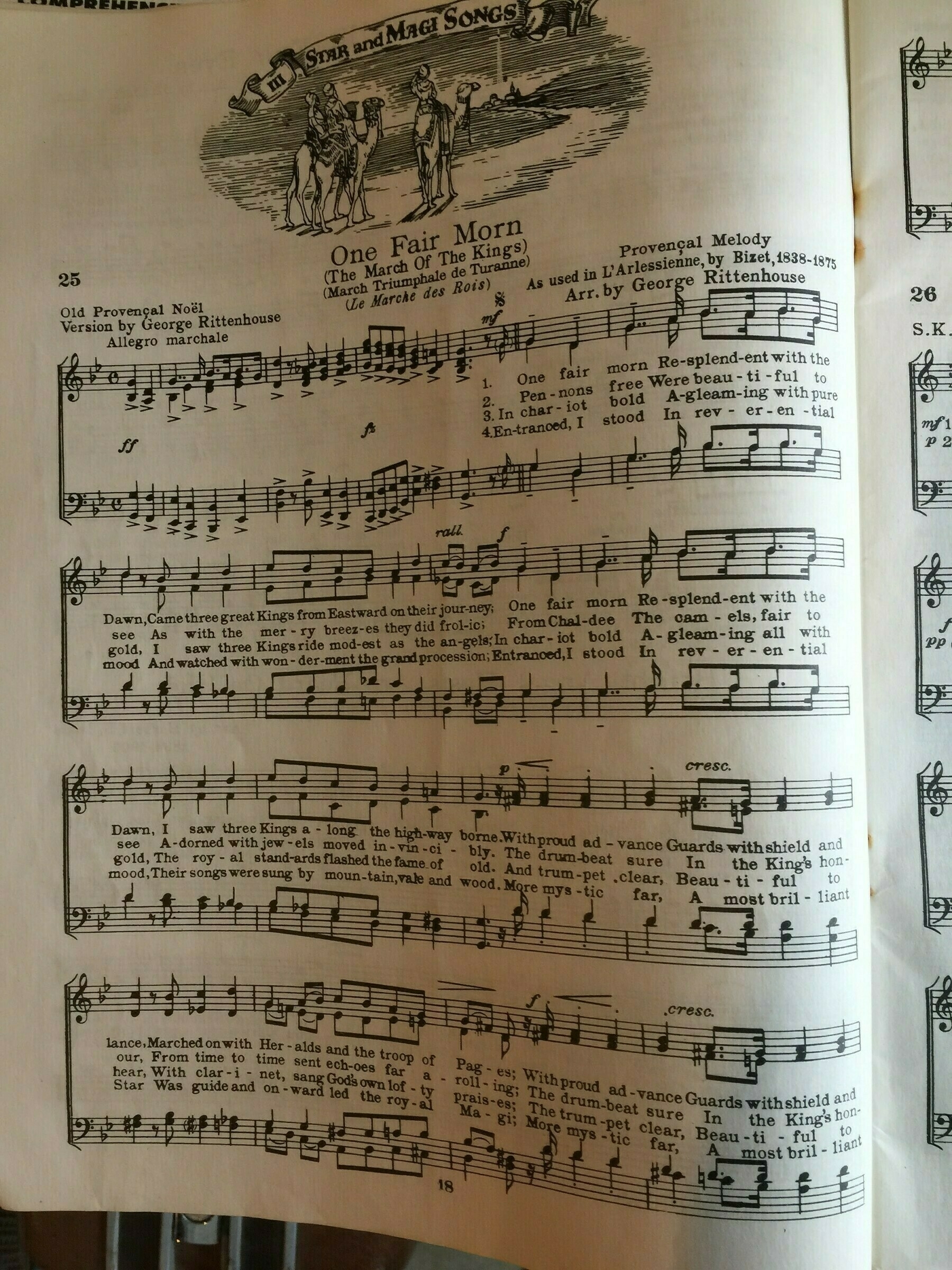

Another place he appropriates Bizet’s L’Arlessienne and some old lyrics to create a rather bombastic tune subtitled “The March of the Kings”.

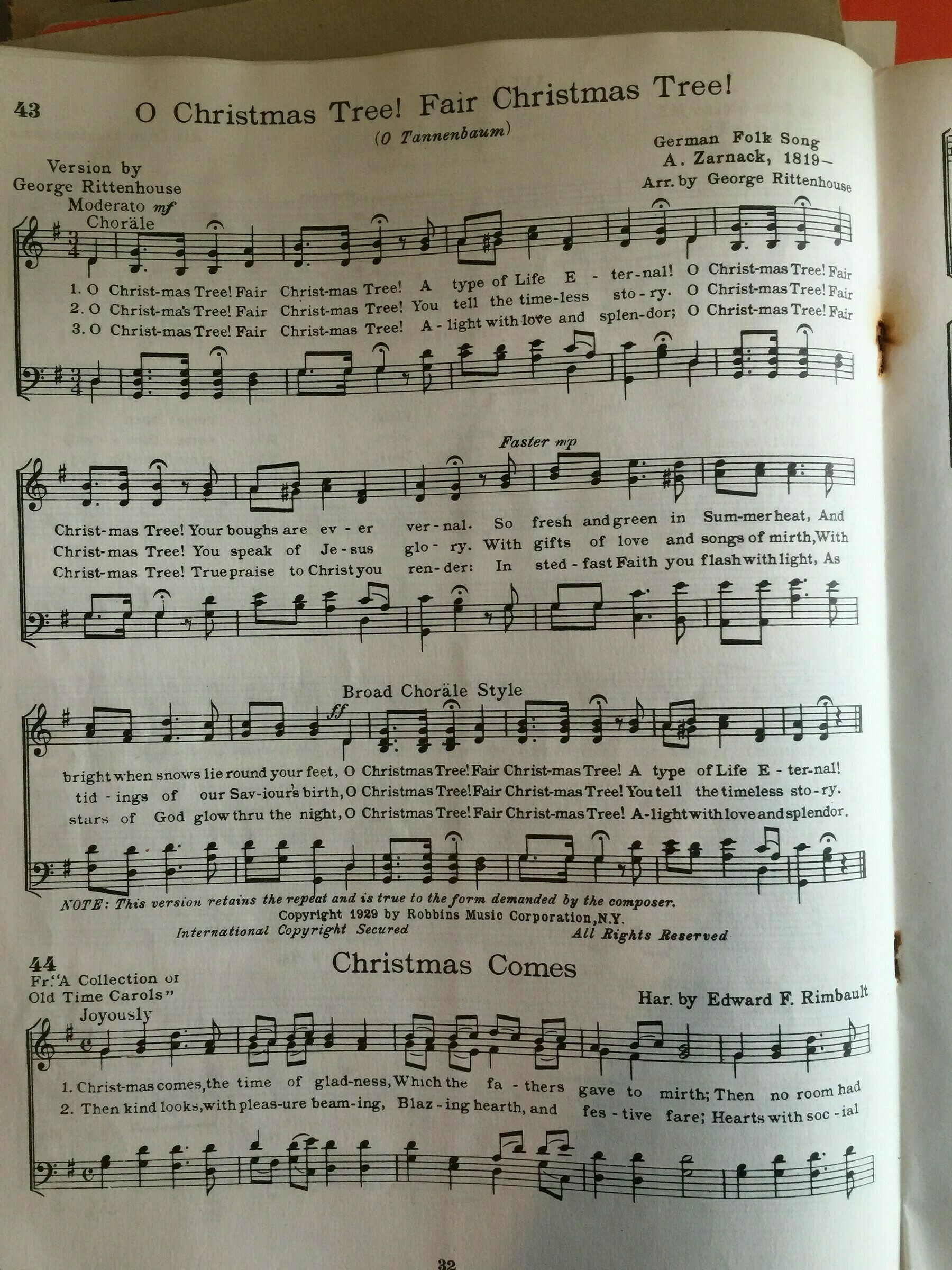

Then there’s this gem, wherein he re-writes the lyrics of “O Tannenbaum!” to give them a Christian angle:

O Christmas Tree! Fair Christmas Tree! A type of Life Eternal! O Christmas Tree! Fair Christmas Tree! Your boughs are ever vernal. So fresh and green in Summer heat, and bright when snows lie round your feet O Christmas Tree! Fair Christmas Tree! A type of Life Eternal!

A classic waiting to happen, right there. There are two more verses if you’re really interested.

The more things change…

I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that these impulses have been around a long time. (Picture a musician in the court of King Hezekiah - “gah, why can’t we just sing that psalm the way King David wrote it?”) But it was comforting to see that confirmation, and to be reminded that history has a way of weeding out the material of lesser quality and holding on to the good stuff.

I guess I can be patient.

Revisiting the evangelical worship experience

A self-professed “child of the 1990s’ Christian subculture” recounts her experience revisiting that culture after many years away from it:

When I pulled into the parking lot for the concert, I immediately had a sense of foreboding. I had mostly come to see a favorite singer-songwriter, well-known in Nashville but still touring with larger acts in other parts of the country. For this concert, she was touring with an old high school favorite, and I didn’t think much of it, except that it might be fun to hear them play again. I hadn’t looked into it any further than that, and had been to plenty of church-based concerts in the years since leaving the evangelical church (for lack of better term), so I had no reason to think this one would be any different. Except that it was.

Susan does an excellent job of not questioning the motives or intentions of the concert audience while still asking some pointed questions about the motivations of the performers and producers, and about how the “worship experience” is managed and (potentially) manipulated.

It’s worth reading the entire thoughtful post.

Worship develops feelings for God, not vice versa

This wonderful little bit of insight came across my Twitter feed this morning and I’ve been chewing on it all day. It strikes me that this is one key reason why the lyrical content of worship songs sung in church is so important to me.

The insipid worship music designed to inspire a feeling nearly always rubs me the wrong way. I’m painfully aware of when my emotions are being manipulated, and I recoil.

On the other hand, when I sing good content, powerful truths, they move me. They sink in and then engage my emotions in worship. But it’s the willingness to come to worship and the truth sinking in to my heart that brings the emotion, and not the reverse.

Thanks, Pastor Eugene.

Practical Worship Leading Ideas

Yesterday I wrote a response to a post wherein someone else argued that church praise bands, by virtue of the type of music they play, speak a special language and have become a worship intermediary for the congregation. I disagreed to an extent, but promised some thoughts on principles for leading worship that can make participatory congregational worship more effective. Here are those thoughts:

Planning

On the planning side we need to carefully consider what new songs we bring into our congregational repertoire. We need new songs. We may find songs that play on Christian radio that are good choices; we will also find plenty there that are not. We will undoubtedly get requests from church members (and leaders!) to sing their new favorite radio song on some Sunday. This may times turn up good new songs; however, it may also be an area where we need to graciously exercise leadership and say no. If a song seems a little bit too simple and too easy for your highly-talented praise band, it’s probably just about right for your congregation.

We also need to be careful about the rate at which we introduce new songs. Back when I was leading on a weekly basis, when it was time to introduce a new song we would sing the song two weeks in a row, skip a week, and sing it again the fourth week before then adding it to our regular repertoire list. I would alsobe sure that every other song we sang those four weeks was a familiar song.

These two suggestions actually complement each other pretty well: if you’re more choosy about what songs you want to add to your repertoire, you won’t feel such pressure to add new songs at an uncomfortable frequency. And you can still manage to work in at least 10 new songs a year, which isn’t bad.

Execution

Lots has already been written on this topic, so I’m unlikely to say anything very new or novel. I love my church’s approach of having a large number of vocalists on the stage; it takes the pressure and focus off of any one or two people being soloists and lets us sing as a mini-congregation right there in the band.

Modern popular praise bands have developed an environment that resembles a rock concert more than a congregational time of worship, and the temptation is there to roll that right into our Sunday mornings. (I’ll leave only one example here.) The issue isn’t that they like to play rock music and that there’s a crowd that enjoys it. The issue is that we often, consciously or not, take it as a model for how our Sunday morning worship should look and sound. And that can be a problem.

If, during congregational worship, the focus frequently gets shifted to a gifted soloist, or a kickin’ guitar solo, or some novel and funky instrumentation, it’s a distraction. We’ve verged into concert territory and turned our congregation into an audience for the band instead of regular participants in worship. (There’s still room for ‘special music’, though. I’ll get to that.)

Really Leading

The other key thing we can do as leaders during the service requires a focus on that word: leading. One of the nicest things a person ever said to me after I led music in a service was that they felt like I had really led them; that there was no uncertainty about what was coming next, or what they were supposed to be doing; they were able to just comfortably settle into worship.

Here’s where we can be very practical in our leadership. If we’re introducing a new song, we should say so up front. If a band member is going to sing the first verse solo to allow everyone else to learn the tune, cue the congregation to that fact so they don’t feel the uncertainty of wondering when they’re expected to sing.

There’s still room for “special music” if that’s a regular part of your worship tradition, but set it apart in the service in a way that it’s clear what the intent is. By saying “Julie has a song to share with us now, so please have a seat and listen to the message of this song”, we can prepare our congregation to receive the song far better than if we just have the soloist start singing as if the song were just another part of the worship set.

Physical and verbal cues during songs are important ways to lead, too. Especially in songs where there may be more time between verses - provide clear cues to the congregation as to when to come in. Maybe just call out the first few words of the next line. (The person running your lyrics on the projector will appreciate this, too!)

Wrapping Up

Leading worship is an art as much as a science, but if we can approach it humbly and pastorally we will always be finding ways where we can improve as leaders, with the result being more appealing and engaging worship services. It should never be about us; it should always be about Him.

Do Praise Bands speak a Secret Language?

Yesterday I ran across a recent post from Lutheran pastor Erik Parker provocatively titled “Praise Bands are the new Medieval Priests”. In it Rev. Parker says that praise bands are alienating him from worship.

I just can’t access Praise music anymore, I don’t hear Praise songs as the music of worship. I find myself wondering why I am just standing there, in the midst of a group of people who are also not singing. As the Praise band performs song after song, I am consistently lost as to how the music goes, what verses will come next, how to follow the melody, when to start and stop singing, or when a random guitar solo will be thrown in right when I thought I had figured out when the next verse starts.

Parker recounts a recent church service where he observed that even as the very talented praise band was playing beautiful music, the people in the pews were, for the most part, “not really being a part of the music at all”, but rather just bystanders, “being played at, rather than played with”.

Parker draws the analogy that modern praise bands are the new medieval priests - leading worship in a ’language’ that few speak or can participate in. As such, he claims, “Praise Bands are incompatible with a worship that is done by the community… they are a performative medium, not a participatory one.”

I posted a link to the piece on Facebook last night and got an interesting mix of responses. A friend who has recently been looking for a new church noted that being directed to raise her hands to a song she has never even heard before makes her feel like a bystander rather than a participant in worship.

Another friend who grew up on the mission field in Africa said that music in small African churches that can’t afford a sound system is much more participative than in those that can. As he notes: “human nature being what it is, everyone turns it [the volume] up.”

What Language is that, again?

Full disclosure: I’m a member of a praise band. I have spent nearly all of my adult life either leading or playing in praise bands on a regular basis. So I clearly am unlikely to agree with the full premise of Rev. Parker’s post. However, I think he has identified some concerning symptoms, even if he has perhaps misidentified the true problem.

I share Rev. Parker’s concerns about planning congregational music that is regularly unfamiliar and difficult to sing. I have been a part of rehearsals where a team of professional-caliber musicians have had to work for a solid hour to get one new song learned to the point where we can sing and play it consistently. I have on more than one occasion wondered out loud how the congregation had any chance of singing the song on their one time through it if it took the band an hour to figure it out.

Don’t get me wrong - it’s imperative that we continue to teach our congregations new songs. But when our primary musical influence is Top 40 Christian radio, the songs we’re pushed to select are often difficult songs to sing, often requiring an unnaturally large vocal range and designed for professional vocalists. That concerns me.

A similar issue often exists with song familiarity. If my own experience is representative at all, our ‘best’ worship times come when we sing familiar songs. Familiarity allows us to think less about learning the words, melody, and arrangement, and think more about the message of the song. It’s no accident that a congregation stands mostly silent as the band leads a new song from the radio but then wholeheartedly belts out all four verses of a 200-year-old hymn.

It’s not (necessarily) about the band.

Where I think Rev. Parker gets it wrong is in pointing the finger at the Praise Band as the issue. The praise band is not the issue. Praise bands, playing in pretty much any style, can do music in a way that engages and draws in a congregation, or can do music in a way that pushes the congregation off to be ’the audience’ rather than ’the body’.

Rev. Parker makes a fair point that style can distract from real congregational worship. As he puts it, “rock bands are by design meant to overwhelm the audience with sound.” And I agree with him that overwhelming a congregation with sound isn’t conducive to congregational worship. But I’ve also attended services in Parker’s own denomination where more traditional instrumentation was used in a way and at a volume that still served to overwhelm the congregation. So it isn’t strictly about instrumentation or style.

However, there are planning and execution aspects that as worship leaders we can focus on to provide consistent inclusive congregational worship. Rather, though, than turning this into a two-thousand-word post, I think I’ll save those ideas for tomorrow.

Losing something in the modernization

This past Sunday our worship team learned and led a new (old) song - Chris Tomlin’s arrangement of (and new chorus for) the old hymn Crown Him With Many Crowns.

On the whole, I like it. If adding a contemporary chorus is what it takes to get us singing two and a half verses of densely-packed truth in a classic hymn, that’s a deal I’m willing to make.

Aside: the density of theological truth in this old hymn, when compared to what’s in most modern songs, is really stunning. But that’s a post for another time.

The one quibble I’ve got with Tomlin’s update to the hymn, if you’ll allow me to be pedantic for a minute or two, is in the updates to remove the archaic articles. Now, I’m not, in principle, against removing them. Thee, Thou, and Thy aren’t in common usage any more, and a careful update can give the classic text a fresh new feel. But the changes here aren’t so careful, or at least they’ve sacrificed accuracy in favor of rhyming schemes. A couple of examples:

From Verse 1, the original:

Awake my soul, and sing Of Him who died for Thee And hail Him as thy matchless King Through all eternity

And the update:

Awake my soul, and sing Of Him who died for me And hail Him as thy matchless King Through all eternity

That second line is a challenge to modernize, because getting lines two and four to rhyme really depends on having that long E sound at the end of line two. And replacing “thee” with “me” doesn’t actually change the theological content in any particularly objectionable way.

But it changes the perspective of the verse. In the original, the author calls his soul to sing, because Jesus died for his soul. In the update, the soul is called to sing because of the salvation of the author. A minor difference, but (at least to me) frustratingly annoying.

The second issue comes in what was the tail end of the fourth verse in the original, but which Tomlin has repurposed as a bridge in his version.

The original:

All hail, Redeemer, hail! For thou hast died for me; Thy praise and glory shall not fail throughout eternity.

And the update:

All hail, Redeemer, hail! For He has died for me His praise and glory shall not fail Throughout eternity.

And it’s the same problem - what the heck do you use to rhyme with eternity? A friend on Facebook pointed out that the problem (quite obviously, upon reflection) isn’t with rhyming ’eternity’. Doh!

This time I dislike the solution quite a bit more, because it changes the direction of the lines. In the original hymn, the hymnwriter turns to address Christ directly at the end. “All hail, Redeemer, hail! You have died for me!” But the reworking turns it into an account of Christ’s work rather than a direct stanza of praise.

Again, it’s still not wrong, but it really loses something in the translation.

OK, yes, I’m being pedantic. I’m still happy we sang the song, and I hope we include it in our regular song rotation. But I’m also still tempted to conclude that maybe the better lesson for the modern church would be to learn to sing and appreciate some of these classic hymns without forcing them to fit our modern musical sensibilities. Or maybe I’m just getting crotchety in my late 30’s.

On Playing and Variety

My primary instrument has always been (and likely always will be) keys of some sort. I started piano lessons when I was 7. I started playing for church at age 14. I first started playing with a church worship band in college at age 19. I’ve led worship while playing the piano hundreds of times. Those fingers on the keys at the top of my blog are my fingers, playing piano at my sister’s wedding.

Back in high school I taught myself to play guitar, and I’m a reasonable hack there, though my fingerings are never very clean. From there I did a lot of playing bass lines on the guitar, though I’ve only played bass as part of a band a handful of times. Keys are where it’s at for me. And that’s worked to fill the need where I’ve been. After college there haven’t been an abundance of other keyboardists.

For the last year or so, though, while I love playing keys in the worship band, the instruments that are in my head all the time, the ones I dream about playing, are bass and drums. I’m not sure why. Maybe because so much of the music I listen to is guitar/bass/drums driven instead of piano-driven? Maybe I’m just getting bored with piano right now?

In reality, I’m a passable bass player. I can keep tempo on the drums, but one listen to a real drummer (of which we have several at church) quickly reminds me that I’m just a hack. (Of course, I have no practice… maybe I’d pick it up quickly?)

I don’t know where this leaves me or even really what my conclusion is. It’s just odd to observe that after having piano ingrained in my brain for almost 30 years, I’m now doing a lot of my primary thinking in terms of other instruments. (It’s suppose it’s also entirely possible that piano is just so ingrained that I don’t notice it any more.)