Category: theology

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

Reimagining Orthodoxy

Dr. Chris Green shared part of an essay today on a theology of disagreement. There’s a ton of good stuff in it. For example, early on:

Truth be told, what seem to be theological disagreements very often arise from and are borne along by other conflicts rooted deeply in hidden personal and interpersonal anxieties and ambitions. But at least some of our theological disagreements, I want to insist, are in fact the upshot of the Spirit’s transforming work taking shape in our as-yet-unperfected lives, moving us toward the “fullness of Christ” in which we find shalom.

This represents a beautiful freedom that I never found in my life in the American evangelical church.

But further, I want to commend to your thinking what he says about orthodoxy. In the evangelical and fundamentalist church, “orthodoxy” tends to be a cudgel used to keep unwanted questions and questioners away, and to scare the flock away from being tempted toward theological ideas that stray from the party line. Green, though, quotes Rowan Williams to suggest a different approach:

[W]e must reimagine the nature and purpose of orthodoxy. Instead of conceiving of it as a wholly-realized, already-perfected system of thought, we need to recognize it as a fullness of meaning toward which we strive, knowing full well we cannot master it even when in the End we know as we are known. Because the Church’s integrity is gift, not achievement, we can never know in advance “what will be drawn out of us by the pressure of Christ’s reality, what the full shape of a future orthodoxy might be.”

He continues, quoting Williams further:

Orthodoxy is not a system first and foremost of things you’ve got to believe, things you’ve got to tick off, but is a fullness, a richness of understanding. Orthodox is less an attempt just to make sure everybody thinks the same, and more like an attempt to keep Christian language as rich, as comprehensive as possible. Not comprehensive in the sense of getting everything in somehow, but comprehensive in the sense of keeping a vision of the whole universe in God’s purpose and action together.

A lot to chew on there, but I love the vision of orthodoxy as a commitment to keeping a vision for God’s continuing purpose and action to which we are only slowly understanding. Beautiful stuff.

You get the feeling from reading them that we might be loved

This old concert recording of Rich Mullins at a Wheaton College chapel service in 1997 is an internet classic, but listening through it again today I was struck by his wisdom about the love of God:

I am at an academic place so I need to speak highly of serious stuff. Although I have trouble with serious stuff, I have to admit, because I just think life’s too short to get too heavy about everything. And I think there are easier ways to lose money than by farming, and I think there are easier ways to become boring than by becoming academic. And I think, you know, the thing everybody really wants to know anyway is not what the Theory of Relativity is. But I think what we all really want to know anyway is whether we are loved or not. And that’s why I like the Scriptures, because you get the feeling from reading them that we might be. And if we were able to really know that, we wouldn’t worry about the rest of the stuff. The rest of it would be more fun, I think. Cause right now we take it so seriously, I think, because of our basic insecurity about whether we are loved are not.

I think you should study because your folks have probably sunk a lot of money into this, and it’d be ungrateful not to. But your life doesn’t depend on it. That was what I loved about being a student in my 40s as opposed to in my 20s is I had the great knowledge that you could live for at least half a century and not know a thing and get along pretty well.

Playing the Jeremiah 17:9 Card

“The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked; Who can know it?” – Jeremiah 17:9, NKJV

I had someone play the Jeremiah 17:9 card on me the other day. We were winding up a long email conversation wherein I finally was able to make clear that the standard evangelical hermeneutical approach to the Scriptures isn’t particularly appealing to me any more - that there are other approaches I find more compelling. (Brian Zahnd’s post Jesus Is What God Has To Say captures it pretty well for me right now at a high level.)

Once I got that message across, the message from my conversation partner was simple: beware your motives and understanding, because, after all, the heart is deceitful above all things!

In the evangelical circles I’ve spent my life in, Jeremiah 17:9 is used as a sort of ultimate trump card. If a discussion starts to go sideways, if someone comes to a logical conclusion that something they’ve been taught just can’t be correct, if someone questions how God could possibly be in the right for, say, ordering the murder of innocent children, this is the fallback. Of course your heart rebels against that thought. Your heart is deceitful above all things and desperately wicked! You need to accept that what we are teaching you is correct and ignore any prompting inside you that says otherwise!

There are problems, thought, with the Jeremiah 17:9 card.

Logical Coherence

First: playing the Jeremiah 17:9 card is logically incoherent. How did the card player become convinced of the rightness of their position in the first place? Undoubtedly through some combination of study, reasoning, and internal desire (even if subconscious) to hold that position. So how does the card player know that it isn’t his own heart that is deceiving him rather than yours deceiving you? If our heart (i.e. our reasoning as supplemented and powered by our instincts) is deceitful, what basis do you have for claiming that yours is so much less deceitful than mine that your conclusion is right and mine is wrong?

Other Bible Verses

I don’t recommend pulling single verses from their context and using them to justify positions. It’s a bad way to understand the Bible. But if you’re going to play that game, there is a broad selection of other verses about the heart that might provide an alternative perspective to Jeremiah 17:9.

Proverbs 4:23: “Above all else, guard your heart, for everything you do flows from it.” - This sounds like your heart has something good in it that needs to be protected!

Psalm 51:10: “Create in me a pure heart, O God, and renew a steadfast spirit within me.” - The psalmist sure seems to think that purity of heart is a goal worth asking for and attaining to.

Proverbs 3:3: “Let love and faithfulness never leave you; bind them around your neck, write them on the tablet of your heart.” - We can have love and faithfulness written on our heart!

Ezekiel 36:26: “I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit in you; I will remove from you your heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh.” - If God gives me a new heart and a new spirit, maybe that new heart is good?

2 Corinthians 9:7: “Each of you should give what you have decided in your heart to give, not reluctantly or under compulsion, for God loves a cheerful giver.” - This one is kinda fun… decide in your heart what to give! God will be happy with this!

Psalm 119:11: “I have hidden your word in my heart that I might not sin against you.” - This one speaks directly to the effects of discipleship upon the heart - the heart is improved and the result is less sinning!

Hebrews 3:12: “See to it, brothers and sisters, that none of you has a sinful, unbelieving heart that turns away from the living God.” - The existence of a “sinful, unbelieving heart” implies the existence of a holy, believing heart that is turned toward God.

Proverbs 23:15: “My son, if your heart is wise, then my heart will be glad indeed.” - Solomon suggests that a heart can be wise!

I hope the point here is clear - if you want to play the game of cherry picking to proof-text your point, why is the Jeremiah 17:9 card a more valid and applicable cherry than any of these verses?

Potential for Gaslighting and Abuse

Gaslighting is a strategy in which a perpetrator bends another person’s sense of reality and belief system, making that person second-guess themselves in a way that is beneficial to the perpetrator. Typical gaslighting phrases include things like this:

-

“Do you really think I’d make that up?”

-

“I did that because I love you.”

-

“You’re too sensitive.”

-

“It’s not that bad. Other people have it much worse.”

-

“I don’t know why you’re making such a big deal out of this.”

It’s not hard to see how “the heart is deceitful above all things” could fit right in to a gaslighting strategy. A spiritual leader abuses a person in some way. That person responds with a concern. This doesn’t feel right. Something is off here. The leader points right to Jeremiah. Your heart is deceitful and desperately wicked. Don’t trust it. And the abuse continues as the victim is further confused between the truth of the matter clear to their conscience and the deception and malpractice of their abuser.

Finally

A robust examination of discernment - how it works, how we integrate our instinctual “gut feelings”, how we experience the influence of the Holy Spirit, how we come to understand God’s Word and leading through the wisdom of community - would require far more words than I could write here. Whatever discernment is, though, it’s certainly not so simply summed up as “your heart is deceitful, don’t trust it”.

Instead of living in a constant spirit of fear, Christians should live in a spirit of confidence that God is guiding them. If you’ve made it this far, you’ll forgive me one proof-text for this that also suggests God wants us to use our minds, too.

For God has not given us a spirit of fear, but of power and of love and of a sound mind.

2 Timothy 1:7, NKJV

_Playing card illustration via the Redemption CCG Fandom wiki._

My own personal Philippians 3

If someone else thinks they have reasons to put confidence in the flesh, I have more: circumcised on the eighth day, of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of Hebrews; in regard to the law, a Pharisee; as for zeal, persecuting the church; as for righteousness based on the law, faultless.

But whatever were gains to me I now consider loss for the sake of Christ. What is more, I consider everything a loss because of the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord, for whose sake I have lost all things.

–The Apostle Paul, Letter to the Philippians

I have many times read this passage and heard it taught with the message “your family history and good works don’t matter, only giving up everything and serving Jesus matters”. As I read it today, though, where I am in my Christian journey, it hits a little bit different.

My own personal Philippians 3

If anyone thinks they have confidence in their evangelical Christian credentials, I have more.

I prayed to ask Jesus into my heart when I was 3. I was baptized by immersion at a Christian & Missionary Alliance church after giving testimony to my faith when I was 7 or 8.

My church started AWANA clubs when I was in first grade. I completed 3 years worth of Sparks club in 2 years to get the associated trophy. I completed every year of AWANA after that, all the way through high school, memorizing hundreds of Bible verses. I was given the AWANA Citation Award at AWANA national Bible Quizzing and Olympics. My team didn’t win the Olympics, but won the sportsmanship award, which is probably even more meritorious.

I was homeschooled in a Christian homeschool grades 1 through 12. I learned from the best Christian curricula. I soaked up Ken Ham’s creation science videos in Sunday School and youth group. As a 7th grader I sent a letter to my best friend, aghast that he entertained the possibility of “long-day” creation. I quoted 2 Timothy 4 to him and said I would be one of the ones who stood up when others were going wobbly.

I attended an IBLP Basic Seminar when I was in high school. I bought and took home a cassette tape of their Gothard-blessed choir arrangements of hymns, excited to have Godly music to listen to. I attended a church with the authors of a Quiverfull book and the midwife who reported in Gothard’s newsletter that a Cabbage Patch Kids doll was being used by the devil to prevent a healthy home birth.

I was fully invested in the political implications of my evangelical faith. I speed-dialed Rush Limbaugh and tried to convince his call screener that I should talk to Rush about the dangers of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. I bought a constitutional law overview book written by Michael Farris and was jittery with excitement when I got to hear him speak and shake his hand. I marched in a parade carrying a campaign sign for a Republican Senate candidate.

I sat in years of adult “precept by precept, line by line” Bible study. I went through Evangelism Explosion training, memorized all the cards, and went door-to-door asking people “if you died tonight, and God asked ‘why should I let you into my heaven?’, what would you say?”.

I passed up full-ride scholarship offers to public universities and instead took out loans to attend a Christian university. I lived in a dormitory that only allowed opposite-gender visits for 3 hours on Friday nights and 3 hours on Sunday afternoons under supervision. I took 15 credits of Bible and Christian ethics along with my engineering classes in order to graduate.

I started leading worship in church when I was in high school. I led worship at church and in college chapel during my college years. I joined a Baptist church within the first month of moving to Iowa and within the first year was leading worship there. I formed the team, led practices, led the music at multiple services every week for years. I met weekly with the church staff to evaluate the previous week’s services and plan for the upcoming week.

I became a deacon at that Baptist church before the age of 30. Then I became an elder. I attended the Emmaus Bible College pastor’s conference, the Moody Bible Institute pastor’s conference, and the Desiring God pastor’s conference. I led Bible studies, did in-home pastoral care visits, tracked giving and sent out yearly giving receipts.

I was part of an elder team that planted a new church in an under-churched neighborhood near downtown in our city. I did tech setup and tear-down and led worship there every week for two years.

I moved to a larger Evangelical Free church. I served on the worship team there and became the interim music ministry leader when the staff worship pastor left. For multiple years we did three-service weekends spanning Saturday night and Sunday morning with full band and tech team.

I read hundreds of books on theology and the church. I read John Piper, Tim Keller, Don Carson, Francis Schaeffer, Mark Driscoll, Russell Moore, and N. T. Wright. I led book discussions, wrote blog posts about them, and bought extra copies to give away to others.

I had three children and raised them in the church. I pushed for us to homeschool them. I dragged them to church every time we went. I did read-alouds of the Jesus Storybook Bible and all the Chronicles of Narnia with them. I drove them to youth group, encouraged them to volunteer, taught them instruments or got them lessons so they could join the worship team themselves.

But Jesus

Somewhere in all those years, Jesus stepped in.

Jesus opened my eyes to his love for every person. Even and especially for those who didn’t look like me or believe the way I did.

Jesus made it clear to me that all my book learning and ability to argue people into a corner was a harsh cacophony if I didn’t actually love those people and want their best.

Jesus showed me that God loves my loved ones even more than I do, and that God’s love is the same in kind, and infinitely greater in quality and quantity, as my own love for family is.

Jesus made it clear to me that so much of the memorization and learning and doctrine we were so proud of as evangelicals manifested as unloving, judgmental, manipulative gate-keeping to those who weren’t in our little club.

Jesus helped me see that God’s plan for the universe is so much greater and more redemptive than rescuing a small fraction of holy humans out of a burning earth into an ethereal heavenly plane.

Jesus made it clear to me that his desire is for followers who love God and love their neighbor rather than those who cling to power through politics, nationalism, racism, and misogyny.

Jesus showed me that loving my neighbor might actually mean directly caring for my literal next-door neighbors more than it means laboring to support church programs while I hold good intentions in my heart for others and invite them to those programs.

Whatever my accomplishments were to me, I now count them as nothing compared to knowing the freedom and confidence that Jesus has given me as I now know him as the true representation of God, a God who fully knows, loves, and embraces each one of us just as we are.

Amen.

Stanley Hauerwas on sin, character formation, and fear

From Chapter 3 of Stanley Hauerwas’ book on Christian ethics The Peaceable Kingdom, this wonderful insight into how we can think about sin as interacting with our own power, control, and self-direction (emphasis mine):

We are rooted in sin just to the extent we think we have the inherent power to claim our life - our character - as our particular achievement. In other words, our sin - our fundamental sin - is the assumption that we are the creators of the history through which we acquire and possess our character. Sin is the form our character takes as a result of our fear that we will be “nobody” if we lose control of our lives.

Moreover our need to be in control is the basis for the violence of our lives. For since our “control” and “power” cannot help but be built on an insufficient basis, we must use force to maintain the illusion that we are in control. We are deeply afraid of losing what unity of self we have achieved. Any idea or person threatening that unity must be either manipulated or eliminated…

This helps us understand why we are so resistant to the training offered by the gospel, for we simply cannot believe that the self might be formed without fear of the other.

This gets to the heart of a lot of the discussions I’ve had with my Dad lately about the first step in making a positive spiritual change (which might be what Hauerwas here calls “the training offered by the gospel”) is to be freed from fear. One needs to be secure in their standing with God and with their community to be able to change and grow. (The counter-example here is frequently seen: spiritual communities that make any interest in ideas outside the accepted orthodoxy grounds for exclusion and expulsion.)

Hauerwas continues:

Our sin lies precisely in our unbelief - our distrust that we are creatures of a gracious creator known only to the extent we accept the invitation to become part of his kingdom. It is only be learning to make that story - that story of God - our own that we gain the freedom necessary to make our life our own. Only then can I learn to accept what has happened to me (which includes what I have done) without resentment. It is then that I am able to accept my body, my psychological conditioning, my implicit distrust of others and myself, as mine, as part of my story. And the acceptance of myself as a sinner is made possible only because it is an acceptance of God’s acceptance. This I am able to see myself as a sinner and yet to go on.

This does not mean that tragedy is eliminated from our lives; rather we have the means to recognize and accept the tragic without turning to violence. For finally our freedom is learning how to exist in the world, a violent world, in peace with ourselves and others. The violence of the world is but the mirror of the violence of our lives. We say we desire peace, but we have not the souls for it. We fear the boredom a commitment to peace would entail. As a result the more we seek to bring “under our control”, the more violent we have to become to protect what we have. And the more violent we allow ourselves to become, the more vulnerable we are to challenges.

This is growth toward wholeness: “the means to recognize and accept the tragic without turning to violence”.

For what does “peace with ourselves” involve? It surely does not mean that we will live untroubled - though it may be true that no one can really harm a just person. Nor does it mean that we are free of self-conflict, for we remain troubled sinners - indeed, that may well be the best description of the redeemed. To be “at peace with ourselves” means we have the confidence, gained through participation in the adventure we call God’s kingdom, to trust ourselves and others. Such confidence becomes the source of our character and our freedom as we are loosed from a debilitating preoccupation with ourselves. Moreover by learning to be at peace with ourselves, we find we can live at peace with one another. And this freedom, after all, is the only freedom worth having.

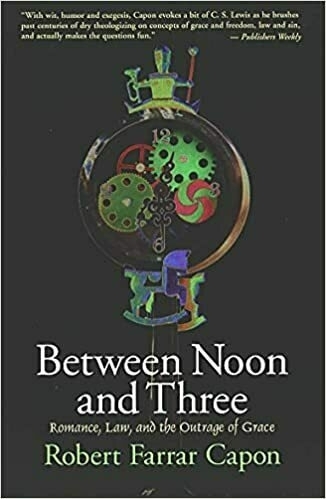

Capon’s Wager on God’s Love

I have on occasion paraphrased something Fr. Robert Capon wrote about God’s love as ”if God is a bastard, we’re all in trouble”. I went digging for the original quote today and came up short of any such choice phrase, but for reference, here’s the longer quote from Between Noon and Three which makes that point, if just a bit less colorfully:

…I have, in this parable, been working only one side of the street — in my effort to do justice to grace, I have neglected justice itself. I am fully aware that in doing so, I have laid myself open to the charge of granting not only screwing licenses but also franchises for far worse things: for pride and prejudice, for torture and exploitation — in short, for getting away with murder.

In my defense, let me point out that Scripture lays itself open to the same charge — and that the other side of the street has been worked so long, so hard, and so often that most people don’t even know there is a sunny side…

But there’s more to it than that. I have expounded Saint Paul to you as saying that not only are we dead to sin but that God is dead to it too — that he has put himself out of commission on the whole subject of blame. And so, indeed, he has: ”I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more.”

I am fully aware that the Scriptures are paradoxical — that God speaks with a forked tongue — and that every lovely thing he says on the side of leniency can be matched by a dozen stringencies that will curl your hair. But I am also convinced that each of us has to make a decision about such utterances. When someone tells you many different things about his attitude toward you, you must first look at him long and long, and decide for yourself whether you care about him at all. But if you finally come to the conclusion that you do care, you must then decide which of his words you will take as his governing word. You ask me why I think God’s leniency governs his severity? Why grace is his sovereign attribute? Well, all I can say to you is that having been a father who has spoken out of both sides of his mouth to six children for twenty-six years — and having all those years believed in a heavenly Father who saves us not by sitting in his penthouse issuing edicts but by sending us the warm, furry body of a Son who drank the nights away with us and died obscurely of the foolishness of it all — all I can say is that I put my bet on the left fork of the tongue. It is my best hope that when my children think of everything I have said and done to them, they choose to remember the times of my severity when I just gave them a kiss on the cheek, poured myself a Scotch, and shut up. And it is my last hope that God hopes the same for himself.

So I really do make no apology for landing on the sunny side of the street. I am sorry if I have offended you; but to me there are some things that simply override everything that comes before or after. And I am sorrier still if you do not feel the same way. For without that ultimate cassation — without that final quashing of the subpoena, that throwing of the prosecution’s case out of court which is the only music there is for the ears of the hopelessly guilty — you and I, Virginia, are simply sunk.

— Fr. Robert F. Capon, Between Noon and Three, Chapter 17

On LGBTQIA+ Affirmation

June 2022 was quite a month for me. It started with the death of a long-time friend. It ended with my being on a phone call with my father while he experienced a stroke-like event. (Turns out: not a stroke. He’s home, and doing ok. Hallelujah.) In the middle was a thing called Pride Month, which had a little more visibility at our home than usual. Two of my kids identify as LGBTQIA+ and have embraced visibility more this year than ever before. (I got their permission to say this here.) So, one of these things is not like the other, but stick with me here and I’ll connect the dots.

Part 1: Online Community

Since Geof died last month, the online community he fostered for nearly 20 years (referred to as “RMFO” for reasons long since forgotten) has been renewed. I have hosted two Zoom “happy hour” calls, and both times 15-20 people have joined, chatted for 2-3 hours, and left with a request that we schedule another one. We have spent these hours catching up on life and recounting our own personal histories as they interact with the RMFO community: singles who met their future spouses in the group; couples once struggling to conceive who now have teenagers; marriages, divorces, job changes, moves, faith evolutions. Online friendships have led to “real-life” friendships, meet-ups, and job opportunities. At the end of the first call I realized that, while I had long considered many of these people meaningful to me, the call helped me realize that I was meaningful to them, too. My thought last week as I closed out the second call: this is the closest thing I’ve had to a healthy, functioning community in my adult life.

During last week’s call I talked about how my own personal views on some issues have evolved over the years, and how I have struggled to find an in-person community (specifically, a church community) where that evolution was welcome. Share those views too loudly and you will be welcome to find some other church to serve and worship at. Five years of quiet discomfort weren’t enough to dislodge me from my last church; their tepid COVID response was the straw that gave me the courage to break the proverbial camel’s back. Two years later I still haven’t found a new place to join. If I’m honest, I haven’t really looked too hard.

Part 2: My Dad

My dad is talking a little slower thanks to the medications he’s on after his health scare, but he’s not talking any less. When we talked last week after he got home from the hospital, we spent a while comparing current reading lists and discussing how some of the books I have given him over the years have helped guide his journey out of a fundamentalist faith into something much more open and gracious. That’s his story to tell, not mine. But what he said toward the end of the call stuck with me: that coming close to death now makes him unwilling to stay quiet on the topics important to him. And I thought to myself: that’s a lesson I should take to heart here in my 40s.

Part 3: Chuck Pearson

Chuck Pearson is a friend of one of the RMFO guys — someone I have never met but have followed on Twitter for years. Last week he posted a beautiful essay about his journey leaving a tenured professorship at a Southern Baptist university when he knew he would eventually be required to sign a “personal lifestyle statement” that would “[force] him to disown his LGBTQ+ friends and family”. Chuck ultimately found a post at another university, but still sat quiet about the topic of LGBTQ+ inclusion:

Ultimately, it stayed private because I didn’t want to burn those bridges. Even as I made that realization that I had to choose between two sides I cared about deeply, I couldn’t bring myself to take that final step of declaring my choice.

In his essay, Chuck quotes from an Alan Jacobs essay from 2014 that argues for Christians to stand firm against the cultural evolution of views on sexuality. Here is Jacobs’ conclusion [preserving the emphasis from the original post]:

Either throughout your history or at some significant point in your history you let your views on a massively important issue be shaped largely by what was acceptable in the cultural circles within which you hoped to be welcome. How do you plan to keep that from happening again?

Clearly Jacobs has in mind a call to resist the desire to be welcomed by “the world” by accepting “worldly” views on sexuality. But for me his question takes the exact opposite orientation. How long have I been convinced about full acceptance of LGBTQIA+ people in the church but been afraid to say so, knowing that it would make me unwelcome in the evangelical church circles I have run in my entire life? Far too long.

Conclusion

So let me make a long-overdue statement as clearly as I can. I am a Christian, and I affirm those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual as they are, unconditionally, including their full inclusion into the assembled body of Christ known as the local church. I know there are those who would say I cannot hold that view and be a Christian. I reject that assertion.

There are multiple serious approaches to the Scripture on the topic which I will not go into here. Suffice it for now to say that you cannot read Scripture as a flat text. It is the product of thousands of years of God’s progressive revelation as understood and recorded by humans. In the end you have to come to some conclusion on which texts capture most clearly the essence of who God is, and use those as the framework from which to understand the rest.

And so, to quote Brian Zahnd:

God is like Jesus.

God has always been like Jesus.

There has never been a time when God was not like Jesus.

We have not always known what God is like—

But now we do.

Jesus taught these two principles in summation of all the teaching: love God with everything you have, and love your neighbor as yourself. He embraced the outsiders and rebuked the self-righteous. He called us to follow Him in lives of self-sacrificial love.

In addition to Jesus’ teaching, we have the witness of the Holy Spirit in the lives of our LGBTQIA+ brothers and sisters — so many dear, tender souls who consistently model what it means to follow Jesus, even in the midst of a church that rarely welcomes them. And to that I can only respond as the Apostle Peter did after first seeing the conversion of Gentiles to Christ: “Can anyone object to their being baptized, now that they have received the Holy Spirit just as we did?” (Acts 10:47)

Rachel Held Evans summarized it this way: “The apostles remembered what many modern Christians tend to forget—that what makes the gospel offensive isn’t who it keeps out but who it lets in.”

To this I say: Amen. May it be so.

Keeping theology coupled with cosmology

I was introduced to Dr. Ilia Delio a couple weeks ago on a podcast. Her thoughts about God, evolution, and the quantum realm fascinated me such that I went right to Amazon and bought three of her books. This morning I started in on the first one (The Unbearable Wholeness of Being) and ran across this stunning thought in the introduction:

Raimon Panikkar said that when theology is divorced from cosmology, we no longer have a living God but an idea of God. God becomes a thought that can be accepted or rejected, rather than the experience of divine ultimacy. Because theology has not developed in tandem with science (or science in tandem with theology) since the Middle Ages, we have an enormous gap between the transcendent dimension of human existence (the religious dimension) and the meaning of physical reality as science understands it (the material dimension). This gap underlies our global problems today, from the environmental crisis to economic disparity and the denigration of women.

Ilia Delio, The Unbearable Wholeness of Being, p. xix

She’s going to have to do some convincing for me to accept the conclusion of the last sentence, but the bigger thought that our theology needs to continue to develop along with our cosmology so that they can be coupled in a way that God is more than an “idea” in the modern age is one I’m going to be chewing on for a while. Looking forward to the rest of this book!

The Teaching vs. The Teacher

The last couple days I’ve been reading a book of theology by an author I was heretofore unfamiliar with. I know and trust a couple of the guys who endorsed it, though, so I plowed in and I’m generally enjoying it and on board with what the author has to say. Curious to find out more about him, I headed over to his website, which then pointed me to his Twitter. And what I found there? Oh dear.

This author of a thoughtful book championing love as the highest law has a Twitter account full of vitriol against our current President, frequent retweets of the loudest and most thoughtless conservative pundits, and images comparing vaccine mandates to Nazism. I was stunned by the incongruity. The people I know who endorsed his book (written in 2017) are thoughtful, gentle people who aren’t rabid politically in either direction. So what’s up with this guy? Even more, his website offers the reader a chance to sign up for his “Discipleship Course”. Do I really want to be discipled by someone like that? And, more challengingly, what do I do with his book when his recent demeanor seems so troublesome?

I tweeted briefly about my quandary, and my friend Matt (a teacher who always seems to ask good questions) asked my thoughts about learning from the approach/perspective rather than the person. And that got enough thoughts going that they merited a blog post rather than a tweet thread.

How can or should we separate the teaching from the teacher?

On one hand, Jesus was the only perfect teacher, so literally anyone else that we learn from is going to have issues. And yet there are those who have taught truth whose behavior is so disqualifying that it brings into question the integrity of everything they taught.

That behavior could be unrelated to their teaching or their methods. J. H. Yoder was the classic example of this quandary. It is perhaps easier, though, to think abstractly about an obscure Mennonite ethicist who abused women than it is to consider examples more fresh and prominent in our memory: men like Ravi Zacharias, Bill Hybels, or Jean Vanier. Did (or should have) their behavior have disqualified them from teaching? Absolutely. When we find out about their behavior after absorbing their teaching, how should we reconsider it? That’s hard.

Then we have the case of this author where the behavior directly brings me to question the teacher, because his online behavior seems so out of line with the principles he’s teaching, and because the judgment and logic and reasoning skills he’s displaying on Twitter make me wonder whether I should question the judgment, logic, and reasoning in his book.

Ultimately, I need to evaluate the teaching separately from the teacher. But if I start seeing a pattern where people who teach these things also act that way, I want to factor that in to my evaluation. Correlation isn’t causation… sometimes.

Then there’s the question of discipleship. As a Christian, my aspiration is to be a “little Christ”. If I disciple myself by attending to teachers who are impulsive, caustic, and illogical — even if they are teaching true principles in that way — I shouldn’t be surprised if I learn to be impulsive, caustic, and illogical myself.

But what about the flip side of that? Surely just because a teacher is kind, gentle, patient, loving, and self-controlled doesn’t mean they’re correct, does it? Well… maybe not. But what does Jesus say in Matthew 7?

Are grapes gathered from thorns, or figs from thistles? In the same way, every good tree bears good fruit, but the bad tree bears bad fruit. A good tree cannot bear bad fruit, nor can a bad tree bear good fruit. Every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. Thus you will know them [prophets, teachers] by their fruits.

Matthew 7:16-20, NRSV

In the case of this particular book and author, I think I’m going to end up on the side of agreeing with the book even though the author is problematic. Partly because I think the principles hold up regardless of the teacher, but also partly because there are other teachers I know who are saying the same thing and who provide very compelling examples of living out the fruit of the Spirit and Jesus’ kingdom principles. But am I gonna follow the guy on Twitter to keep learning from him? Nope.

A 'Christian' nation without empathy

In case the tweet gets deleted: an embedded tweet from John Rogers (@jonrog1) saying: “People mocking 1/6 cops’ emotions and Simone Biles Olympic decision really brings home that we’re way past partisan divide and dealing with the fact that somehow, over the last half century, our predominantly religious culture raised a hundred million Americans without empathy.”

This tweet has made the viral rounds in just the past 24 hours, and it’s got me thinking, because I resonate strongly with the message. I have seen it very frequently among the Christian circles—particularly the evangelical Christian circles—that I have lived in my entire life. The disdainful comments about people on food stamps. The anger at immigrants that “won’t learn the language”. Snarky, hateful comments about “the gays”. An insistence that poor mothers should get benefits cut off if they keep having children. And on and on and on.

What makes it more jarring is that these same Christians, when provided with a specific in-person opportunity to show empathy, will almost always respond in very compassionate, empathetic ways. They will give money, make meals, house people, literally give you the shirt off their back. But when talking about a generic “them”, or an individual that they don’t know personally, that sense of compassion and empathy quickly disappears.

Why is this so? Why do we have such a failure of compassionate imagination that when we think of the generic other, we assume the worst and by default make a critique?

As I ponder this question, my mind is drawn to the incongruity that has nagged at me a thousand times in a thousand different sermons and ‘gospel presentations’. Why is it that the same people who will insist that salvation is 100% God’s work, that we are wretched, helpless, despicable people, and that every act is determined by God, will also be the loud voices preaching that you better shape up your life, and that if your sin doesn’t bother you enough, you’d better think hard and long about whether you’re “really saved”? (As if that theological framework would allow that you could do anything about that status, anyway.)

Then I connect a dot or two related to the predominant theme of “the gospel” from that vein of evangelical Christianity: penal substitutionary atonement. Specifically, that God’s wrath against sin is burning so hot that if you (yes, you) don’t accept the gift of salvation He offers, He is right and just and praiseworthy to torture you for all eternity. (Sure, there’s a hint more nuance in the systematic theology books, but this is the way you hear it from the pulpit. And Sunday School. And VBS. And AWANA. And on and on.)

A conundrum

So what happens when an evangelical tries to make all of these line up? Maybe evangelicals, when they look at these “other” people, subconsciously find it easier to live with the belief that God will torture those “other” people eternally if they can point to reasons why those “other” people are bad. They will deserve it, after all—that little Gospel presentation tells me so. After all, there has to be something different between me and them, right? Because even though that Gospel presentation tells me it’s 100% God and 0% me, there has to be something better about me, right? Because otherwise why is it great and good and praiseworthy that God arbitrarily chose to reward me, but to eternally torture millions of others?

An alternative idea…

What if, on the other hand, I understand salvation as being a part of God’s redemptive story for all people and creation? An act of restoration that will, in C. S. Lewis’ words from Narnia, make all sad things become untrue? A cosmic work of reconciliation that will restore right relationships between all living things? And that Jesus’ death was not God punishing God to pay for some select few a penalty that God arbitrarily set in place, but rather was a demonstration of God’s love for all creation, proof that the effects of sin in the world will bring death to even the most undeserving, but that God’s redemptive power is stronger even than death itself?

With that view in mind, might I (who up until very recently claimed to be an evangelical Christian) have more empathy and compassion for those struggling with the effects of a broken world? Might I see them — even the general, “other” them — first and foremost as image bearers in need of restoration? Might I see that the good works I can do to help those in need are not some work of “social justice” at odds with “the gospel” but rather the very foreworking of reconciliation and restoration that Jesus will eventually return to complete?

A closing comparison

Ever since dispensationalism took hold, the evangelical church has looked askance at themes of environmental care. Not everyone would say it so bluntly, but the underlying theme is something like this: if it’s all going to burn eventually anyway, why does it matter so much if we take care of it? It doesn’t feel like a stretch to think that for many, the same principle might unconsciously apply to the general “other” person: if they’re going to burn in hell for eternity anyway, why should we care now?

May the church repent and return to compassion, empathy, and care for everyone who God loves — which is to say, for everyone.