Category: Richard Beck

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

Richard Beck on loving Christianity (and really, loving certainty) more than loving Christ

It’s been a while since I’ve linked a Richard Beck post, but man oh man does he nail it today with his observations about young, aggressive converts to Orthodoxy and Catholicism. (I’d venture that in previous years we could’ve said this about “cage stage” Calvinist/Presbyterian converts, too.)

A lot of the negative and aggressive energy inserted into these debates is from men who have become recent converts to Orthodoxy. You might be aware of this trend and it’s impact upon Christian social media. The main take of these Orthodox converts is that every branch of Christianity, from Catholics to evangelicals, is a theological failure. Heretical, even. Only Orthodoxy preserves the one true faith.

This conceit, however, isn’t limited to the very online Orthodox. There are also aggressive Catholics who denigrate Protestantism. And in response to these Orthodox and Catholic attacks, there have arisen aggressive Protestant defenders.

Here’s my hot take. I think many of these loud and aggressive converts are more in love with Christianity than they are with Christ. They love the creeds, the church fathers, the liturgy, the saints, the history, the culture of Christendom, the doctrine, the dogma, the theology, the Tradition. What they don’t seem to love very much is Jesus, as evidenced in their becoming belligerent social media trolls.

But where does the vitriol come from? Beck says it’s “fear, plain and simple”. I think he’s right on this, too.

This is one reason we’re seeing so many young men gravitate away from evangelicalism toward Orthodoxy and Catholicism. As sola scriptura Protestants these young men were raised as epistemic foundationalists. In standing on Scripture they stood on a firm, solid, and unshakeable foundation of Truth. The Bible provided them with every answer to every question. Epistemically, they were bulletproof. They were right and everyone who disagreed with them was wrong. This certainty provided existential comfort and consolation. Dogmatism was a security blanket.

Then they went off to seminary or down some YouTube rabbit hole and discovered that “Scripture alone” was hermeneutical quicksand. Suddenly, the edifice of security began to crumble. Where to turn? Where to find a firm and unassailable foundation? The Tradition! One type of foundationalism (the Bible alone) was exchanged for another (the Tradition). In both cases, the evangelical need for bulletproof certainty remained a constant. There has to be some “correct” place to land in the ecclesial landscape. It’s utopianism in theological dress. But the underlying anxiety curdles the quest. Especially if, once the “one true church” is found, the old evangelical hostility and judgmentalism toward out-group members resurfaces. The underlying neurotic dynamic is carried over. Fundamentalism is merely rearranged. In order to feel secure and safe I need to scapegoat outsiders. Their damnation is proof of my salvation, their heresy confirms my orthodoxy.

Yes to all this. One of the big challenges I’ve found myself facing as I left evangelicalism and joined the Episcopal church is to be ok with the uncertainty; to accept that each tradition has its own foibles and messes. Another Beck post more than seven years ago prompted me to write (among other things) that even the most erudite theologian must be wrong on at least 5-10% of their theology. And if so, then certainty of “rightness” as the (usually unacknowledged) base of my security of salvation is inherently shaky ground.

All these years later I am more convinced than ever that the “conversion” I need isn’t from one denomination or tradition to another, but a conversion from a confidence rooted in my own belief’s rightness to a confidence rooted in God’s love for me and evidenced by my love for Jesus and my neighbor.

Recommended podcast: Chris E. W. Green's Speakeasy Theology

Lately I’ve really been enjoying Bishop Chris E. W. Green’s podcast called Speakeasy Theology. Green is a bishop in the Communion of Evangelical Episcopal Churches and Professor of Public Theology at Southeastern University in Lakeland, FL. Green’s background is Pentecostal, but his move into the CEEC has put him in an interesting place where he is deeply invested in the Episcopal tradition while still embracing a strong Spirit-filled embodiment of faith.

His podcast isn’t particularly fancy or polished. It does have theme music, but generally consists of Green in conversation with one or two others, delving into some aspect of theology and/or practice. I particularly appreciate his humble approach to these conversations. While many podcast hosts and theologians would work to make their own points and push their own agenda, he is very willing to just ask questions and let his guests provoke the conversation in the direction they want to go.

A couple recent episodes that stuck out to me: first, God Is More Exciting Than Anything with Dr. Jane Williams. Dr. Williams talks about loving theology, loving prayer, loving God, and serving the church. Green doesn’t do extensive introductions of his guests on the podcast, so as I listened all I gathered at the beginning is that Dr. Williams is a British professor of theology. As the discussion went on, Green asked some questions about advice on the life of a Bishop, and the impact on the Bishop’s family, and what a Bishop should prioritize, and as he listened to her advice with great esteem, I thought wait, I need to connect some dots here. So I Googled Dr. Jane Williams, and found that in addition to being a professor of theology, she’s been married for more than 40 years to Rowan Williams, the former Archbishop of Canterbury. (Lightbulb!) What stuck out to me about this interview, beside the wonderful conversation and counsel from Dr. Williams, was that she was presented (deservedly) entirely on her own authority and merit, with no reference to her husband. This felt like a beautiful and, sadly, remarkable display of respect by Dr. Green.

The second episode I want to recommend is titled The Difference is Doxological, Green’s conversation with Richard Beck. Beck is a professor of experimental psychology at Abilene Christian University and a long-time blogger. (I’ve read Beck for a long time and blogged about his thoughts frequently enough he has his own tag on my blog.) Beck’s specialty is the intersection between psychology and theology, and his discussion with Green is a wonderful hour wrestling with how we think about the acknowledged work of God in people’s lives vs. the work that God does through the common grace of psychological practice. Beck also talks about his own faith journey of deconstruction and rebuilding, giving his long-time readers like Green and me some good background for his blogging.

I’ve recommended Chris Green’s books here before, and I’m happy to recommend the podcast, too. It’s worth a listen.

You can become more holy by becoming more merciful

Fr. Matt Tebbe is one of my favorite writers at the moment. A former evangelical turned Episcopal priest, Matt has a keen eye for the systems at work in our world and a voice for calling them out clearly. The other day he turned his thoughts to God’s mercy:

You can approach God’s holiness in your sin because God’s holiness moves towards you first. Any suggestion that God can’t look upon you or is far from you or doesn’t want to be with you in your sin: what do we see in Christ?

In him the fullness of God was pleased to dwell. And Christ moves toward- not away- from sinners.

You can become more holy by becoming more merciful: with yourself and others.

In my previous evangelical life, it was always the other direction that was emphasized: God, in his (always his) holiness, is offended by you and your miserable, sinful, inept little self. When Jesus touched a sick person, they said, that sick person must’ve been miraculously healed an instant before Jesus hand actually reached them, because Jesus could never have broken the law by touching a sick person. (Such mental gymnastics!) Then I read Richard Beck say that Jesus was so full of life and health that of course he touched the sick person because Jesus’ life and health overwhelmed and pushed that sickness right out of them.

What a blessing to finally see God’s love and mercy and goodness in a restorative and healing way! And thanks Matt for reminding us of it.

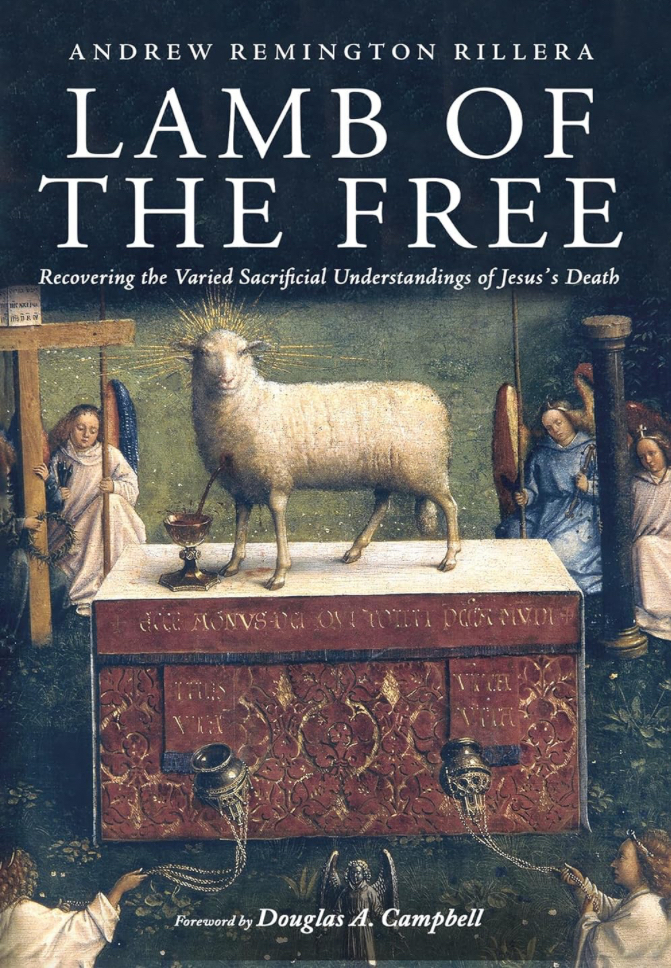

Lamb of the Free by Andrew Remington Rillera

I have a small handful of theological books in my past that I look back on as turning points - books that spoke to me at my particular place and time, opened my eyes, and set my thinking about God in a new direction. The first of those is NT Wright’s Surprised By Hope; the second is Ilia Delio’s The Unbearable Wholeness of Being. I’ll give it a week or two before I inscribe this in stone, but I’m inclined to think that Andrew Rillera’s Lamb of the Free is the next one. Let me try to explain.

In the Protestant church (at least), there has been much ink spilled over the years to systematize atonement theories, that is, to organize all the teaching about Jesus’ death and how it works to save us into some sort of coherent, synthesized framework. In the conservative evangelical world of my first 40 years as a Christian, the predominant, nay, the only acceptable atonement theory is penal substitutionary atonement, usually abbreviated PSA. PSA says that each of us, as a sinner, deserve God’s punishment, but that Jesus died in our place, taking that wrath upon himself. The children’s bibles usually summarize it as “Jesus died so I don’t have to”.

Rillera says that PSA fails to pay attention to how sacrifices worked in the Old Testament, and as such then horribly misreads the New Testament (particularly Paul and Hebrews). This may be the book that inspires me to go back to where I always get bogged down in the Bible In A Year reading plans, and do a close reading of Leviticus.

Rillera starts right off the bat in chapter 1 by making the assertion that

There is no such thing as a substitutionary death sacrifice in the Torah.

He notes that “for sins that called for capital punishment, of for the sinner to be “cut off”, there is no sacrifice that can be made to rectify the situation”, and that far from animal blood on the altar being a substitute for human blood, human blood actually defiled the altar rather than purifying it. Neither was that animal sacrifice about the animal suffering; to maltreat the animal “would be to render it ineligible to be offered to God”, no longer being “without blemish”. Already you can see the distinctions being drawn between this close reading of Levitical sacrifices and the usual broad arguments made in favor of PSA.

Lamb of the Free takes 4 chapters - a full 150 pages - to review OT sacrifices. I’m not going to try to summarize it here. But I have a new understanding and appreciation for paying attention to those details now! Then in chapter 5 he turns the corner to talk about Jesus, and summarizes his arguments thusly:

(1) According to the Gospels, Jesus’s life and ministry operated entirely consistent with and within OT purity laws and concern for the sanctuary.

(2) Jesus was a source of contagious holiness that nullified the sources of the major ritual impurities as well as moral impurity.

(3) Thus, Jesus was not anti-purity and he was not rejecting the temple per se.

(4) Jesus’ appropriation of the prophetic critique of sacrifice fits entirely within the framework of the grave consequences of moral impurity. That is, like the prophets, Jesus is not critiquing sacrifice per se, but rather moral impurity, which will cause another exile and the destruction of the sanctuary.

(5) But, his followers will be able to experience the moral purification he offers.

(6)The only sacrificial interpretation of Jesus’s death that is attributed to Jesus himself occurs at the Lord’s Supper. At this meal Jesus combines two communal well-being sacrifices… to explain the importance of his death. However, the notion of kipper [atonement] is not used in any of these accounts…

There’s a lot there, and Rillera unpacks it through the second half of the book. (I was particularly enthusiastic at his point (2), as it dovetails neatly with Richard Beck’s Unclean, where Beck argues that Jesus’ holiness was of such a quality that indeed, sin didn’t stick to him, but rather his holiness “stuck to”, and purified, other people’s sin and sickness.) Rillera says that Jesus’ death conquered death because even death was transformed by Jesus’ touch, and that Jesus came and died not as a substitution but rather as a peace offering from God to humankind. (His unpacking of Romans 3:25-26 and the word hilastērion was particularly wonderful here.) Jesus’ suffering under sin and death was in solidarity with humankind, and uniquely served to ultimately purify humankind from death and sin. (Really, I’m trying to write a single blog post here and summarize a 300 page book. If you’ve gotten this far and you’re still interested, go buy the book and read it. If you want to read it but it’s too pricy for you, let me know and I’ll send you a copy. I’m serious.)

I’ll wrap this up with a beautiful paragraph from a chapter near the end titled “When Jesus’s Death is Not a Sacrifice”. In examining 1 Peter 2, Rillera says this:

First Peter says that Jesus dies as an “example so that you should follow his steps”. In short, Jesus’s death is a participatory reality; it is something we are called to follow and share in experientially ourselves. The logic is not: Jesus died so I don’t have to. It is: Jesus died (redeeming us from slavery and forming us into a kingdom of priests in 2:5, 9) so that we, together, can follow in his steps and die with him and like him; the just for the unjust (3:18) and trusting in a God who judges justly (2:23; 4:19). This is what it means to “suffer…for being a ‘Christian’” (4:15-16). It does not particularly matter why a Christ-follower is suffering or being persecuted; it only matters that they bear the injustice of the world in a Christ-like, and therefore, a Servant-like manner.

There are a dozen other bits I’d love to share - maybe in another post soon. But for now, I’m thankful for Andrew Remington Rillera and his wonderful work in Lamb of the Free. I’ll be thinking about this for a long time.

Some quick thoughts as I synthesize Beck and Delio this morning...

Richard Beck has a post this week addressing “intellectual problems with petitionary prayer”, or to put the question another way: how does prayer “work”? He critiques a vision of God sitting at a distance from the world and being convinced to reach in and intervene in a Creation that otherwise ticks on autonomously. He calls this the “magic domino theory” - the idea that prayer is to get God to reach in and tip over the magic domino that knocks over other dominos to make things happen.

Beck’s latest book, as I understand it (having read his posts about it but not the book itself) argues for a re-enchanted view of the world. In this post he builds off of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ line that “the world is charged with the grandeur of God”:

God isn’t at a distance. God’s energy and power suffuses creation. Creation isn’t ticking along autonomously, like a machine. Creation is alive and exists in an on-going radical dependence upon God. We are continuously bathed in God’s sustaining light and love, and should God ever look away from us we would cease to be.

Now I love this, but I am also internally screaming “but what does this really MEAN?” After a lifetime in fundamentalist evangelicalism being told to accept a broad disconnect between the reality of creation and the “mystery” of God in it, I need something more tangible.

This is where I appreciate being able to read Ilia Delio alongside Beck. Delio, I think, would agree with Beck’s vision of creation being imbued with God’s presence. But she would then start to talk about what that permeation might actually mean at a level of quantum mechanics. And this is so helpful to me because even though, to adapt Arthur C. Clarke, sufficiently advanced science is indistinguishable from magic, I need to at least conceptually be able to ground that “magic” (or to use Beck’s word, “enchanted”) view of God’s interaction with creation in the real, scientific world somehow.

And even though my understanding of quantum physics is quite limited, Delio’s push to bring theology into discussion with modern cosmology has been a key to my ability to stay within the stream of Christianity. I couldn’t deal any more with the disconnected, capricious, judgmental God that evangelicalism gave me. But that we could personify “God” as a conceptualization of the mysterious relational charge running through the fabric of the universe? That somehow uniquely enlightened and enlivened Jesus of Nazareth? That’s an approach that can unite my head and my heart as I (like everyone else) try to grapple with the mysteries of life.

Did the Emerging Church Fail?

Richard Beck has a series going right now in which he asserts that the Emerging Church movement failed. I’m usually pretty aligned with Beck but I’m not so sure this time.

He defines the Emerging Church by some familiar characteristics:

- Engagement with post-modernism

- Struggle with evangelical doctrinal positions, leading to epistemic humility

- New awareness of liturgy

- An “aesthetic component”, including skinny jeans and a “coffee shop vibe”

That group, Beck argues, “never was able to establish a broad network of churches”, and eventually failed because “evangelism became deconstruction”, and, says Beck, “You can’t build churches upon deconstruction.”

I think Beck is setting up a bit of a straw man here to try to make point he wants to make against deconstruction. But I think there’s an alternate history to Beck’s that comes to a different conclusion.

I think we can see two developments from the Emergent Church of the early 2000s.

First, It’s easy to forget that along with Brian McLaren and Rob Bell, people like Mark Driscoll also came along under the Emergent label. The part of Emergent that went the way of Driscoll took an aggressive posture in their engagement with post-modernism, and rejected epistemic humility, but took up at least some pieces of a new liturgy, and were the exemplars of Beck’s skinny jeans-wearing, beer-drinking, coffee shop vibing “aesthetic component”. In short order they would reject McLaren and Bell’s post-modernism and fall into doctrinal fundamentalism, but they didn’t just disappear as Beck asserts.

Second, Beck severely underplays the movement of many in the Emergent Church into mainstream denominations. Rachel Held Evans famously wrote about “going Episcopal”. Nadia Bolz Weber is ELCA. Scot McKnight became Anglican. Richard Rohr, a Franciscan monk, is the patron saint of the whole movement. Anecdotally, at the less-famous level, I see a steady stream of exvangelicals deconstructing, embracing epistemic humility, rediscovering the historic liturgy, and embracing a more traditional “aesthetic component” by joining high church mainline traditions.

So did the Emerging Church “fail” as Beck suggests? Maybe, if you construct your definitions as narrowly as he does. But look just a little more broadly and you can trace a path from the Emergent deconstructionists of the early 2000s to the exvangelicals of the 2010s and 2020s and into the pews of the mainline. Whether we will bring the mainline to a resurgence or only forestall its demise by a few more decades remains to be seen.

Beck: Nationalism and the search for meaning

Richard Beck, on his Substack today, on American nationalism resulting from the need for deep meaning:

…for most of human history, we achieved deep meaning by a connection with an ancestral people. Our tribe, kin, and clan. These relations gave us a history and roots.

But with the rise of the modern nation state, especially with such a rootless nation of immigrants like America, our identities have become increasingly associated less with a tribe than a state, a flag, a country. I am who I am–I matter, I have worth–because I’m an American.

It’s an easy observation that American nationalism is characterized by pride in the country, but Beck’s piece pushed me to think more about how Americans, and especially Christian Americans, could be helped away from the more vitriolic forms of nationalism by finding more meaning in other parts of their self-identity—perhaps specifically in their Christian faith.

Beck, again:

Without deep meaning Americans achieve self-esteem via the status of the nation. You elevate the stature of the nation and you elevate the worth, value, and dignity of its citizens. Make America great and you make its people great. There is a primal pull here, rooted deep in the limbic system. It’s not abstract, but a raw, visceral ground of dignity.

How can I encourage other Christians to find more deep meaning and identity in their faith instead of (or even more than) their country?

Richard Beck: hermeneutical self-awareness and a neurotic spiritual nightmare

Richard Beck is on a roll this week with a short series on reading the Bible. In Part #1 yesterday he states premise #1: “Interpreting is inescapable.”

Do the hard work of Biblical study, put in the time and effort to explore, but don’t think you can avoid, in the final analysis, the necessity of making a call. So make it.

Today in Part #2 he highlights the terror that can come when the self-awareness of interpretation is paired with a belief that God will judge you if you get it wrong.

Hermeneutical Self-Awareness + Judgmental God = A Whole Lot of Anxiety

I don’t know that I ever verbalized this thought myself, but I think it drove a lot of my study and reading in my 20s and 30s. Here’s how Beck describes it:

Biblical interpretation is so anxiety-inducing because it’s viewed as so high stakes. Your eternal destiny hangs in the balance, so you have to get it right. And yet, given the hermeneutical situation, you lack any firm guarantees you’ve made the right choice. The whole thing is a neurotic spiritual nightmare. In fact, it’s this nightmare that keeps many Christians from stepping into self-awareness to own and admit their own hermeneutics. It’s more comforting to remain oblivious and un-self-aware.

This put me in mind of a piece I wrote a few years ago where, as an aside, I mentioned that I’m certainly wrong about some percentage of beliefs, but I can’t tell you which ones. Turns out I was interacting with a Richard Beck piece in that one, too. So what do you do? How do you get your way out of Beck’s “neurotic spiritual nightmare”?

By reevaluating one of the terms in the equation.

So I told my students, You have to believe that God’s got your back, that, yes, you might make a mistake. But that mistake isn’t determinative or damning. Just be faithful and humble. You don’t have to have all the correct answers to be loved by your Father. Each of us will carry into heaven a raft of confusions, errors, and misinterpretations of Scripture. It’s unavoidable. We will not score 100% on the final exam.

But don’t worry. Let your heart be at rest. God’s got your back.

As I like to paraphrase something Robert F. Capon said in Between Noon and Three: yes, I’m assuming that God is at heart loving and gracious. Because, let’s face it: if God is a bastard, we’re all screwed.

Richard Beck: Political detox for evangelicals

Richard Beck has a wonderful post up today, describing American evangelicalism as “addicted to politics”, with a need to detox. He lists “three simple steps” to get free and sober of the addiction.

1. Do not vote in an election for the next ten years, or even ever again.

Basically, go cold turkey. An evangelical who stops voting is like an addict flushing pills down the toilet or emptying bottles down the sink. Break the connection between God and country.

2. Abstain from or delete social media, cable TV and talk radio.

Stop going to the drug dealers. Avoid the street corners where they are pushing their pills.

3. Invest in an apolitical local ministry that cares for the hurting or marginalized.

Sobriety requires a new lifestyle. So stop haunting the crack houses. Find a service, organization, or ministry in your town that cares for hurting or marginalized people. Invest all the hours you used to spend on social media into looking some hurting person directly in the face. Keep doing that until you know her or his name. And keep going until the names become your friends.

Beck notes that these same steps would be appropriate for politically-addicted progressives, too. I dunno if I’d call them “easy”, but it’s helpful to think about the kind of radical steps that would show the problem were being taken seriously.

Richard Beck on finding Common Cause

Richard Beck has a fantastic post out today reflecting on a passage from Barack Obama’s recent memoir and how materialism affects our ability to find common cause across ideological boundaries. Here’s the Obama quote:

T]emperamentally I am sympathetic to a certain strain of conservatism in the sense that I’m not just a materialist. I’m not an economic determinist. I think it’s important, but I think there are things other than stuff and money and income—the religious critique of modern society, that we’ve lost that sense of community.

Here’s my optimistic view. This gives me some hope that it’s possible to make common cause with a certain strand of evangelical or conservative who essentially wants to restore a sense of meaning and purpose and spirituality…a person who believes in notions like stewardship and caring for the least of these: They share this with those on the left who have those same nonmaterialistic impulses but express themselves through a nonreligious prism.

Barack Obama, from A Promised Land

Beck contrasts Obama’s Christian non-materialistic optimism with the atheistic, materialistic pessimism of Ta-Nehisi Coates. Hope, and a pragmatic politics, says Beck, are rooted in a non-materialistic view of reality.

I have leaned politically left in the past decade but been frustrated by the inability of much of the progressive left to share a hopeful view. Beck’s paragraph here turned a light bulb on for me:

…Obama is correct, there are shared values between the materialists and the non-materialists. And those shared values lead us to think we can share “common cause.” We want to. And we try. All the time. But that “common cause” is perpetually undermined as these values are embedded within two very different metaphysical worldviews. In the non-materialist worldview, grace and hope season hate toward political enemies and impatience with the lack of progress in our lifetimes. Non-materialists can play the long game, graciously and hopefully, because they believe in a long game. By contrast, non-materialists [sic, Beck clearly means ‘materialists’ here], since there is no long game and the winners write the history books, will be driven to hate those who oppose them and become violently impatient in the face of conversation, compromise, and incrementalism. Given the pressing urgency of the Revolution hope and grace are moral failures, each dampening the passions needed to change the world.

This is as good an explanation as I’ve seen for the tension between those two groups on the left. Count me among the hopeful non-materialists.

If you go read Beck’s whole post (which you should), you’ll find he also has a couple rather (to borrow a word from my friend Dan) spicy things to say about conservative evangelicals. While I feel his frustration, I wish he would’ve spelled out his reasoning a little bit more to justify such strong words. It would be fascinating to explore why conservative evangelicals, non-materialists in Beck’s schema, seem to so frequently use the materialist’s political playbook. Of course as frequently as Dr. Beck blogs, that piece may already be on its way.