Category: politics

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

American culture: a 'negative world' for Christianity?

My friend Charles pointed me to an NYT profile of Aaron Renn, a businessman from Indiana who gained attention for framing current American culture as being hostile to conservative Christianity, a “negative world” that developed somewhere around 2016.

Renn lives in Carmel, Indiana, a city he describes as proof that “we can have an America where things still work”. Ruth Graham, the author of the profile, compares it to Mayberry or Bedford Falls. The references seem clear enough: this idyllic community hearkens back to 1950s white middle-class America, a golden age in the minds of conservative Christianity. (Less of a golden age for, say, African Americans.) Carmel is an 80% white suburb in the middle of the 70% white Indianapolis metropolitan area. 95% of its residents are US Citizens. Renn describes this environment as “diversity that works”.

Why 2015?

As a child of evangelicalism who grew up in the 1980s and 1990s hearing that the culture was evil, biased against Christians, and an appropriate target for boycotts and hate, it surprised me that Renn’s viral idea was that the “positive world” phase of America lasted until 1994, and the “neutral world” lasted until 2015. What, in this version of history, was the magic event in 2015 that suddenly made America a negative place for Christians? Oh, of course: Obergefell. Because while Mayberry and Bedford Falls may have had a token minority from time to time, they for sure didn’t have any gay folks.

I have some questions.

The unstated assumptions in Renn’s view are begging to be examined. Is it good for Christians to be the dominant culture and dominant in politics? Does that make for a healthy, Jesus-like faith? Why does a Christian position need to be actively opposed to gay marriage? Why can’t Christians simply live with tolerance of their gay neighbors?

I suspect that Renn’s personal beliefs may be more interesting than the profile lets on. He seems very fond of nice public infrastructure and public funding for special education programs - things that are quite unpopular in the current conservative movement.

It’s not clear from this profile where Renn’s theological sympathies lie. Culturally he seems to be wishing for an Eden free not just from gays but also from boorishness, gambling, legalized drugs, and tattoos. Those issues don’t appeal widely enough to gather steam as a movement. But evangelical Christianity is apparently quick to latch on to the trinity of “sex, gender and race” as touchstones of a “secular orthodoxy” that make America a negative place for Christians.

The theologians quoted in the profile come largely from the neo-Reformed movement. Renn apparently got really into Tim Keller for a while, but concluded that Keller’s approach to culture is “insufficient” for the “negative world”. So now he wants to get more aggressive, pursuing societal and political power in a move he likens to the Hebrews conquering Canaan. It should come as no surprise, then, that Josh McPherson is the first pastor quoted in this profile. McPherson, who is hosting a podcast series to help pastors to minister in Renn’s “negative world”, was a primary disciple of Mark Driscoll, the pugilistic, misogynist church planter from Seattle who preached a gospel of (tattooed) hyper-manliness before eventually blowing up his church in scandal and eventually reemerging as a MAGA Pentecostal in Arizona.

It doesn’t add up.

I wish that Graham’s profile had dug further into some of Renn’s inconsistencies. Consider his opinions on his local town:

Carmel is thriving, in Mr. Renn’s view, because its Republican leaders have focused on things like public safety, low taxes, and excellent infrastructure and amenities, while avoiding the distractions of what he called “extreme ideologies,” like D.E.I. hiring practices or banning gasoline-powered lawn equipment.

How in the world do “excellent infrastructure and amenities” and robust public education (from which Renn’s son benefits) align with the current conservative push to get rid of as much government as possible?

And if I’d had any hair left to pull out, I would’ve lost it at this paragraph:

It is a familiar theme: Things may be bad, but liberals started it. The election of Mr. Trump as president is only possible in “negative world”, Mr. Renn said. In “positive world”, an extramarital affair tanked Gary Hart’s presidential campaign. In “neutral world”, Bill Clinton was damaged by his infidelity but survived politically. In “negative world”, with the safeguards of “Christian moral norms” out the window, it was too late for liberals to make any coherent critique of Mr. Trump’s open licentiousness.

On one hand, his point about the relative political damage of marital infidelity has decreased over the decades. But let’s stop and remember for a moment that Gary Hart and Bill Clinton were attacked by conservative Christian Republicans, claiming moral outrage against the infidelity. Why is it suddenly incumbent on the liberals to muster the moral outrage against Donald Trump?

There is no Mayberry to go back to.

Renn sure seems to want to return to his “positive world”, a utopia where you marry a nice church girl, have 2.5 kids and send them to school on their bikes down perfect sidewalks and trails past manicured lawns and picket fences, but where you don’t have to pay taxes to provide those amenities. A community that’s predominantly white, straight, and Christian, with a few token minorities to let you feel diverse and tolerant, and even fewer gays because you’ve run them off so you can feel righteous.

Just one problem: this utopia has never existed. And in the brief slice of 1950s America that Renn idealizes, the white Christian middle-class paradise was built on the backs of the poor, the minorities, and 95% marginal income tax rates for the wealthy.

Where is Jesus?

Notably absent from Renn’s arguments: any hint of concern about being like Jesus. Renn’s ideal apparently isn’t found in the Beatitudes, the Sermon on the Mount, or the Good Samaritan; rather it’s in Mayberry.

But a Christianity void of Jesus is no more than a moralistic shell designed to reclaim a bygone cultural hegemony. Indeed, the most Jesus-like perspective in the whole piece comes from a Muslim commentator:

…as a member of a religious minority for whom the United States has never been “positive world”, Muslim commentator Haroon Moghul said he did not see neutral- or negative-world occupancy as catastrophic.

“Just because wider society isn’t embracing me or rejoicing over me doesn’t mean I get to lash out in response,” he said. “The culture may be opposed to you, but that doesn’t mean you’re not legally and politically secure.”

Ironically, the new Christian hegemony forming under Donald Trump, praised by Renn, is working to ensure that those whom their culture opposes are in fact not legally or politically secure. Or even financially or physically secure.

I am wearily reminded of the trendy evangelical question from my youth: what would Jesus do?

It’s So Much

I looked at the calendar last Friday in weary disbelief. Trump has only been back in office for less than a week? It felt like much longer. All the weariness and the anger has started to pile up again after a four-year respite. Why can’t all the Republicans see the rank hypocrisy? Why don’t they care? Why did all the principles they taught me for 30 years suddenly go out the window?

There are some differences this time, though, and some lessons I’ve learned along the way that might help this time around.

Community Matters

Eight years ago the majority of my local faith community were Trump supporters, and I was the lonely, frustrated, confused voice in their evangelical wilderness. Near the end of Trump’s first term we left that community. We survived on online faith communities for a couple years before finally finding a supportive local church again. At the Episcopal church we don’t unite around politics, which means we still have Trump supporters in our midst, but we don’t hold onto MAGA principles as cultural norms. Local, weekly solidarity and encouragement makes a huge difference.

Managing my Attention Budget

Social media can be great; it can also be awful. We were not designed to know all the things all the time. In the immortal words of Inigo Montoya: “It’s too much. Let me sum up.” I can and need to budget my attention. Not burying my head in the sand about the chaos and evil that is being perpetrated on us by this administration, but also not listening to every anguished other person on social media reacting to it. I need to make sure that my attention is also drawn to the good, the beautiful, and the lovely. (Maybe that Philippians 4:8 message from my evangelical phase has some application here not in avoiding sin but in managing mentally in a difficult time!)

The Weight of the World

It’s a weird position to be in: as a cisgender, middle-aged white man I should be one of the folks least concerned about the new administration’s policies. If anything, they’re designed to promote and benefit people like me. And yet I’m horrified by so many of the actions they’re taking. I also have dear friends and family members who are not in the regime-preferred demographic and who will be directly affected. And I also want the best for them. And so these things weigh heavily. These issues matter, they must matter. We need to work against tyranny and to respect the dignity of every person. We need to love our neighbor as ourself, and welcome the immigrant and the stranger.

I have no idea how the next four years or the next four decades will play out; whether the fury of executive actions this week will flame out as they run up against organizational inertia and the national reality, or whether the second half of my life will be lived out in a country whose government looks very different than it did for the first half. (Who knew that all the “will you be ready for government persecution?” messages we got in youth group would suddenly become applicable when the Christians took power?) But I am mindful that most people throughout history have lived under governments as or more evil and corrupt than this government is shaping up to be, and those people have managed to live, thrive, even flourish. May it be so for us, in this place and time, as well.

On Killing First and Loving Your Enemies

Last night I finished up reading Rise and Kill First, Ronen Bergman’s extensive history of Israel’s secret services. My friend Matt Burdette pointed me to the book and then gave me his copy to read. (Thanks, Matt!) It was enlightening for me, providing some adult perspective on events that linger vaguely in my childhood memories.

Matt’s comment when recommending the book was how careful the Israelis were about collateral damage. Indeed, Bergman’s sources recount many, many times when an attack on a target was either delayed or cancelled because the strike had the potential of killing wives, children, or bystanders. Regardless of where you fall on the morality of extrajudicial killing, this seems like a bare minimum of circumspection. Which makes Israel’s absolute destruction of Palestine this past year all the more striking in its wanton disregard. I’ll come back to that.

Israel’s history as a modern country is short and Bergman shows how intensely personal the mission of national protection and vengeance was to many early leaders of their security services. (One leader of the Mossad had on his office wall a picture of his grandfather, kneeling at gunpoint before Nazi soldiers, about to be shot. Imagine walking in to work every day and having that set the tone. Phew.) That fresh, personal link can make me sympathetic to the motivation for and justification of the long documented string of murders they committed. And yet I have some hesitancy.

To wade at all into the waters of discussion on the Israeli/Palestinian conflict is a cause for trepidation, but let me see if I can (carefully) arrange a few thoughts about this tragic past century.

First, the persecution and expulsion of Jews from many lands where they had lived for generations, finally culminating in the Nazi-perpetrated Holocaust. Words fail to describe the horror. If any people could or should be forgiven for acts of vengeance, these people could and should.

Then the cycle of violent retribution begins. The Israelis begin their life as a country with the displacement of millions of Palestinians from their generational homes, sending them as refugees into unwelcoming neighboring countries and packing them into small enclaves. This causes Palestinian terror groups to strike back in truly horrible ways. Which in turn causes the Israelis to attack. And the cycle continues. At times over the past few decades it has seemed like peace had a chance to be established. Last year’s Hamas attack on Israel, though, followed by Israel’s unprecedented destruction of the Gaza Strip, leave even the most hopeful observers doubting that change can come.

I, of course, don’t have any good answers here. Both sides have been the victims of displacement and horrors; both sides have committed unspeakably violent acts. Whether one can try to put them in the balance to justify one side or the other is a question for ethicists and philosophers far wiser than me. Regardless, both sides are both victims and perpetrators. A century of an eye for an eye and tooth for a tooth has left far too many toothless and blind. The leaders and fighters on both sides are shaped by generations of unresolved trauma. Things don’t look good.

At the risk of bringing the world’s third major religion into the discussion and making too pat an end to this post: this book and historical reflection make the revolutionary nature of Jesus’ teaching to love your enemies stand out to me in sharp contrast to the natural, justifiable inclinations for revenge. The Christian church throughout history has systemically done a really lousy job of following that teaching. But as individuals of all faiths, it seems to me that the path away from universal toothlessness and blindness starts with being willing to give it a try.

The blessing of the dedicated civil servant

There’s a wonderful long-form profile on the Washington Post right now about Chris Mark, a man who eschewed an opportunity for a upper-class education to (literally) go work in the coal mines, and ended up revolutionizing coal mine safety. (That’s a gift link, so you can read it whether you’re a WaPo subscriber or not.) It’s a compelling story of a man, driven by some complex family dynamics, who found his niche and ended up in a government job where he could follow that interest in a direction that has resulted in countless miners’ lives saved over his career.

The value of experts in government driving regulation gets stated explicitly late in the piece:

Every now and then, however, Chris’s work slipped into public view. His coal mine roof rating was used all over the world and, in his own narrow circles, he was well known. In 2016 — the first year in recorded history that zero underground coal miners were killed by falling roofs — Chris landed in a public spat. He’d seen an article by an economic historian about the history of roof bolts in the Journal of Technology and Culture. The historian wanted to argue that roof bolts had taken 20 years to reduce fatality rates because it had taken 20 years for the coal mining industry to learn to use them. All by itself, the market had solved this worker safety problem! The government’s role, in his telling, was as a kind of gentle helpmate of industry. “It was kind of amazing,” said Chris. “What actually happened was the regulators were finally empowered to regulate. Regulators needed to be able to enforce. He elevated the role of technology. He minimized the role of regulators.”

Government functionaries can be an easy target for criticism, but this profile highlights the key and dedicated role that so many play in today’s society. In my own work I have encountered many Federal Aviation Administration employees who fit a similar profile. They found some particular niche interest related to flying, and they made it their life’s work to make it better and safer. It’s often a thankless job, and on a government pay scale that pales next to what they could likely make in industry.

(As a side note, this is part of what makes Trump’s Project 2025 intentions to politicize the civil service so terrifying: it would eliminate protections on just these dedicated experts to replace them with people who don’t know the topic but who donated to the right political cause. You wanna see the country (literally) crumble? Ditch all the regulatory experts like Chris Mark and replace them with Heritage Foundation interns.)

Rethinking who are "The Normal Ones"? A.R. Moxon nails it.

I really appreciated A.R. Moxon’s weekend post framing up the “Weird” discourse from the past week. (This long-ish excerpt is still really just an excerpt. Worth reading the whole thing.)

Not so very long ago, it wasn’t normal to be trans or gay or even nonconforming to very strict gender roles in any way. It wasn’t normal to be a woman with a powerful job. It wasn’t even normal to be a woman with a paid job of any kind. It wasn’t normal or even legal to be a woman with a bank account. It wasn’t normal to be a woman who could just chart their own way in life, and make their own decisions about their bodies and their lives for themselves. And it wasn’t normal to be Jewish, it wasn’t normal to be Muslim, it wasn’t normal to be Hindu, it wasn’t normal to be an atheist; nor was it normal to be Black, or Asian, or any identity in a category called “nonwhite” that people used without really thinking about it. It wasn’t normal to be chronically sick or disabled, and it certainly wasn’t normal to expect to be treated as a full member of society if your way of being was not normal. And there were many many other ways of being that weren’t normal either. They were different, other—weird.

Some of these ways of being abnormal were permitted to a degree, others were not. They were permitted by The Normal Ones, who had the license to decide what identity was, and to establish the strictures which that identity must remain, outside of which that identity could not stray. And not so very long ago, one of the main requirements for anyone with a “weird” identity who was receiving from license for that identity was that they would agree that The Normal Ones had the right to bestow such a license, because they and only they were truly normal.

It was normal to be white. It was normal to be a Christian. It was normal to be a man with a job, and it was normal to be a woman who was a man’s property. It was normal for children to be viewed as property of the parents, which (see previous point) meant the property of the man. It was normal to be straight and cis. It was normal to be able-bodied and employed. More importantly, though, these were the only normal things to be. To not be those things was to be abnormal, and to be abnormal was to be at the mercy of The Normal Ones.

Abuse—by those who were normal, of those who were not normal—used to be normal, and not ever acknowledging how all the most normal forms of abuse actually were abuse was most normal of all. It was perfectly normal to be racist, misogynist, a religious bigot, as a way of defending and maintaining normalcy, which was a way of defending who did and who did not have the right to make decisions about what identities would be permitted, and to what extent the permission would be allowed. So rape was normal, and bigotry was normal, and exclusion and threats and punishment and murder of those who committed the offense of trespassing the established boundaries of what ways of being human would be permitted by normal people was normal.

I fooled you. All of that is still normal. But increasingly, more and more of us are moving on from all that. We’re done with it.

Imperfectly, to be sure, haltingly, no doubt. Sometimes it feels as if we’ve been scaling a mountain face and only recently passed through some clouds, allowing us a view, previously obscured, of what lay above—and so the distance we’ve come often only affords us a better view of how much further we have to climb. I know some would like to use the daunting climb looming above us to claim that we haven’t climbed at all. But, if we are attentive and look downward long enough, we can see, peeking through the clouds, the vast prospect of rigid and supremacist normalcy we’ve left behind. We can see all the ways of being a human that used to depend upon normalized bigotry for permission to exist but which now give themselves their own permission to exist, without seeking any other. We can see more and more identities that are now considered normal, and more and more of the abuse that once was granted as normal is now recognized, from loftier vantage, for the abnormal perversion it is.

Preach, brother Moxon, preach.

The reality gap

So Trump was convicted of 34 felonies. This morning I have a distant cousin on Facebook last night complaining about how broken the justice system is. And this morning he’s calling for another Civil War. I’m just not sure how to bridge this reality gap.

First off, as Matt Tebbe so brilliantly put it:

It’s not a miscarriage of justice when

a Black man is choked out in the street

Or a Black woman is killed in her bed

Or a Black man is gunned down running while Black

But it is when a white millionaire is convicted of many felonies.

This is how whiteness works.

That cousin surely didn’t make a lot of noise about the broken justice system after George Floyd was killed, or Breanna Taylor was killed, or Trayvon Martin was killed… I wonder why now?

And secondly, is that cousin really ready to take up his guns and kill people like me because we disagree politically? And because I think maybe the justice system did its job here?

Now I know it’s far easier to grumble on Facebook than it is to do actual work, and I’m willing to bet at this point I’ve been to more political protests in the last 5 years than he has. But I do wonder how we ever bridge the gap here. Are things so irreparably broken that chaos is inevitable? I fear so, but I hope not.

A radicalizing NYPD-Columbia Education

Sam Thielman goes hard in his most recent piece at Forever Wars titled “What Could Be More Radicalizing Than An NYPD-Columbia Education?”

Eric Adams, the ex-NYPD mayor of New York City —who, in keeping with the grand traditions of his old job, probably doesn’t even live in New York—cares deeply about our children. We know this because he told us so. “These are our children,” he told Katty Kay on MSNBC, “and we can’t allow them to be radicalized like children are being radicalized across the globe.”

It is important to Eric Adams that children learn the right lesson at the right time. And so, on the campus of Columbia University, where the Pulitzer Prizes will be awarded today, he deployed platoons of his former colleagues to administer the kind of education New York City’s ruling class prefers.

Worth reading the whole thing. (As is true any time Sam is writing.)

It is amazing to me the level of over-reaction from School Administration and the NYPD, who clearly wanted an excuse to display their power. Fascim, folks. It’s real. It’s not coming; it’s here already.

A. R. Moxon: War or Nothing

A. R. Moxon has a brilliant and brutal essay out today entitled “War or Nothing”, in which he describes a theme beginning in 2001 with the US’s response to the 9/11 attacks and continues all the way through 2020’s George Floyd protests and this year’s pro-Palestinian protests on college campuses. From it he describes “seven laws of living in a war-oriented society”:

- Killing is not only an appropriate answer to killing, it is the only appropriate answer.

- The worst betrayal possible is any opposition to killing.

- The only appropriate answer to killing is not only killing—it must be disproportionate killing.

- Any hypothetical future threat of potential attack justifies the same disproportionate violent response as an actual attack.

- Any killing we do, not matter how indefensible it is, can only ever be self-defense.

- Wanting to wage war makes you correct in a way that overcomes evidence or results or even coherence.

- Killing is the only thing that will keep us safe from killing. Therefore, anyone who opposes killing represents a threat justifying further killing.

He’s not wrong. A taste:

And millions of us, who have been watching since 2001 or even before, can see how framing the apparatus of killing as indistinguishable from safety helps the apparatus of killing, but not how it helps make us safe. We can see how framing a country as indistinguishable from its murderous government helps that government, but not how it helps the country. We can see how framing all a county’s citizens as indistinguishable from its murderous government helps that government, but not how it helps the people. And we can see clearly how framing killing as the only way to bring safety, and any act other than killing as nothing favors those who want to see a world of death, but not how it helps honor the dead or keeps any of the living safe.

Millions of us think the bigger problem might be the killing. It seems to us war as the only option represents the greatest possible failure of human imagination there can be, and our wealth and resources and ingenuity seem to present many other options. Perhaps if we put our heads together, we might think of something else to do, that isn’t nothing but isn’t war, either. And even if many of us are foolish and ignorant about what that something might be, we think that seeking that something is better than not seeking it. And even if many of us are foolish and ignorant, many of us are not, and even those of us who are ignorant fools can see the way the suggestions and solutions presented by those who are not ignorant fools are ignored while those of us who are the most ignorant and the most foolish receive the most attention from our institutions of influence and power, to frame this whole act of imagination as ignorant and foolish.

And even those of us who are ignorant fools can see how this helps promote the ideal of war or nothing, but we don’t see how it helps us find something that is not killing but isn’t nothing, either.

God grant us leaders brave enough to consider responses to killing that aren’t more killing, but aren’t nothing, either.

I'm not claiming any special prescience, but...

I was cleaning up old blog posts here and found this that I wrote back in 2012:

I think it may take the American evangelical church another decade or so to really realize how closely intertwined they are with the Republican party, but my prayer is that the realization hits sooner rather than later. What compounds the issue is that our view of American exceptionalism makes us prideful enough that we are resistant to learn from our brothers and sisters in other parts of the world on the topic.

Little did I expect that, a decade later, the evangelical church would, see it, realize it, and embrace it. God help us.

Billionaire Hoarders and “Charity”

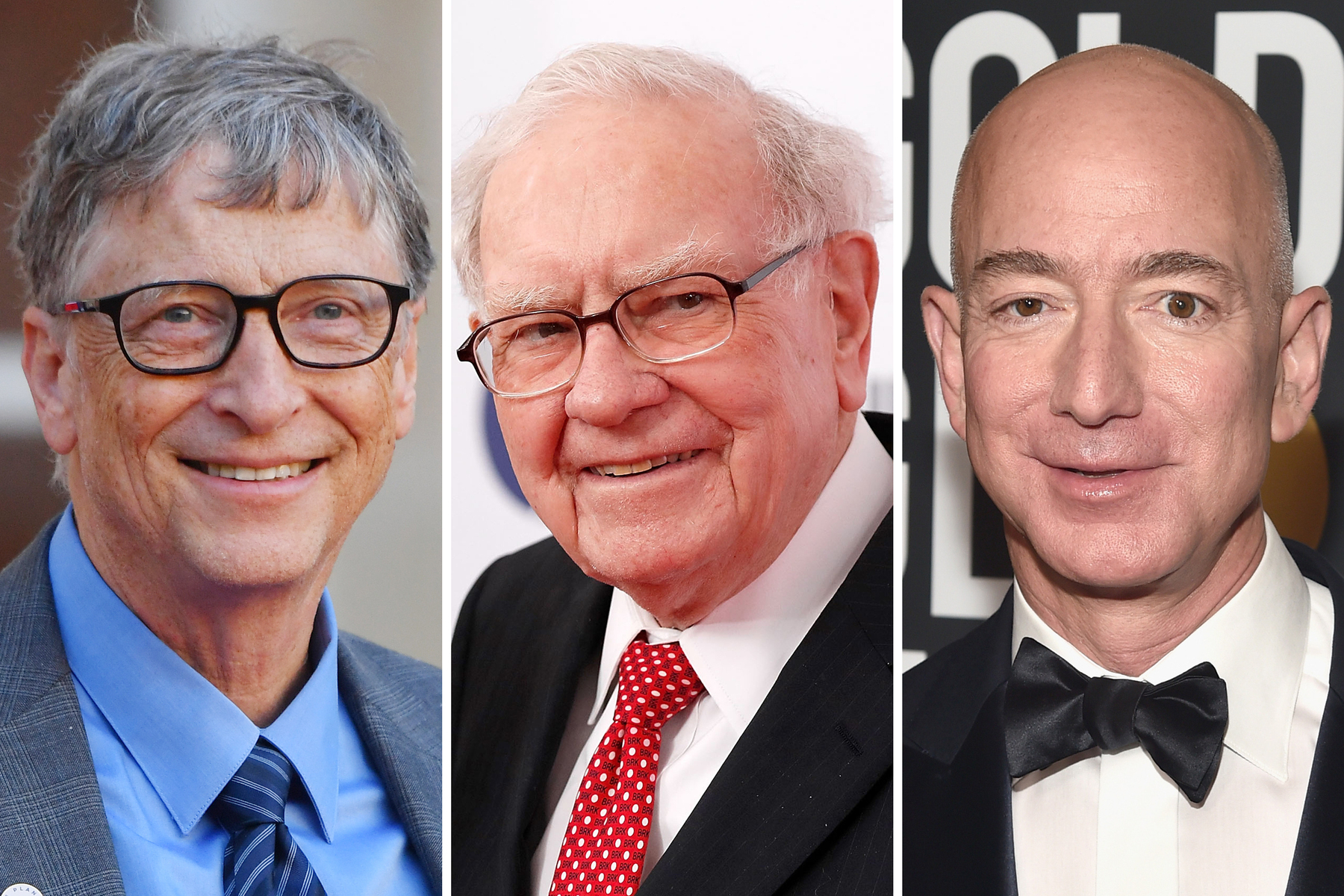

I re-posted a meme to Facebook the other day which suggested that billionaires are “hoarders”, likening them to a “human dragon sleeping on their piles of rubies and gold”. Someone popped up to dispute this characterization, making the following assertions:

- “Billionaires are quite philanthropic. Sure, this is a general statement, but check it out.”

- “The reason billionaires are billionaires is that, generally, they work extraordinarily hard to invest their capital using wisdom while calculating risks.”

Now, there were other assertions and comments, but these two were enough to not pass my smell test. My immediate inclination was that (a) most billionaires aren’t particularly charitable, and (b) most of them have gotten that rich by running exploitive companies - either exploiting natural resources or human beings, or both.

Rather than just go with the smell test, though, I decided to do a first-level investigation and summarize what I found. To do this, I took the Top 10 off the current Forbes 400 list. These guys (and they’re all guys) are all household names, each worth $60B or more. (Yes, that’s billion with a B.) To put $60B in context, if you got $80,000 per day, every day, since Jesus was born, neglecting any inflation or earnings on that money, you would just have gotten to $60B this year. That’s a staggering amount of money.

For each one of these guys I am summarizing their current net worth, reported charitable giving, and how they made their fortune. Spoiler alert: it’s not a pretty picture. Let’s go.

#1: Elon Musk

2022 net worth: $167.6B

Charitable giving: in 2022 he donated $160M, the most ever! Fortune also reports he gave $5.7B to a foundation, but it’s under his control and hasn’t actually been disbursed anywhere yet. That $160M is less than 0.01% of his net worth. Even the $5.7B is only 3% of his net worth… seems unimpressive.

How he made his money: mostly from Tesla. How much his own work and skills contributed to the company’s growth is up for debate, but Tesla and Musk have been sued for running a toxic, discriminatory, abusive workplace on multiple occasions.

#2: Jeff Bezos

2022 net worth: $120B

Bezos has in theory pledged to give his money away, but reports say it’s unclear whether he is actually doing that. The biggest documented donation I saw reported was $100M to Dolly Parton’s foundation. Which, to be fair, is a noble cause, but $100M is only 0.08% of Bezos’ net worth.

How he made his money: Amazon, of course. You don’t have to search far to find multitudes of reports of Amazon’s abusive practices to their employees. Maybe not such a good guy, either.

#3: Bill Gates

2022 net worth: $106B

Credit where credit is due: Gates has already given more than $50B of his fortune to the Gates Foundation, and that Foundation is doing significant work around the world in important causes. Bravo, sir.

How he made his money: Microsoft. As in, he wrote the original MS-DOS, and just managed to hit the wave of computers in an unprecedented and unrepeatable way.

#4: Larry Ellison

2022 net worth: $101B

Ellison reportedly is struggling to figure out how to give his money away. So far his reported donations are all in the $100 - $200M range (0.1% - 0.2% of his net worth). (He apparently found it easier to spend $300M to buy an entire Hawaiian island.)

How he made his money: Oracle databases. And then a lot of big finance and investing.

#5: Warren Buffett

2022 net worth: $97B

Here’s the other bright light on this list. Lifetime Buffett has given away almost $50B, largely to the Gates Foundation. However, his wealth is growing “faster than he can give it away”.

How he made his money: investments. If there’s one guy on this list who meets the “a lot of hard work and wise investing” criteria that my interlocutor set out, Buffett is probably that guy.

#6: Larry Page

2022 net worth: $93B

It is reported that he has funded his foundation to $6B, but most of it is in donor-advised funds for later donation, and while the tax breaks have kicked in now, the money hasn’t actually gone to any good use yet. That same article is touting donations to actual charities in the $100k (yes, that’s a K) range, which is, oh, 0.0001% of his net worth. Color me unimpressed.

How did he make his money: he co-founded a little company called Google. So some of that I’m willing to attribute to just hitting the right tech at the right time, similar to Gates and Ellison. But Google’s money-making methods continue to get nastier every time you look - the incessant ads, the deep user tracking, the toxic YouTube algorithms that are happy to feed you fascist content if it’s what keeps you watching… not particularly honorable.

#7: Sergey Brin

2022 net worth: $89B

Brin has given maybe $1B over the past 10 years to his own foundation (which is beneficial for tax purposes), and of that billion, the biggest chunk, almost $200M has gone to the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s research. A noble cause, yes… but only donating 1% of his net worth over the past 10 years? Peanuts.

How he made his money: He’s the other half of Google. (See #6.)

#8: Steve Ballmer

Net worth: $83B

Ballmer’s foundation breathlessly announced a $217M donation in 2022, which is to say they are going to offer grants on the topic of climate change. That appears to be the biggest chunk Steve has donated anywhere. That’s 0.25% of his net worth, which I guess is a little more than Sergey Brin gave to the Fox Foundation, but still… it ain’t much.

How he made his money: Ballmer was in early following Bill Gates into Microsoft. If only he were so quick to follow in Gates’ footsteps when it comes to giving his money away.

#9: Michael Bloomberg

2022 net worth: $78B

Bloomberg also deserves some credit here. He has donated as much as $14.4 B lifetime (18% of his current net worth) to his personal foundation, and that foundation has actually dispersed significant funds, including $1.7B in 2022. He has also given nearly $3B in donations to his alma mater, Johns Hopkins University.

How he made his money: he started in investing, and then jumped on the integration of computers and investing in the early 1980s. He branched out into other areas of financial market reporting, but then has also taken detours into politics, serving as the mayor of New York City from 2002 - 2013.

#10: Jim Walton

2022 net worth: $58B

In 2019 Walton made his first significant donation to charity - $1.2B to (naturally) the Walton Family Foundation. That Foundation has done some good stuff in Arkansas, so credit where credit is due there. But $1.2B on a net worth of $58B is still only 2% as a donation, which feels paltry.

How he made his money: he inherited it. (As did his siblings, who are #12 and #15 on the Forbes 400 list.) And how does Walmart continue to turn profits? Well, among other things, by mistreating their employees. Wages below the poverty level. Poor working conditions. Unlawful termination. Union busting. Maybe $1B for art and education in Arkansas can assuage your conscience? Jim can only hope so.

Let’s sum up

So, the Top 10. “Quite philanthropic”. “Work very hard” and made admirable business decisions. Really?

“Quite philanthropic” - I think we can safely put that label on Gates, Buffett, and Bloomberg. Many of the others have made pledges that their money will be given away before or at their death, but that isn’t doing anybody any good now. So, 3 out of 10. Not great, Bob!

“Work very hard and made wise business decisions” - I mean, at some level if you want to lionize people playing the capitalism game to come out ahead, by definition these guys have all done that. But if you want to put some sort of moral filter on it, asking whether their gains are well-gotten or not, I think we could safely chalk up Musk, Bezos, Page, Brin, and Walton in the exploitive category. I can’t say I’m very impressed with Ballmer, either, but Microsoft isn’t ugly and predatory in quite the same way that Walmart, Amazon, and Google are.

You do you, Facebook friend, but to my eyes, it’s not a stretch to see these guys as dragons sleeping on piles of gold and gems while 10% of the world lives in extreme poverty.

A little more back-of-the-envelope math

Just for fun, let’s imagine the top income tax bracket from the 1950s (by all accounts, a wonderful time that a lot of people want to go back to) was in place for these guys. That bracket was 91%. And let’s just do the math on their current net worth. All up the wealth of the Top 10 here and it comes out to $994B. Take that times 91% and you come up with $904.5B which would be in the US Treasury. Now, we can quibble about how wisely the US Government spends its money… that’s for another time. But the US budget deficit last year was $1.4T. So, a tax on just the top 10 wealthiest men in the country would take care of more than two-thirds of the deficit. Yes, that’s just for one year. Adjustments still need to be made. But the wealth of these privileged few, even in the scope of the national economy, is, to quote a famous cartoon moose, “antihistamine money”: not to be sneezed at.