Category: music

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

Pictures at an Exhibition for Guitar

I got to know Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition when I was in high school and my piano teacher assigned me The Gnome. I never got it mastered as much as I wanted, but it was such a fun suite to hack my way through. I listened to the orchestral version of it, and love the gong at the end, but overall I still prefer the piano version.

This video, though, has me reconsidering my opinion. Guitarist Kazuhito Yamashita has arranged the entire Pictures suite for guitar and it is amazing. He has captured both the feel and almost all the notes from the piano version. He varies playing techniques to create lovely textures of sound. And while I’m not up on all the modern classical guitarists, I think it’s safe to say that Yamashita has amazing skill.

Bringing joy to people IS bringing glory to God

Crisanne Werner has a lovely essay up on Substack today about her changing understanding of how the experience of music, and specifically playing music, relates to her spirituality as she goes through a sort of deconstruction.

I, too, have had music be a core part of my spiritual experience for most all of my life. As a worship leader in evangelical churches, I have far too many times heard (and probably used) the “audience of One” phrase that Crisanne wrestles with in her essay. But I love where she lands with it:

…music can, and should, bring glory to God. It shouldn’t be manipulated by false humility; it should have an altruistic motivation. But something that didn’t occur to me as a teen/young adult, was that bringing joy to people is bringing glory to God. Using music to evoke emotions that people otherwise wouldn’t have access to is a gift to them. A gift of love. It falls firmly under the umbrella of loving God and loving others. Other people’s music is that same sort of gift to me- my life, especially my spiritual life, is parched without music. And, despite the proliferation of electronic recordings, nothing moves the soul more than an in-person experience. … On that church stage this weekend, I was fully at peace with my motivation of helping the congregation enter beauty and joy. I was at peace with my audience being One plus three hundred.

I met Crisanne at a retreat last fall and quickly learned that beneath her quiet veneer was a depth of brave wisdom just waiting to come out. I’ve so enjoyed reading her Substack this year. What a treat.

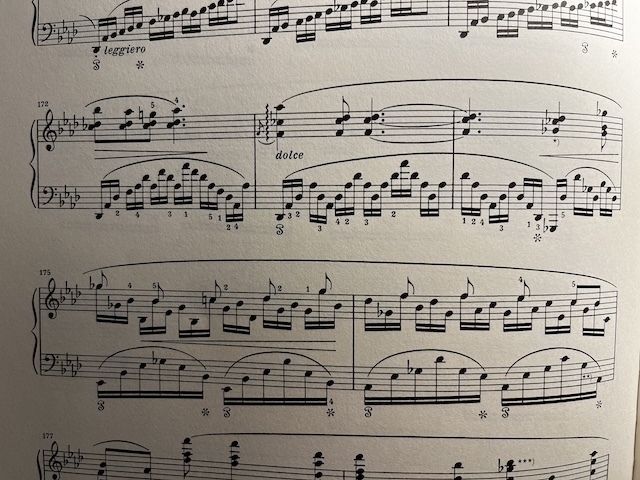

Chopin Being Mean

I have hacked through the Chopin Ballades for years now. I started learning the first one in high school, and in adulthood I played through #3 and #4 often enough that I can, well, hack through them. I never spent the time working everything out and polishing; I just kept sight reading until I could blaze through it.

This past week I decided it was time to actually sit down with #4 and work it out more carefully. Today I got to this pictured section which, when sight reading, had always thrown me for a loop. Practicing the right hand by itself, I finally realized what makes it such a pain.

It’s 6/8 time. On the first line, the bass has gone to triplets in each eighth note. Then on the second line, the right hand picks up triplets per eighth, while the left switches to sixteenths. Ok, that’s 3 against 2, no big deal.

But while the right hand is in triplets, the pattern written (as indicated by the eighth notes on the up stems) is a four-note pattern, almost an Alberti pattern. So, you have what is by pattern a four-beat pattern, played as triplets against two in the bass. My brain wants to interpret that as four against two, which is very simple. But it’s not - rhythmically, it’s 3 against 2, but the 3s are logically and musically grouped in sets of four. This one is gonna take my brain a while to work out.

A Hymn Aptly Chosen

One of the fun things about attending a church in a new and unfamiliar tradition is that things that may be common, old hat, or even tiredly predictable to lifelong participants in the tradition are new and can bring delight to us newbs.

Current example: yesterday morning I thumbed through the worship booklet before the service and saw that the gospel hymn was familiar: Eternal Father, Strong to Save. I know this one primarily as “The Navy Hymn”, could probably sing the first verse from memory, but I’m not sure I’ve ever sung it in church before. A bit of an odd choice, I thought, but it’s at least fun to sing.

And it was, indeed, fun to sing. It’s in a good range, it’s got some fun harmonic progressions, and for being a small and older congregation, there are still some good harmony singers belting it out.

Then the deacon started into the gospel reading and suddenly the reason for the song selection became very clear.

Immediately he made the disciples get into the boat and go on ahead to the other side, while he dismissed the crowds. And after he had dismissed the crowds, he went up the mountain by himself to pray. When evening came, he was there alone, but by this time the boat, battered by the waves, was far from the land, for the wind was against them. And early in the morning he came walking toward them on the sea. But when the disciples saw him walking on the sea, they were terrified, saying, “It is a ghost!” And they cried out in fear. But immediately Jesus spoke to them and said, “Take heart, it is I; do not be afraid.”

Peter answered him, “Lord, if it is you, command me to come to you on the water.” He said, “Come.” So Peter got out of the boat, started walking on the water, and came toward Jesus. But when he noticed the strong wind, he became frightened, and beginning to sink, he cried out, “Lord, save me!” Jesus immediately reached out his hand and caught him, saying to him, “You of little faith, why did you doubt?” When they got into the boat, the wind ceased. And those in the boat worshiped him, saying, “Truly you are the Son of God.”

Matthew 14:22-33

Well played, Father Brian. Well played.

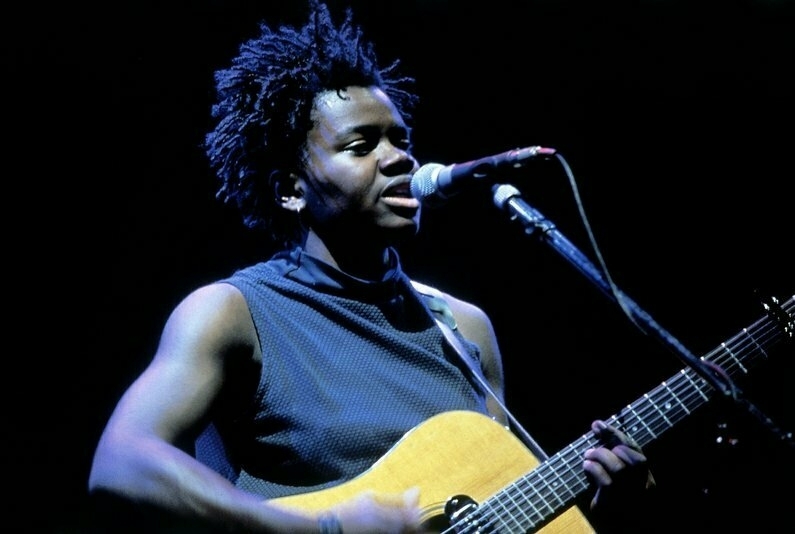

Fast Car, or, why I'm crying at my desk this morning

“You’ve got a fast car, I want a ticket to anywhere…”

If you’ve been a pop music fan at some point in the last 35 years, you’re probably now hearing an acoustic guitar riff in your head. Tracy Chapman’s song Fast Car came out in 1988 and was a Top 10 hit. It’s a wonderful song.

I heard Fast Car for the first time about 3 months ago when a social media post linking to a YouTube of Chapman playing the song in front of a restless crowd at Wembley Stadium came across my feed.

I listened to it, mostly impressed at a 24-year-old enthralling a huge crowd with nothing but an acoustic guitar and a microphone. I was probably doing something else at my desk at the time, and didn’t really listen to the words.

Fast forward to a couple weeks ago when my wife and I were out for a weekend and had dinner on a bar patio listening to a guy play acoustic covers. He played Fast Car. I mentioned to my wife that I’d never really heard the song before a month or two ago. She was incredulous. “You don’t know this song?” It’s about that time in any such conversation that my insecurity and shame creeps in.

I grew up in a fundamentalist homeschooling household where we weren’t allowed to listen to “secular music”. Classical was OK, and the Christian radio station was fine when it played softer stuff (and tolerated when it played “rockier” stuff), but other than that, nope. By the time I was 17 or 18 and had my own car I could turn on whatever radio station I wanted, but by that time the legalism was pretty well engrained in my young soul and my only comfortable dalliance with “secular music” was the old-time country music I played on the piano as part of the impromptu band at Rinky Tink’s ice cream shop during open mic nights.

If you’re my age (mid-40s), all that music you grew up hearing in the late 80s and early 90s? I know none of it. Michael Jackson may as well not exist for me. I was scandalized by my cousin’s U2 Achtung Baby poster, both because it was a “secular” rock band (joke’s on me: they’re probably the most Christian rock band of the last 40 years) and because it had the word “baby” on the poster, which undoubtedly referred to some girl they were interested in, and being interested in girls was wrong until you were old enough to get married.

I was a lonely 12-year-old, and 13-year-old, and heck was just without friends and pretty lonely for a lot of my teenage years. I was 12 years old and desperate enough for help that I called in to donate my own hard-earned funds to the Christian radio pledge drive when the reward premium was Charles Stanley’s book How to Handle Adversity. I anxiously waited for the book to show up, convinced it’d have answers for me. When it finally did, I read what the good reverend from Atlanta suggested: 1) Pray. (Check, been doing that lots.) 2) Lean on friends for support. Well… shit.

I still looked to music to soothe my soul, but the music I listened to as that angsty just-barely-a-teen was music that told me everything would be OK and you shouldn’t really feel sad because God. (Glad’s song Be Ye Glad and Steve Camp’s Love That Will Not Let Me Go come to mind.) There was eventually some CCM music that hinted at it being OK to be angsty - Michael W Smith sang Emily (“on the wire/balancing your dreams/hoping ends will meet their means/but you feel alone/uninspired/but does it help you to/know that I believe in you?”) and then later on a duet with Amy Grant on Somewhere, Somehow (“somehow far beyond today/I will find a way to find you”) - but I felt ashamed to listen to them and feel that way. (They’re still guilty pleasures.)

I signed up for Columbia House Music Club when I was 17 and somehow snuck in a Bryan Adams best of CD. I presume I only knew his name because his Everything I Do (I Do It For You) song was a big enough hit it got played at my (apparently not quite so fundamentalist but still fundy enough we sang Christianized lyrics to Friends in Low Places in chapel) summer camp. Adams’ songs rocked (which I loved) but shocked me and had me feeling bad about listening to them. OK, a song like Kids Wanna Rock was ok because it was just about restless kids. But Run To You was about… sex. We can’t be talking about that, now. Nope. Skip the track.

It took me well into my 20s to finally let myself listen more broadly to “secular” music, my fundamentalist self surprised to find that Bono was a Christian and U2 was singing amazing stuff, that Win Butler was wrestling with his own spiritual ghosts in his songs for Arcade Fire, that it was OK to just enjoy music that wasn’t written about God because it was good music. And in some ways it was fun to have so much music backlog to discover, since aside from Simon and Garfunkel I didn’t really know much of anything of pop music.

But it also means that, for a music guy, I’ve got these big gaps of music knowledge that I’m ashamed of. I try to soak in as much information as I can so I don’t appear to be uninformed, but that façade only lasts so long.

Part of me doesn’t really want to hit publish on this post, because eventually my Dad will read it, and he’ll apologize again. As he’s realized the past couple years how much damage that fundamentalism did to all of us he’s been really broken by it, and apologized over and over. I’ve forgiven him. I’m a dad, too, and have already had to apologize to my kids for the damage that kind of Christianity did to them before I came to my own realization. (I am glad, though, that they’ve grown up with Coldplay and Adele and Arcade Fire and then felt the freedom to find their own music regardless of what genre label it falls under. We’re slowly undoing that mess.) But aside from guilt and forgiveness, I am finding that to start to heal I have to acknowledge the pain of that teenage boy. It was real. It shaped who I am today in a ton of ways.

You got a fast car

I got a plan to get us outta here

I been working at the convenience store

Managed to save just a little bit of money

Won’t have to drive too far

Just ‘cross the border and into the city

You and I can both get jobs

And finally see what it means to be livingYou got a fast car

Is it fast enough so we can fly away?

We gotta make a decision

Leave tonight or live and die this waySo I remember when we were driving, driving in your car

Speed so fast it felt like I was drunk

City lights lay out before us

And your arm felt nice wrapped ‘round my shoulder

And I-I had a feeling that I belonged

I-I had a feeling I could be someone, be someone, be someone

Lyrics from Fast Car by Tracy Chapman

13-year-old Chris would’ve felt every word of this song. Would’ve felt less alone, knowing that other people experienced the same ache. But Chris didn’t get to listen to that song when he was 13. And Chris didn’t stop and really listen to this song until this morning. Which is why 46-year-old grown man Chris is sitting at his desk this morning in tears, listening to Fast Car on repeat.

Podcast Recommendation: A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

For a long time my podcast listening has been almost exclusively nerdy tech podcasts mixed up with nerdy theology podcasts, with an occasional news or true crime mixed in to liven things up. Somehow I have almost entirely bypassed any that were music-related. (I did listen to a couple episodes of Song Exploder right after it debuted, but it just didn’t hook me.)

Somewhere along the line, Rob Weinert-Kendt on Twitter started linking to A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs by British host Andrew Hickey. It took me only a couple episodes and I was hooked.

The format of the podcast is one song per 30-ish minute episode, but each episode covers far more than just the titular song. Hickey provides background on the artist, the influences that formed that artist, stories about the creation of the song, and so on. You come away from the episode having learned a lot not just about a particular song but also about the developing music scene in the Americas (and, once you get in a ways, in Europe). He starts with the first inklings of what would become rock music as they emerged in the big band scene. (Episode 1: “Flying Home” by the Benny Goodman Sextet.)

500 episodes is a significant feat for any podcast, and setting out that goal in the title of your show seems rather ambitious, but I’m willing to bet that Mr. Hickey has all 500 songs charted out, and the moxie to see it through. He’s currently up through Episode 157 (“See Emily Play” by Pink Floyd), and is publishing a lot of bonus material for Patreon subscribers. I’m learning a lot as I go, so even if some interruption keeps the series from completion, it’s still been an excellent investment of time.

So, if you’re interested in rock music, A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs is highly recommended.

Carter Burwell: polymath film composer

I was familiar with Carter Burwell’s name thanks to his score for the Coen brothers’ film True Grit, but I wasn’t aware of the full scope of his film compositions or of his backstory. A brilliant man who just picked up and learned lots of things. Just out of college and trying to make it as a musician while working a lousy warehouse job:

One day, Burwell saw a help-wanted ad in the Times for a computer programmer at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, a nonprofit research institution whose director, James D. Watson, had shared the Nobel Prize in 1962 for discovering the structure of DNA. Burwell wrote a jokey letter in which he said that, although he had none of the required skills, he would cost less to employ than someone with a Ph.D. would. Surprisingly, the letter got him the job, and he spent two years as the chief computer scientist on a protein-cataloguing project funded by a grant from the Muscular Dystrophy Association. “Watson let me live at the lab, and he would invite me to his house for breakfast with all these amazing people,” he said. When that job ended, Burwell worked on 3-D modelling and digital audio in the New York Institute of Technology’s Computer Graphics Lab, several of whose principal researchers had just left to start Pixar.

The Polymath Film Composer Known as “the Third Coen Brother” by David Owen in The New Yorker

His royalties from scoring Twilight funded a house on Long Island, where he lives and works from home, composing on a 1947 Steinway D that came from the Columbia Records studio in New York. “I still fret about having replaced the hammers, but they were worn almost to the wood—some say by Dave Brubeck.”

Worth reading the whole profile.

Rich Mullins - gone 25 years

Rich Mullins died on Sept 19, 1997 in a car accident. A songwriter, poet, and prophet, Rich spoke with a voice that had grabbed my heart as a teenager. Hearing that he had died then ripped my heart right out.

I still remember sitting in church on Sunday morning probably 36 hours later and hearing Pastor Jim (himself a great musician) mention Rich’s death from up front. I was stunned. Leaning forward, I put my face in my hands and tried to grapple with this news while my fiancée put a comforting hand on my back, unsure what to do next.

At some point later that fall I assembled a group of musician friends and put together three of Rich’s songs and got permission to play them in his memory at a college chapel service. I’m sure we didn’t really do justice to “Awesome God”, “Hold Me, Jesus”, or “Elijah” that day, but it felt like the least I could do to honor someone whose music had meant so much to me.

I’ve written about Rich’s music many times here on the blog. The concert summary of the tribute concert at the Ryman, the post where I realized that Rich wasn’t the one playing the piano on all those recordings, and the wistful alternate-universe press release (10 years old already!?!) are perhaps worth revisiting.

Today, though, on the 25th anniversary of his passing, this short clip (shared by Shane Claiborne on Twitter) reminds us Rich’s message remains relevant today.

Rest in Peace, brother, awaiting the resurrection.

Sympathy for Jesus

It had been a long time since I’d listened to this song. Then it came across my playlist this morning. Don Chaffer of Waterdeep in some strange alter ego called The Khrusty Brothers, with his own perspective on being angry at God…

I came stumbling into church with a hot gun in my hands

I was ready to talk to Jesus to tell him my demands

But Jesus ain’t no fool He’s seen this kinda thing before

And He had a couple angels stop me at the front door

I said “now come on that ain’t fair You should be accessible to all”

He said “everybody gets a secretary even just to take their calls”

“So address me to my face If you think you’ve got the balls

But I ain’t playin’ around boy, at all”

This was not what I expected, so I stiffened in my stance

And I tried hard to remember every single shitty circumstance

Then I quivered like a victim with his predator in sight

I was ready now to vindicate, I was ready to start a fight

Now you can stand right there and judge me

Shoot, you can send me straight to hell

I know you got the power I know that fact full well

But before you do explain to me

Why suffering and why death?

And why did I pray all those years

And waste all that good breath?

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Well the angels sang it under their breath by the door

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

I give up, I can’t go on like this any more

“Well I appreciate your kind”, he said and then Jesus poured a drink

My face musta looked funny cause he said, “It’s not like you think”

“I’m saddled with the job you know of interpreting my Dad

To a bunch of frightened people, frightened or just mad

And most of ’em think they got it right” (and then he threw some ice cubes in)

“But most of ’em are just dead wrong about life and death and sin

And then I got my fiancée, she’s supposed to speak my mind

But sometimes she’s just chicken and then she messes it up other times…”

Don Chaffer, Sympathy for Jesus

Waiting for the Lightning

For a guy who loves music, I’ve never been the guy who finds and falls in love with an artist on their first album. From my youth I have tended to find bands on their second or third album - probably the popular one - then gone back and learned their back catalog.

In high school, this meant getting to know Michael W. Smith through Go West Young Man and then backing up to appreciate i2EYE; falling in love with Rich Mullins’ Liturgy, Legacy record and then going back to Never Picture Perfect, and bypassing my brother’s recommendation of Caedmon’s Call until their producer insisted on some highly uncharacteristic horns on the title track of Long Line of Leavers that sucked me in. (Self Titled or 40 Acres? I still can’t decide which is their best record.)

As an adult I wasn’t into Coldplay until X&Y and then belatedly recognized the brilliance of Parachutes and Rush of Blood to the Head. I met U2 via All That You Can’t Leave Behind and still probably don’t sufficiently appreciate Achtung Baby and The Joshua Tree. And then there’s Arcade Fire.

I’m sure I’d heard of Arcade Fire from friends at some point early on. Neon Bible had a lot of buzz in my Twitter follows. Somehow it just never caught my ear. But then The Suburbs came out in late 2010, somewhere in the winter I picked it up on an AmazonMP3 $3.99 sale (remember those days?), and in spring 2011 when I trained for a half-marathon, it was my running music. (Somehow my initial download from Amazon missed the first two tracks, so for a long time I thought the album started with “Modern Man”. Not sure when I realized I was missing songs.)

The albums we really fall in love with are the ones we identify with somehow. When Rich Mullins sang “my folks we were always / the first family to arrive / with seven people jammed into / a car that seated five”, my heart ached in recognition of our own 7-member family adventures in undersized, well used cars. When Andrew Osenga sang “my tiny baby’s breathing / deeper every day / soon she’ll leave her crib forever”, I resonated with the heart of a kindred new father. And when Win Butler lamented “oh, this city’s seen so much / since I was a little child / Pray to God I won’t live to see / the death of everything that’s wild”, mid-30s suburban dad me felt it in my core. The Suburbs burrowed its way into my heart like few albums ever have.

Arcade Fire’s fire burns hot. Band leader Win Butler grew up in Houston. His wife, Régine Chassagne, is from Montreal but has roots in Haiti. He grew up Mormon and majored in religious studies at McGill. They aren’t a “Christian band” and say they don’t really practice religion, but their songs give voice to the Gen X disillusionment with and deconstruction of establishment Christianity that many of us have experienced. In “Here Comes the Night Time”, using the voice of Haitians to reject the legalistic strictures of white Christianity:

They say heaven’s a place

Yeah, heaven’s a place, and they know where it is

But you know where it is?

It’s behind the gate, they won’t let you in

And when they hear the beat coming from the street

They lock the door

But if there’s no music up in heaven,

Then what’s it for?

When I hear the beat

My spirit’s on me like a live-wire

A thousand horses running wild

In a city on fire

But it starts in your feet, then it goes to your head

And, if you can’t feel it, then the roots are dead

And if you’re the judge, then what is our crime?

Here comes the night time

Or in “City With No Children” where the young rebel starts to wonder if he is slowly becoming the establishment:

You never trust a millionaire

Quoting the sermon on the mount

I used to think I was not like them

But I’m beginning to have my doubts

My doubts about it

When you’re hiding underground

The rain can’t get you wet

Do you think your righteousness

Can pay the interest on your debt?

I have my doubts about it

The rock is strong, the band is large, the music sometimes cacophonous, always intense, always pulsating with a righteous intensity.

The Suburbs was nominated for Best Album of the Year at the 2011 Grammy Awards. I remember the currents in my Twitter stream from those of us who knew and loved the band. They were up against Eminem, Lady Gaga, Katy Perry, Lady Antebellum… there was no way they could win. Was there?

Barbra Streisand and Kris Kristofferson announced the award and clearly had no idea, reading the award card, whether The Suburbs was the name of the band or the album. But there it was, Album of the Year.

The band had been backstage, getting ready to play a song to close the show. They came out, accepted their Grammy, then Win set it down on his amp and away they went with “Ready to Start”. Always live, always real, always ready to play.

In 2014 they went on tour with their new album Reflektor. The novelty for that tour was asking fans to dress up (think evening wear) to attend the show. One week in the fall of 2013, before the album released, I was on a work trip in Montreal and they announced a show at a small club nearby the hotel I was staying at. With only a $10 entry fee. I chose that night to go eat dinner with my co-workers rather than stand in line for a chance to get into the show. I’ve never forgiven myself for that decision. I finally saw them on that tour later in the year at the Target Center in Minneapolis. It was the first and likely last time I’ll ever wear a necktie to a rock concert.

Last week Arcade Fire released WE, their first new record in five years, and their first good one in nine years. (Can we just pretend Everything Now didn’t happen?) Where The Suburbs captured the frustration of 30-somethings realizing the unescapable strictures of the modern world, WE expresses the resistant hope of 40-somethings coming through the COVID era. The Suburbs Arcade Fire were parents of small children; the WE Arcade Fire now see their kids growing up and leaving.

Lookout kid, trust your heart

You don’t have to play the part they wrote for you

Just be true

There are things that you could do

That no one else on earth could ever do

But I can’t teach you, I can’t teach it to you

In “The Lightning I”, the strain of the past decade weighs heavily:

We can make it if you don’t quit on me

I won’t quit on you

Don’t quit on me

We can make it, baby

Please don’t quit on me

I won’t quit on you

Don’t quit on me

I never quit on you

This seamlessly transitions into “The Lightning II”, which brings a weary hope to the middle of tired frustration.

I heard the thunder and I thought it was the answer

But I find I got the question wrong

I was trying to run away, but a voice told me to stay

And put the feeling in a songA day, a week, a month, a year

A day, a week, a month, a year

Every second brings me hereWaiting on the lightning

Waiting on the lightning

Waiting on the light

What will the light bring?

Once again my heart resonates with an artist. . Waiting on the lightning, yes. Hopeful that it will come. And yet shaken enough from the past 5 years of madness to have to ask the question - what will the light bring?