Category: love

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

You can become more holy by becoming more merciful

Fr. Matt Tebbe is one of my favorite writers at the moment. A former evangelical turned Episcopal priest, Matt has a keen eye for the systems at work in our world and a voice for calling them out clearly. The other day he turned his thoughts to God’s mercy:

You can approach God’s holiness in your sin because God’s holiness moves towards you first. Any suggestion that God can’t look upon you or is far from you or doesn’t want to be with you in your sin: what do we see in Christ?

In him the fullness of God was pleased to dwell. And Christ moves toward- not away- from sinners.

You can become more holy by becoming more merciful: with yourself and others.

In my previous evangelical life, it was always the other direction that was emphasized: God, in his (always his) holiness, is offended by you and your miserable, sinful, inept little self. When Jesus touched a sick person, they said, that sick person must’ve been miraculously healed an instant before Jesus hand actually reached them, because Jesus could never have broken the law by touching a sick person. (Such mental gymnastics!) Then I read Richard Beck say that Jesus was so full of life and health that of course he touched the sick person because Jesus’ life and health overwhelmed and pushed that sickness right out of them.

What a blessing to finally see God’s love and mercy and goodness in a restorative and healing way! And thanks Matt for reminding us of it.

You get the feeling from reading them that we might be loved

This old concert recording of Rich Mullins at a Wheaton College chapel service in 1997 is an internet classic, but listening through it again today I was struck by his wisdom about the love of God:

I am at an academic place so I need to speak highly of serious stuff. Although I have trouble with serious stuff, I have to admit, because I just think life’s too short to get too heavy about everything. And I think there are easier ways to lose money than by farming, and I think there are easier ways to become boring than by becoming academic. And I think, you know, the thing everybody really wants to know anyway is not what the Theory of Relativity is. But I think what we all really want to know anyway is whether we are loved or not. And that’s why I like the Scriptures, because you get the feeling from reading them that we might be. And if we were able to really know that, we wouldn’t worry about the rest of the stuff. The rest of it would be more fun, I think. Cause right now we take it so seriously, I think, because of our basic insecurity about whether we are loved are not.

I think you should study because your folks have probably sunk a lot of money into this, and it’d be ungrateful not to. But your life doesn’t depend on it. That was what I loved about being a student in my 40s as opposed to in my 20s is I had the great knowledge that you could live for at least half a century and not know a thing and get along pretty well.

Capon’s Wager on God’s Love

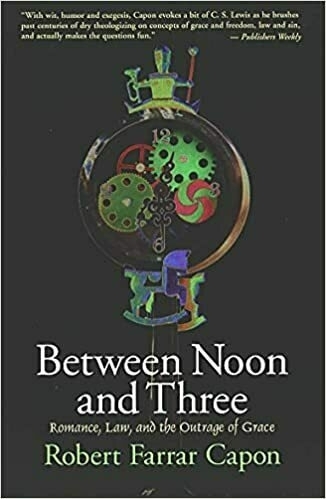

I have on occasion paraphrased something Fr. Robert Capon wrote about God’s love as ”if God is a bastard, we’re all in trouble”. I went digging for the original quote today and came up short of any such choice phrase, but for reference, here’s the longer quote from Between Noon and Three which makes that point, if just a bit less colorfully:

…I have, in this parable, been working only one side of the street — in my effort to do justice to grace, I have neglected justice itself. I am fully aware that in doing so, I have laid myself open to the charge of granting not only screwing licenses but also franchises for far worse things: for pride and prejudice, for torture and exploitation — in short, for getting away with murder.

In my defense, let me point out that Scripture lays itself open to the same charge — and that the other side of the street has been worked so long, so hard, and so often that most people don’t even know there is a sunny side…

But there’s more to it than that. I have expounded Saint Paul to you as saying that not only are we dead to sin but that God is dead to it too — that he has put himself out of commission on the whole subject of blame. And so, indeed, he has: ”I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more.”

I am fully aware that the Scriptures are paradoxical — that God speaks with a forked tongue — and that every lovely thing he says on the side of leniency can be matched by a dozen stringencies that will curl your hair. But I am also convinced that each of us has to make a decision about such utterances. When someone tells you many different things about his attitude toward you, you must first look at him long and long, and decide for yourself whether you care about him at all. But if you finally come to the conclusion that you do care, you must then decide which of his words you will take as his governing word. You ask me why I think God’s leniency governs his severity? Why grace is his sovereign attribute? Well, all I can say to you is that having been a father who has spoken out of both sides of his mouth to six children for twenty-six years — and having all those years believed in a heavenly Father who saves us not by sitting in his penthouse issuing edicts but by sending us the warm, furry body of a Son who drank the nights away with us and died obscurely of the foolishness of it all — all I can say is that I put my bet on the left fork of the tongue. It is my best hope that when my children think of everything I have said and done to them, they choose to remember the times of my severity when I just gave them a kiss on the cheek, poured myself a Scotch, and shut up. And it is my last hope that God hopes the same for himself.

So I really do make no apology for landing on the sunny side of the street. I am sorry if I have offended you; but to me there are some things that simply override everything that comes before or after. And I am sorrier still if you do not feel the same way. For without that ultimate cassation — without that final quashing of the subpoena, that throwing of the prosecution’s case out of court which is the only music there is for the ears of the hopelessly guilty — you and I, Virginia, are simply sunk.

— Fr. Robert F. Capon, Between Noon and Three, Chapter 17