Category: Longform

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

I'm an uncle again!

The congratulations are due to my brother Andrew and his wife Heather on the birth of their second child, and first son, Isaiah David Hubbs. Isaiah was born this afternoon and everyone is doing well.

It’s a bit odd, coming from a family with mostly boys, but Isaiah is my first nephew on either side of the family. Three nieces on my wife’s side, three daughters, and Isaiah’s big sister have equaled out to lots of estrogen. Glad to have this young man to start to restore balance!

Bullet Points for a Thursday

Because hey, I haven’t done one of these on a Thursday for a while.

- It’s been kinda quiet at work this week. Certainly that won’t last.

- Looks like I’m going to make my first trip to Europe in a couple of weeks for some work meetings. Gonna be a lot of flying for two days of work, but it’ll at least cement my frequent flyer status for another year.

- With the cold wet weather all week I have this suspicion we’re gonna go from pseudo-winter to summer without a decent stretch of spring in between. Which is kind of a bummer. I like spring.

- I’m not sure what it is about Stephen Hough’s playing, but I’ve thoroughly enjoyed every record of his that I’ve gotten so far. (I got his new one, “In the Night”, this week. Hyperion has the digital downloads available a couple weeks before the CD drops.) My favorite is still his recording of Rachmaninov’s second concerto, though.

- I’m annoyed that Home Sharing doesn’t work well on iOS7. I wanted to listen to that new Stephen Hough record on my phone in my bedroom last night, and should’ve been able to just hook up to home sharing from my iTunes library on my iMac. However, it stalls out about 80% of the way through the loading process and never actually works. Sounds like it’s a known problem since iOS 5 or so.

- Even with that and a few other gripes with iOS, I have a hard time believing I could be inclined to get some Android phone instead of an iPhone 6 next time I need a phone.

- This fall will be the first time in nearly 15 years of owning a cell phone that I won’t be champing at the bit for my 2-year contract to come up so I can get a new phone because I’m so unhappy with my old one. (I may be champing at the bit if the iPhone 6 is particularly awesome, though. I’d love a bigger screen, and to get a 32GB model instead of the 16GB iPhone 5 I have now.)

Well, that ended up more tech-oriented than I thought it would. Sorry. That’s what you get for random bullet points.

This Time I Can Stay - reflections on the music of a friend

I want to take a little time today to tell you about a guy I know named Andy. (He’s got a weird Dutch last name, so for the purposes of this post I’ll just call him Andy.) Last week Andy announced a fairly major transition in his life (for which I’m very happy for him) and it caused me to reflect on how he’s impacted my life over the last decade. So, forgive a friend a little nostalgia.

If I trace the story I actually end up a little further back than my getting to know Andy. I go back to the early 2000s when I became a fan of a Christian folk rock band called Caedmon’s Call. (My brother had tried to get me turned on to them in the late 90s but, as usual, it took me 5 years to catch up with his musical tastes.) I dug into Caedmons’ music, and got fanboy enough to start participating regularly in an online fan forum. Yeah, I was hooked.

Then came a fateful day in 2001 when Derek Webb, one of the founding members of Caedmon’s Call, announced that he was leaving the group. His replacement? This guy called Andy. Off to the fan forum I went to find out about this Andy guy. Apparently he’d fronted a band called The Normals back in the late 90s - again I was out of the loop. But he had an acoustic record out, so I got it and really dug it. Heck, he even posted in the fan forum every now and again. Very cool.

Fast-forward to fall 2005. I went to see Andrew Peterson play an outdoor show and was crazy excited the night before when I found out that Andy was coming along with him. I blogged about it and even posted a few (pretty scary) pictures. I was on cloud nine.

With summer 2006 came the release of Andy’s record The Morning. With this record I felt like Andy was writing with the voice I wish I could find. Every song hit home with me. I made my first road trip to Nashville to see Andy play a release show for the record.

I followed Andy’s career very closely after that. I drove all over the Midwest to hear him play shows. I set up a fan website. I sponsored a coffeehouse show here in Cedar Rapids. I bummed my way on to a house show road trip he took and rode along with him between a few shows. I hit him up to do lunch when I was in Nashville and hung out at a studio for a couple hours while he recorded vocals. I probably blurred the line between fan and crazy stalker a few times, but in the end I’m pretty sure I can still call Andy my friend.

In the fall of 2011 Andy had another wild idea - a concept album about an astronaut on a long solo trip through space. To make Leonard the Lonely Astronaut really complete, Andy wanted to build a rocket ship set in which to record. I spent another weekend in Nashville with a bunch of friends helping build. The great thing about that weekend is that while it was basically all about (and for) Andy, it helped cement relationships between a bunch of his fans that showed up - guys and gals that continue to be a rich online community even three years later.

Andy’s had a tough few years since the Leonard record came out. A water line broke in his house while he and his family were on a month-long trip and he spent most of the next few months rebuilding. Work was harder to come by. He had the opportunity to tour as a part of Steven Curtis Chapman’s band this past fall which was great for paying the bills but kinda tough on family life. (Andy and his wife have three daughters just a little younger than my own three.)

Two weeks ago Andy had a big announcement. Today (April 30) is his first day as an Artist and Repertoire guy at Capitol Records. It’s a far cry from his indie days - he’ll be working a regular job in a regular office with a salary and benefits and the whole deal. This will keep him from touring much any more, but will have the advantage of a steady income and the opportunity to be home with his family every night.

I couldn’t be happier for Andy in this new phase of his life. Last night he played an online hour-long “concert” from his living room, streaming to fans across the world. (Hey, I know folks from Canada and Brazil who were logged in, so that counts as “the world”, right?) He seemed happier and more relaxed than I’ve seen him in a long while. His daughters flitted in and out of the picture as he sang, at times singing harmony parts to songs they’ve undoubtedly heard a hundred times. It was a beautiful thing.

He finished off the night with a song from his early days with The Normals, called “I’ll Be Home Soon”:

Life it just goes on when the traveler’s gone

And that’s the hardest part, for time has no respect

For a lonely man with a longing heart

‘Cause once you’re where you’ve wanted, everything’s so fast

But I’ll be home soon I’ll be home soon And if you have a place where you belong

You’re a lucky one, for time was meant to waste

A laugh with good old friends or walking hand in hand

I can’t believe I’ll be there and this time I can stay

But I’ll be home soon

I’ll be home soon

I’m a richer man for the music and community that Andy has helped bring into my life over the past decade, but I’m so glad that he now has the opportunity to set some of it aside and just be a husband and a dad. His wife and three daughters will be glad that “I’ll be home soon” is a message they’ll be able to hear every evening around 5:00. We’ll hear more music from him before he’s done. And hey, it’s only a 10-hour drive to Nashville. Next time he plays a local show, I’ll be there.

Thanks, Andy, and blessings on you and your tribe as you start this next phase of your life.

One more Supreme Court amusement

I have some other posts planned, but my buddy Geof pointed out something in a Supreme Court ruling today that made me chuckle.

In Environmental Protection Agency v. EME Homer City Generation, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote a dissent (joined in by Justice Thomas). And Scalia never shies from making pointed opinions.

And it’s (more or less) true! (Scalia quoted Karl Marx, but not directly from the Communist Manifesto.) On page 3 of the dissent (page 40 of the PDF) Scalia says that the “EPA’s utterly fanciful “from each according to its ability” construction sacrifices democratically adopted text to bureaucratically favored policy.”

Now, Scalia wields a deft scalpel, inserting the (unattributed) quote to show even more disdain for the EPA’s action that the majority of SCOTUS affirmed.

As I was paging through the decision to find the reference that Geof mentioned, I also found another reference that amused me: Justice Ginsburg (a very liberal Jewish lady) quoting from the Gospel of John:

Some pollutants stay with in upwind States’ borders, the wind carries others to downwind States, and some subset of that group drifts to States without air quality problems. “The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth.” The Holy Bible, John 3:8 (King James Version)

(From page 8 of the PDF. Apparently the KJV merits a full-blown citation.)

So Scalia quotes Marx, and Ginsburg quotes Jesus. That’s my amusement for the day.

A Serious Argument over a Traffic Stop, or, Why I Love Reading Supreme Court Decisions

One of my secret guilty pleasures (and here you get to plumb the depths of my weird mind) is reading Supreme Court opinions. (I enjoy listening to recordings of the oral arguments, too, but they can get rather dull at times.) I’ve had a fascination with the legal system and particularly the US Supreme Court since I was in high school. I contemplated taking up law as a career path before studying engineering instead, but law continues to fascinate me.

The beauty of the Supreme Court is that by a time a case gets to that level, they’re not dealing with run-of-the-mill principles or with trying to establish facts. The facts have already been established by lower courts, the principles already argued back and forth a couple times in appeals; the USSC only takes on the case when there’s a novel principle to be decided, and when that happens, some of the top legal minds in the country get together to argue the merits.

The thing I enjoy about USSC opinions is that they’re scholarly and dense without being utterly incomprehensible. I’m no legal scholar and undoubtedly don’t get all the case references, but I can sit and read through a 10-page opinion and pretty much understand the gist of the argument, think it over myself, and try to decide which side of the opinion I’d come down on. And sometimes the Justices really get fired up with an opinion, and then the reading gets fun.

But this shouldn’t all be abstract - here’s a recent example.

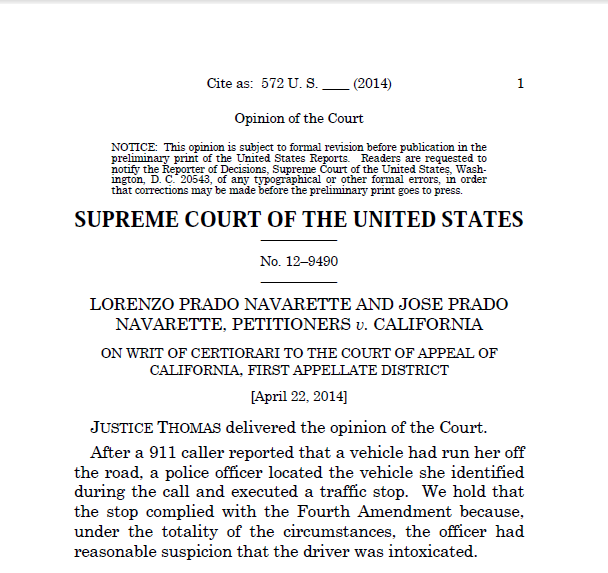

Navarette v. California

Navarette v. California was argued before the Court on January 21, 2014, and the decision and opinions were published April 22 (today as I’m writing this). The case summary and opinions are available on the USSC website, and the headnote for the decision provides a nice summary of the case:

A California Highway Patrol officer stopped the pickup truck occupied by petitioners because it matched the description of a vehicle that a 911 caller had recently reported as having run her off the road. As he and a second officer approached the truck, they smelled marijuana. They searched the truck’s bed, found 30 pounds of marijuana, and arrested petitioners. Petitioners moved to suppress the evidence, arguing that the traffic stop violated the Fourth Amendment. Their motion was denied, and they pleaded guilty to transporting marijuana. The California Court of Appeal affirmed, concluding that the officer had reasonable suspicion to conduct an investigative stop.

So did you get that? We’re arguing here over whether the police had a reasonable suspicion to make a traffic stop and conduct a search. The word “reasonable” is key here, since the 4th Amendment to the US Constitution says, in part, “The right of the people to be secure… against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated…”.

In this particular case, an anonymous 911 caller claimed that a truck “ran the [caller] off the roadway” and reported the truck’s make, model, and license plate number, suggesting that the driver might be drunk. The highway patrol found the truck, followed it for 5 minutes, didn’t see any additional erratic driving behavior, but stopped the truck anyway. When they approached the truck, they smelled marijuana, performed a search, found a bunch of it, and made an arrest.

So there’s the question. Does the Fourth Amendment require an officer who received information regarding drunken or reckless driving to independently corroborate the behavior before stopping the vehicle?

Today the US Supreme Court decided that the answer is yesno. [Whoopsie there! Thanks to _steve in the comment below for correcting me.] Justice Clarence Thomas wrote the majority opinion, which was joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Alito, Kennedy, and Breyer. That opinion runs from page 3 through page 13 of the decision PDF, and it’s not incredibly dense. (It’s also in a narrow-width column so it’s not as long as it sounds.)

Here’s the summary paragraph of the decision:

Like White, this is a “close case.” 496 U. S., at 332. As in that case, the indicia of the 911 caller’s reliability here are stronger than those in J. L. 2, where we held that a bare-bones tip was unreliable. 529 U. S., at 271. Although the indicia present here are different from those we found sufficient in White, there is more than one way to demonstrate “a particularized and objective basis for suspecting the particular person stopped of criminal activity.” Cortez, 449 U. S., at 417–418. Under the totality of the circumstances, we find the indicia of reliability in this case sufficient to provide the officer with reasonable suspicion that the driver of the reported vehicle had run another vehicle off the road. That made it reasonable under the circumstances for the officer to execute a traffic stop. We accordingly affirm.

So that’s not too awful or confusing, right?

Then the fun begins, because you have a dissenting opinion written by arch-conservative Justice Scalia which is joined by the three most liberal members of the court, Justices Ginsburg, Kagan, and Sotomayor. And Scalia, when he gets a little bit wound up, can be entertaining. This one is a prime example.

Here’s how he starts:

Today’s opinion does not explicitly adopt such a departure from our normal Fourth Amendmentrequirement that anonymous tips must be corroborated; it purports to adhere to our prior cases, such as Florida v. J. L., 529 U. S. 266 (2000), and Alabama v. White, 496 U. S. 325 (1990). Be not deceived. Law enforcement agencies follow closely our judgments on matters such as this, and they will identify at once our new rule: So long as the caller identifies where the car is, anonymous claims of a single instance of possibly careless or reckless driving, called in to 911, will support a traffic stop. This is not my concept, and I am sure would not be the Framers’, of a people secure from unreasonable searches and seizures.

Then he starts busting on the arguments.

All that has been said up to now assumes that the anonymous caller made, at least in effect, an accusation of drunken driving. But in fact she did not. She said that the petitioners’ truck “‘[r]an [me] off the roadway.’”.. That neither asserts that the driver was drunk nor even raises the likelihood that the driver was drunk. The most it conveys is that the truck did some apparently nontypical thing that forced the tipster off the roadway, whether partly or fully, temporarily or permanently. Who really knows what (if anything) happened? The truck might have swerved to avoid an animal, a pothole, or a jaywalking pedestrian. But let us assume the worst of the many possibilities: that it was a careless, reckless, or even intentional maneuver that forced the tipster off the road. Lorenzo might have been distracted by his use of a hands-free cell phone… or distracted by an intense sports argument with José… Or, indeed, he might have intentionally forced the tipster off the road because of some personal animus, or hostility to her “Make Love, Not War” bumper sticker. I fail to see how reasonable suspicion of a discrete instance of irregular or hazardous driving generates a reasonable suspicion of ongoing intoxicated driving. What proportion of the hundreds of thousands—perhaps millions—of careless, reckless, or intentional traffic violations committed each day is attributable to drunken drivers? I say 0.1 percent. I have no basis for that except my own guesswork. But unless the Court has some basis in reality to believe that the proportion is many orders of magnitude above that—say 1 in 10 or at least 1 in 20—it has no grounds for its unsupported assertion that the tipster’s report in this case gave rise to a reasonable suspicion of drunken driving.

That’s the USSC version of a smackdown, right there. But he’s not done!

That the officers witnessed nary a minor traffic violation nor any other “sound indici[um] of drunk driving,”… strongly suggests that the suspected crime was not occurring after all. The tip’s implication of continuing criminality, already weak, grew even weaker. Resisting this line of reasoning, the Court curiously asserts that, since drunk drivers who see marked squad cars in their rearview mirrors may evade detection simply by driving “more careful[ly],” the “absence of additional suspicious conduct” is “hardly surprising” and thus largely irrelevant. Whether a drunk driver drives drunkenly, the Court seems to think, is up to him. That is not how I understand the influence of alcohol.'

Thus, says Justice Scalia, “The Court’s opinion serves up a freedom-destroying cocktail consisting of two parts patent falsity.”

I don’t know about anybody else, but I love this stuff. And there’s something great about America when we have some of our greatest legal minds seriously arguing over the legitimacy of a traffic stop.

Goerend: This Session Should Have Been A Blog Post

Russ Goerend is a teacher, relative of a friend, and self-admitted sneaky reader of this blog. He sent me a nice email the other day to introduce himself and say he was a reader, and as a matter of course I went to check out his blog, which I’m going to follow. And right there, just three posts deep, was a post that nailed something that had been bugging me for the past week.

Last week I attended an industry conference in Kansas City. Attendance at this conference was evenly split between industry members and government representatives who regulate us. The goal of the conference was to address regulations as they relate to product approval and flight testing. My twitter stream indicated my frustration during the conference.

Russ nailed a more productive take on a similar problem in his recent post titled “This session should have been a blog post”. Attending a recent education conference session that was designed as lots of quick informational hits, he noted these thoughts:

The issue with that is that the presentation should have been a blog post (SHBABP). Folks who attend a SHBABP session at a conference are missing out on the chance to go deep with someone at the conference. There are quality sessions at every conference that don’t get the audience they should because of SHBABP sessions. I wrote a post the other day about the apps I use on my phone. No one would have flinched if I had submitted that to a technology conference. I could have projected my phone onto a big screen and spent a minute or two on each app. People would have been furiously scribbling the names of the apps as I went. If I was feeling generous, I could have given people time to ask questions. I didn’t submit it to a conference, though. I wrote it as a post, with links to the app store for each app. It’s more useful as a blog post. There are comments for clarification. And, it saves a space in the conference schedule for meaningful conversation.

Bingo.

Too many of the presentations at my recent conference were informational data dumps that would’ve been great - perhaps even more useful - as well-linked blog posts rather than conference sessions. The best conference sessions were ones that provided more original thought and solid Q&A rather than just doing a 45-minute data dump.

Russ proposes an approach to fix this:

So, the challenge. Conference designers: make it known that you will not schedule sessions that should have been a blog post. Feel free to create and publicize a space or hashtag (go ahead and use #SHBABP!) for all your attendees to add and peruse should have been a blog post “session” links. Explain why you’re doing it. Help people understand why you’re holding the session schedule so dear.

Sadly, in my industry there are a couple problems with this approach: 1) the government doesn’t let their folks, even in key positions, publish official blogs. 2) Most of us in industry play our cards too close to our vest to have helpful blog posts, and would likely have to get them officially vetted in a way that would make them impractical.

Still, if I have the opportunity I will encourage conferences to avoid #SHBABP presentations, and will propose presentations that allow for helpful discussion and content rather than just doing a data dump.

Why I'm Leaving the Evangelical Theology blog wars

I’ve had my adventures growing up in the church. In 35 years of church attendance I’ve been a part of a C&MA church, a fundie homeschooling church, two independent Bible churches, two Conservative Baptist churches, and now an EFCA congregation. My family has also been highly influenced by Mennonite and Bretheren folks along the way. We’re an interesting crew.

Let me tell a little bit of my story in order to set things up.

In my mid 20s I was getting involved in leadership at the first church I joined as an adult. Somewhere along the line I got acquainted with Mark Driscoll and started listening through every sermon of his I could find. This led me into what has since been termed the neo-Reformed camp.

One year I went with my pastor to a Desiring God pastor’s conference and heard John Piper, Mark Driscoll, Don Carson, Justin Taylor, and Voddie Baucham. I listened intently as Piper encouraged me to not waste my life, and I still have my Moleskine notebook wherein I hurriedly scribbled Driscoll’s 14 non-negotiable points of the faith. I read C. J. Mahaney’s book on living a cross-centered life and heard his friends tout his credentials to write on humility. I was young, still learning my theology (I’m an engineer, not a pastor!) but had found a place I liked.

But then somewhere along the line things started to change for me.

I read N. T. Wright’s Surprised By Hope and came to realize that the dispensational, Left Behind view of the end times didn’t make as much sense as I had once thought. I read Peter Enns Inspiration and Incarnation and realized that the “literal” reading of the Biblical text wasn’t always the right way to read it. My book pile got overwhelmingly Catholic and Anglican, and the Calvinist I found most winsome ended up being an Iowa essayist named Marilynne Robinson.

I resigned from the church plant I was helping lead because I was completely burned out and had no other way to find rest. I eventually saw that church plant transition to leadership of a young pastor who turned it into a real Acts 29 church plant.

Over the past couple of years I’ve seen a lot of other bits of the system that I once idolized come crumbling down.

I saw Mark Driscoll systematically run out the folks at Mars Hill that disagreed with him, and then spend more money than some of my churches have spent in an entire year’s budget just so he could get “New York Times Bestselling Author” added to his resume.

I saw C. J. Mahaney resign from his denomination over allegations that they covered up child abuse and that he was, ironically, one of the least-qualified people to write a book on humility.

I saw Justin Taylor warn authors against interviewing with a Christian radio host who accused Driscoll of plagiarism, with no word of repentance or apology when her accusations turned out to be correct.

I saw Doug Phillips, the head of Vision Forum (a fundie pro-homeschooling organization) and ministry partner of Voddie Baucham, resign from his ministry after confessing to having an inappropriate relationship with a girl young enough to be his daughter.

What I didn’t see was a lot of public acknowledgment of sin or calls to repentance from those folks surrounding my one-time heroes. The talk was all on the “watch blogs”, where people wrote from perspective somewhere along the spectrum between “godly concern” and “reckless rabble-rousing”. What I did see was a lot of wagons circling, and defensive statements that were factually incorrect and either closed to comment or removed when the comments got loud.

I saw Gospel Coalition teachers define the Gospel in such a way that anyone outside of their little group was probably on the outside looking in. One of Driscoll’s 14 non-negotiables I wrote down that day was penal substitutionary atonement. Al Mohler says that Young Earth Creationism is key. For Wayne Grudem, Owen Strachan, and others in the CBMW, complementarianism is up there at the Gospel level.

What I didn’t see was any acknowledgment that there have historically been various understandings of atonement theory, the age of the universe, the role of women, etc, within the accepted bounds of the church. What I didn’t hear was an acknowledgment that there was a lot of room for negotiables within the bounds of the Apostle’s and Nicene Creeds.

And I’ll be honest: it made me angry.

I’ve spent too much of the last couple years being worked up about these topics. I’ve written angry posts about neo-Reformed Calvinism, young-earth creationism, Biblicism, and gay marriage. And what have I learned? Primarily this:

It’s not worth it.

These online debates have perhaps won me a few cheers but also caused me a few headaches with people within my own church who didn’t understand my attitude or thought I was just trying to cause trouble. They’ve given me a feeling of righteous outrage and truth-telling, but have also helped cultivate in me an attitude of adversarial cynicism that infected my relationship with my own local church.

What it’s taken me a decade to work through and realize is that an awful lot of it is just noise, just hot air. Yes, there are injustices that need to be addressed, but is my blogging actually doing anything productive there? Not really. Does anyone at my church outside of a few of the pastoral staff care about most of these topics or find them worth arguing about? Probably not.

So while it may be exciting to jump on the bandwagon du jour, I’m not sure it’s all that profitable, at least for me right now. There are a lot of other things I can write about and very positive ways to do so. It’s also more peaceful.

So, there are folks I’m unfollowing on Twitter. There are blogs I’m unsubscribing from. There are debates I’m just going to stay out of. And that’s OK.

It’s not that I’m getting less opinionated; I’ll just be sharing my opinions less, and hopefully in more meaningful ways and circumstances. It’s not that I’ll be less upset by injustice and misconduct by church leaders, but instead I’ll stop thinking that my blogging is doing more good for the situation than my praying would be.

Not having the ability to magically make peace for all of America’s evangelical theological battles, I’ll content myself with striving to blessedly make peace and demonstrate love in ways that are meaningful to the people around me. That, for me, is choosing the better part.

To those of you who have been hurt or offended by these posts of mine over the years, my sincere apologies. Let’s talk over coffee sometime soon. I’m buying.

And to those of you who do feel called to continue that sort of blogging, please continue. Go and shout from the rooftops. But also try, as much as it depends on you, to live at peace with all men. Give the benefit of the doubt. Quote accurately instead of selectively.

Loving and defending the innocent and helpless doesn’t mean you always have to be an ass to the oppressor.

That's not me!

OK, I’ve heard stories before about people having their email addresses added to unsavory mailing lists by pranking friends or malicious enemies, but what about the times when someone is apparently unintentionally using your email address for their legitimate purposes? Such is the odd frustration I’ve been dealing with lately.

I’ve had a Gmail account with a username in the format of firstname.lastname@gmail.com ever since Gmail was invite-only. (Remember those days?) It’s worked great for me, though eventually I’ve semi-retired it for email in favor of using Fastmail and an email address based on my personal domain. For the past six months, though, I’ve been getting a string of non-spam emails that appear to be intended for somebody else.

It started out innocuously enough, with a subscription to a mailing list of Cobb County, Georgia first responders. I requested an unsubscribe, and a real person wrote me back, a little confused why I was asking to be removed. I explained and was eventually removed from the list.

But then I started getting other emails. Over the past 6 months or so I’ve gotten the following:

- Royal Caribbean cruise itineraries and payment receipts

- Hudl.com notifications

- Follow-up emails from car dealers saying “thanks for test driving, let’s talk!”

- Survey requests

Then on Monday came the one that made me think about this a little more seriously: an email from LifeLock with the salutation “Dear LifeLock Wallet User:”.

Now, I’m just deleting these emails, but there’s nothing that would prevent me, were I malicious, from going to the websites in question, using the email address (which, remember, is my email address) and the Lost Password routine to set up a new password, and I’d have access to that person’s account.

Which is one level of bad if it’s your hudl.com account (which appears to be some sort of sports training website), but an entirely different level of bad if it’s your credit monitoring service.

What I really don’t understand is how this person continues to make this mistake, when s/he clearly isn’t getting the emails in question. (I have Google 2-factor authentication active on my account, and I track my Google logins closely, so I’m ruling out the thought that this person could be actually getting to those email messages.) If it were you, wouldn’t you start questioning why you weren’t receiving emails, and then eventually correct your mistake?

If this were, say, work email intended for another Chris Hubbs at my employer (such a person used to exist!), it’d be easy enough to look up that person, forward the email to their correct address, and let them know to clarify things with their contacts. But in this case I’ve got very little idea who the right recipient is!

Basically all I can do is say this: if you’re Chris Hubbard from Atlanta, you should be aware that chris.hubbs@gmail.com belongs to a guy in Iowa who would be happy to not keep getting your email. Or if you’re gonna keep sending it to me, at least have the decency to send me the cruise tickets and not just the receipts.

Which artist had the impact?

This interview with Rich Mullins’ producer Reed Arvin is months old now, but I thought of it again the other day and wanted to share one revelation in the interview that particularly impacted me.

[Interviewer:] When I was a kid I would just pour over the liner notes to each of Rich’s albums, and I was always surprised to see how few of the instruments he actually played on the recordings. Obviously, he played the hammered and lap dulcimer, but usually you were the one listed as playing piano and not him. [Arvin:] Rich was incredibly soulful musically but he possessed a particular quality many singer-pianists share: he played all over the instrument, all the time. He was used to accompanying himself, you see. He would hammer out double bass notes even if there was a bass player and things like that. So, when you added other instruments, it didn’t quite mesh. Live, this didn’t make so much difference. But on record, it didn’t really work. Also, he had a very elastic sense of time. Making a record is just a different enterprise. But just to sit around the piano while he played and sang by himself, this was beautiful. And we did that sometimes, just for the pleasure of it.

Rich was the formative artist for me as a musician in my teenage years. I memorized his albums, studied liner notes, learned the piano parts note-for-note, played and sang his songs incessantly.

What somehow never occurred to me while reading the liner notes, that never really hit me until reading this interview, is that maybe I owe Reed Arvin a lot more for influencing my piano style than I owe Rich.

The songs and musical ideas were all Rich’s, so it’s not going to tarnish my view of him and his legacy, but it’s still a surprising thought.