Category: Longform

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

Freedom from the compulsion to pretend: Mtr. Kelli Joyce on gender traditions and the fruit of the spirit

Continuing from yesterday’s post, I want to excerpt one more wonderful section from the conversation between Fr. David W. Johnston and Mtr. Kelli Joyce. This time it’s about ’traditional masculinity’, freedom in Christ, human flourishing, and the Fruit of the Spirit. (Emphasis throughout is mine.)

Johnston: And so what I hear you saying is that for for any any young men who might be watching this, if you want to if you want to go have a beer with your friends and tell jokes, do it unto the glory of God, right?

Joyce: Absolutely. I mean, this is the thing. Jokes are great. Cruelty is not. You can do unfunny cruelty and you can do uncruel jokes, right? A cold one with the bros? Go for it.

Johnston: With any of those things that are traditionally masculine or feminine, like you know, if you like working out or mixed martial arts, I mean, yeah, that’s fine. Love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, self-control.

Joyce: No one thing can get a seal of approval as “that’s good” or “that’s bad”. That’s the whole point of the freedom in Christ: I can’t tell you for sure if beer and jokes are fine because it might be and might not be depending on how you’re doing it, who you’re doing it with, what your relationship to alcohol is, you know, these kinds of things. Same with mixed martial arts or whatever. If you are doing it from a place that is compatible with those fruits of the spirit, do it to the glory of God. And if you’re doing it in some way that is making you less joyful or making you afraid or making you feel insecure, right, then those are things to look at, not because mixed martial arts is bad, right? But because God wants you to have abundant life.

Johnston: From my point of view as somebody who in a lot of ways embodies a lot of very stereotypical uh, masculine traits, still remember like wondering like, well, is there something wrong with me? Cuz I could not care less about cars. I have a son who’s like, “Oh, that’s a cool car.” And I’m like so bored. I’m like, “My favorite car is affordable, predictable, good gas mileage, public transportation.”

…What I see that’s getting coded or trying to Trojan horse into some of that “this is traditional masculinity” is a pass for things that are not the fruit of the spirit. For cruelty, demeaning people, pride, looking at women with lust, you know objects to puff up male pride… I think Christianity does offer us a way of life like you’re talking about, that abundant life. And so that if one wants to embrace very traditional masculinity or femininity, that is okay. And Jesus has shown us what that looks like. Love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, gentleness, self-control.

Joyce: I think that sometimes there is slippage between conversations about what kind of person one may be, is allowed to be, and what kind of person one must be. I think for me the important thing is of course there’s room to like cars, but there’s room to not like cars. The thing that is important is not that one deny interests because they’re masculine or pretend to have them because they’re masculine. Right? Like, what if we could be free of feeling compulsion to pretend in either direction, right? That we don’t like what we do, that we do like what we don’t. What if we were our whole, full, authentic selves, exactly as we were created to be, in relationship, but not competing and not trying to become someone over and against somebody else, just being who we are?

Mtr. Kelli Joyce on the Fruit of the Spirit and gender expression

If you’ve got 45 minutes to listen to a couple Episcopal priests talk about Galatians, the Fruit of the Spirit, and gender expression, by all means spend it on this video:

Fr. David W. Johnston and Mtr. Kelli Joyce have some wonderful thoughts here. There are a couple portions I want to highlight over a couple of blog posts. First, on the “crisis of masculinity” and gender expression, here’s what Mtr. Kelli has to say (36:40 - 39:00 in the video, minor transcript edits for clarity, emphasis mine):

In terms of the crisis of masculinity, it seems like this could be understood almost like how Paul talks about the law. There was this thing that was provided when we needed it, which told us “here’s how you be”. And now there’s freedom, and it’s a freedom we didn’t have before, which is not some new homogenized other way of being that says you have to stop being everything you were, but that says what is important here is that whatever you are is following Christ.

And so I think, to me, I think that there are healthy and Christ-honoring ways of expressing something that looks like traditional masculinity, and healthy and Christ-honoring ways of expressing something that looks very much like traditional femininity. I think that there are sinful and sin-warped ways of doing both of those things. And so what seems important to me is not about pursuing or avoiding a certain kind of gender expression, or restraining that to a certain kind of person or a certain kind of body, but about saying “who has God made me to be?”, “what brings me joy?”, “What feels like I am living out the self I was given by God in creation?”, and “how does that enable me, personally, in my context as who I am, from where I’m standing, to follow Christ?”.

So, to me, there can be virtuous masculinity, virtuous femininity, kind of a virtuous gender neutrality. But the important piece there is the virtue, and not that there is some sort of binding need to have one or the other kind of gender expression. Because nobody has a perfectly anything gender expression. Everybody has traits that are from a mix of these two big categories that we talk about and think about. And that’s OK. In Christ those things are not what define our relationship to God or our relationship to other members of the body. It is who we are together by the power of the Spirit.

Yes and amen.

Choir performance this weekend!

With all the chaos in the world I’m gonna spend some time away from social media this week and blessedly focus on being the best dang tenor I can be in this weekend’s concerts. The Mozart Requiem isn’t gonna sing itself, folks.

I joined the Orchestra Iowa choir last fall when they had an open audition call and I had a little bit of free time. I’ve done all sorts of music stuff in my life but very little actual choir singing, so I was a little bit nervous. But I made it through the audition and it’s been a delightful experience singing with the choir. Maestro Tim Hankewich runs a tight and effective rehearsal, and I’ve never been the best singer in the group but I’m a dang good sight reader (thanks, decades of piano playing!) and I’m not pitchy (thanks, years of listening to my dad tune pianos!).

Tonight we head to the first rehearsal with the orchestra; tomorrow the same; Saturday night and Sunday afternoon we perform. There are still tickets available if you’re in Eastern Iowa and want to attend.

Self-justification is the heavy burden because there is no end to carrying it

Further on in Rowan Williams’ Where God Happens he recounts a saying attributed to the desert father John the Dwarf:

We have put aside the easy burden, which is self-accusation, and weighed ourselves down with the heavy one, self-justification.

That is, as they say, a word. It may seem counterintuitive, he says, but it’s not:

Self-justification is the heavy burden because there is no end to carrying it; there will always be some new situation where we need to establish our position and dig a trench for the ego to defend. But how on earth can you say that self-accusation is a light burden? We have to remember the fundamental principle of letting go of our fear. Self-accusation, honesty about our failings, is a light burden because whatever we have to face in ourselves, however painful is the recognition, however hard it is to feel at times that we have to start all over again, we know that the burden is already known and accepted by God’s mercy. We do not have to create, sustain, and save ourselves; God has done, is doing, and will do all. We have only to be still, as Moses says to the people of Israel on the shore of the Red Sea. [Emphasis mine.]

Williams then takes that individual application and scales it up to the church:

Once again, we can think of what the church would be like if it were indeed a community not only where each saw his or her vocation as primarily to put the neighbor in touch with God but where it was possible to engage each other in this kind of quest for the truth of oneself, without fear, without the expectation of being despised or condemned for not having a standard or acceptable spiritual life. There would need to be some very fearless people around, which is why a church without some quite demanding forms of long-term spiritual discipline—whether in traditional monastic life or not—is going to be a frustrating place to live. [Emphasis mine again]

This put me in mind of a lunch I had with a pastor several years ago. Over chips and salsa I was expressing concern over some area of my life, I don’t remember which, and I despairingly ended up quoting Romans: “should I continue in sin that grace should abound?”

He took a sip of his iced tea, smiled at me and responded “well, that’s generally been my experience, yes.” In generosity of spirit and freedom from fear he encouraged me not with any judgment, but with acknowledgement that he, too, was in need of God’s forgiveness.

This is the fearlessness I aspire to in my own life and interactions with others. Not to diminish the significance of sin, but to acknowledge that no amount of self-justification will suffice to make it right, and that I should put that heavy burden down.

Something has happened that makes the entire process of self-justification irrelevant

I’m reading Rowan Williams’ Where God Happens: Discovering Christ in One Another, and this bit is just beautiful:

The church is a community that exists because something has happened that makes the entire process of self-justification irrelevant. God’s truth and mercy have appeared in concrete form in Jesus and, in his death and resurrection, have worked the transformation that only God can perform, told us what only God can tell us: that he has already dealt with the dreaded consequences of our failure, so that we need not labor anxiously to save ourselves and put ourselves right with God.

The church’s rationale is to be a community that demonstrates this decisive transformation as really experienceable. And since one of the chief sources of the anxiety from which the gospel delivers us is the need to protect our picture of ourselves as right and good, one of the most obvious characteristics of the church ought to be a willingness to abandon anything like competitive virtue (or competitive suffering or competitive victimage, competitive tolerance or competitive intolerance or whatever).”

The Beatitudes (Brian Zahnd Version)

I’m not sure what social media Brian Zahnd is on these days, but he shared his own retelling of Jesus’ Beatitudes on Facebook yesterday and they’re beautiful enough that I’d like to capture them here.

The Beatitudes (BZV)

Blessed are those who are poor at being spiritual,

For the kingdom of heaven is well-suited for ordinary people.

Blessed are the depressed who mourn and grieve,

For they create space to encounter comfort from another.

Blessed are the gentle and trusting, who are not grasping and clutching,

For God will personally guarantee their share as heaven comes to earth.

Blessed are those who ache for the world to be made right,

For them the government of God is a dream come true.

Blessed are those who give mercy,

For they will get it back when they need it most.

Blessed are those who have a clean window in their soul,

For they will perceive God when and where others don’t.

Blessed are the bridge-builders in a war-torn world,

For they are God’s children working in the family business.

Blessed are those who are mocked and misunderstood for the right reasons,

For the kingdom of heaven comes to earth amidst such persecution.

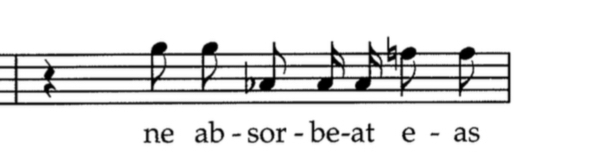

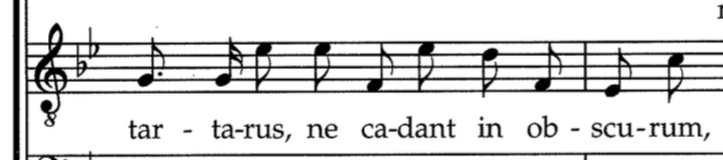

ne cadant in obscurum

I am singing in the Orchestra Iowa chorus for the spring performance of Mozart’s Requiem and we’re in rehearsals right now. And I know this is a hazard of learning and performing music, but I have had this single phrase stuck in my head every day for TWO FULL WEEKS at this point.

Not sure what it is about this particular line. Maybe the bit of time I spent working out in my head that big jump did it… a major seventh is a fun one to navigate, and in this spot the tenors are the only ones singing, so it’s naked and we really need to nail it.

Whatever the reason, I’ll be glad when some other musical phrase supplants this one as my persistent earworm. I mean, I love me some Mozart, but this has been long enough.

Another year of baseball blackouts

So, I’m a Cubs fan and want a streaming option to watch the Cubs games.

As a baseball fan in the US, you have two basic options to watch your team play: get them on a regional sports network usually available through cable or streaming TV, or, subscribe to the MLB.tv streaming package.

MLB.tv

On the face of it, MLB.tv isn’t a bad deal. For $150/year you get access to live streams and replays of all the MLB teams’ games. Oh, but there’s an asterisk: all “out of market” teams’ games. And here’s the fun: if you’re a baseball fan who lives in, oh, Eastern Iowa, there are six, count ’em, SIX MLB teams who count as “in market”. Those teams, and their relative distances from Cedar Rapids, Iowa:

- Chicago Cubs (258 miles)

- Chicago White Sox (255 miles)

- Minnesota Twins (255 miles)

- Kansas City Royals (315 miles)

- Saint Louis Cardinals (289 miles)

- Milwaukee Brewers (233 miles)

That’s right, for $150 per season I can get the privilege of streaming any MLB game as long as that game doesn’t include one of those six teams, notwithstanding the fact that if I want to attend one of those team’s home games I have a MINIMUM FOUR HOUR DRIVE to get there.

Other Options

So, let’s rule out MLB.tv because of their arcane blackout restrictions. The Cubs launched Marquee Network, their own cable TV / streaming channel for just Cubs content, back in 2020. So sure, it’s a regional sports network, right? It should be available on local systems and packages.

Sure, if I want to live in the dark ages and get a cable streaming package from Mediacom, I can pay them $136/month for the privilege. Given their service history around here, that’s a non-starter.

I have two streaming TV options for Marquee Network as a part of live TV streaming providers. Notably, neither of these are top-tier providers (e.g. YouTube TV, Hulu, Sling); they’re also-rans who are either overly expensive (DirectTV Streaming, $107/month) or still expensive and missing other key channels (Fubo, $95/month + “additional taxes & fees”, and doesn’t have TNT, TBS, or Food Network).

I have been a subscriber to Sling, Hulu, and YTTV at various times in the past. I’ve stuck with YTTV for the past few years for the convenience in family profiles and thanks to some package pricing with other Google-based services I subscribe to. But once again in 2025 they have no agreement with Marquee Network, so, no Cubs games that way.

So, What’s a Guy To Do?

That leaves me with really two options:

-

Subscribe to Marquee Network’s streaming service directly. For $20/month I can watch Cubs games live (note: NOT replays, just live games). This is such an inferior option to MLB.tv it’s ludicrous. For basically the same money: ALL THE GAMES + replays (*out of market teams only) on one hand, or only Cubs live games on the other.

-

Just don’t watch the Cubs.

Honestly, I’ll probably end up going with Option #2.

Or as an online acquaintance pointed out this morning, there’s

Option #3: pick another team to cheer for, and make sure that team is out-of-market. He was suggesting the Detroit Tigers. And, I mean, that would work. (It works for me in hockey where my team is the Dallas Stars!) But as a dude in his late 40s it might be time to play the Old Dog/New Tricks card. After 25 years invested as a Cubs fan it’s a habit that’s hard to break.

Come on, MLB, do better.

Opening Day 2025

I don’t remember when I became a baseball fan.

I remember playing teeball when I was in elementary school. I remember my folks taking the family to an Omaha Royals game about that same time. I remember watching parts of the 1985 World Series (Royals / Cardinals) and watching Bret Saberhagen win Game 7 for the Royals to clinch. I was 8.

We moved to Texas when I was 13 and I pretty quickly became a Rangers fan. I listened to so many games on the radio. In the summers when I got really bored I got a baseball scorebook and would keep score while listening to the game. We went to several Rangers games as a family over the years. I remember seeing Nolan Ryan pitch, including in a game where Bo Jackson came up to bat against him. My brother’s friend somehow got tickets to the 1995 MLB All-Star Game and we got the tickets for free as long as I could drive us up to Arlington for the game. (I still can’t believe my mom let us do that.)

When I moved to Iowa I needed a new team. Iowa famously lies in a terrible MLB TV blackout area; there are 6 teams in surrounding states but none of them in Iowa. I could’ve gone any one of several directions, but I fell in with a bunch of Cubs fans, and so a Cubs fan I became.

Cubs fans live by the Dread Pirate Roberts’ credo: “Get used to disappointment.” Save for one shining season in 2016, my 25 years of Cubs fandom has largely been enough winning to keep me motivated to keep up with the team, and then a whole lot of just missing the playoffs or dropping a quick wildcard game and exiting early.

The past several years my tradition has been to wear a Cubs jersey to work on baseball’s Opening Day. As I joke, this is the one day of the year I can be sure that my team has at least a share of first place. This year the Cubs got a head start on opening day with a two-game series in Tokyo against the Dodgers. By the time I got out of bed this morning the Cubs were already losing the game, and I had forgotten to dig out my jersey last night, so I missed the traditional garb. Maybe I’ll dig it out for tomorrow and see if the Cubs can win the second game of the series to at least pull an even record.

Baseball is a beautiful, patient, detailed game, and I’m thankful once again for the occasional hours of respite it provides from the craziness of the rest of the world. Let’s play ball.

American culture: a 'negative world' for Christianity?

My friend Charles pointed me to an NYT profile of Aaron Renn, a businessman from Indiana who gained attention for framing current American culture as being hostile to conservative Christianity, a “negative world” that developed somewhere around 2016.

Renn lives in Carmel, Indiana, a city he describes as proof that “we can have an America where things still work”. Ruth Graham, the author of the profile, compares it to Mayberry or Bedford Falls. The references seem clear enough: this idyllic community hearkens back to 1950s white middle-class America, a golden age in the minds of conservative Christianity. (Less of a golden age for, say, African Americans.) Carmel is an 80% white suburb in the middle of the 70% white Indianapolis metropolitan area. 95% of its residents are US Citizens. Renn describes this environment as “diversity that works”.

Why 2015?

As a child of evangelicalism who grew up in the 1980s and 1990s hearing that the culture was evil, biased against Christians, and an appropriate target for boycotts and hate, it surprised me that Renn’s viral idea was that the “positive world” phase of America lasted until 1994, and the “neutral world” lasted until 2015. What, in this version of history, was the magic event in 2015 that suddenly made America a negative place for Christians? Oh, of course: Obergefell. Because while Mayberry and Bedford Falls may have had a token minority from time to time, they for sure didn’t have any gay folks.

I have some questions.

The unstated assumptions in Renn’s view are begging to be examined. Is it good for Christians to be the dominant culture and dominant in politics? Does that make for a healthy, Jesus-like faith? Why does a Christian position need to be actively opposed to gay marriage? Why can’t Christians simply live with tolerance of their gay neighbors?

I suspect that Renn’s personal beliefs may be more interesting than the profile lets on. He seems very fond of nice public infrastructure and public funding for special education programs - things that are quite unpopular in the current conservative movement.

It’s not clear from this profile where Renn’s theological sympathies lie. Culturally he seems to be wishing for an Eden free not just from gays but also from boorishness, gambling, legalized drugs, and tattoos. Those issues don’t appeal widely enough to gather steam as a movement. But evangelical Christianity is apparently quick to latch on to the trinity of “sex, gender and race” as touchstones of a “secular orthodoxy” that make America a negative place for Christians.

The theologians quoted in the profile come largely from the neo-Reformed movement. Renn apparently got really into Tim Keller for a while, but concluded that Keller’s approach to culture is “insufficient” for the “negative world”. So now he wants to get more aggressive, pursuing societal and political power in a move he likens to the Hebrews conquering Canaan. It should come as no surprise, then, that Josh McPherson is the first pastor quoted in this profile. McPherson, who is hosting a podcast series to help pastors to minister in Renn’s “negative world”, was a primary disciple of Mark Driscoll, the pugilistic, misogynist church planter from Seattle who preached a gospel of (tattooed) hyper-manliness before eventually blowing up his church in scandal and eventually reemerging as a MAGA Pentecostal in Arizona.

It doesn’t add up.

I wish that Graham’s profile had dug further into some of Renn’s inconsistencies. Consider his opinions on his local town:

Carmel is thriving, in Mr. Renn’s view, because its Republican leaders have focused on things like public safety, low taxes, and excellent infrastructure and amenities, while avoiding the distractions of what he called “extreme ideologies,” like D.E.I. hiring practices or banning gasoline-powered lawn equipment.

How in the world do “excellent infrastructure and amenities” and robust public education (from which Renn’s son benefits) align with the current conservative push to get rid of as much government as possible?

And if I’d had any hair left to pull out, I would’ve lost it at this paragraph:

It is a familiar theme: Things may be bad, but liberals started it. The election of Mr. Trump as president is only possible in “negative world”, Mr. Renn said. In “positive world”, an extramarital affair tanked Gary Hart’s presidential campaign. In “neutral world”, Bill Clinton was damaged by his infidelity but survived politically. In “negative world”, with the safeguards of “Christian moral norms” out the window, it was too late for liberals to make any coherent critique of Mr. Trump’s open licentiousness.

On one hand, his point about the relative political damage of marital infidelity has decreased over the decades. But let’s stop and remember for a moment that Gary Hart and Bill Clinton were attacked by conservative Christian Republicans, claiming moral outrage against the infidelity. Why is it suddenly incumbent on the liberals to muster the moral outrage against Donald Trump?

There is no Mayberry to go back to.

Renn sure seems to want to return to his “positive world”, a utopia where you marry a nice church girl, have 2.5 kids and send them to school on their bikes down perfect sidewalks and trails past manicured lawns and picket fences, but where you don’t have to pay taxes to provide those amenities. A community that’s predominantly white, straight, and Christian, with a few token minorities to let you feel diverse and tolerant, and even fewer gays because you’ve run them off so you can feel righteous.

Just one problem: this utopia has never existed. And in the brief slice of 1950s America that Renn idealizes, the white Christian middle-class paradise was built on the backs of the poor, the minorities, and 95% marginal income tax rates for the wealthy.

Where is Jesus?

Notably absent from Renn’s arguments: any hint of concern about being like Jesus. Renn’s ideal apparently isn’t found in the Beatitudes, the Sermon on the Mount, or the Good Samaritan; rather it’s in Mayberry.

But a Christianity void of Jesus is no more than a moralistic shell designed to reclaim a bygone cultural hegemony. Indeed, the most Jesus-like perspective in the whole piece comes from a Muslim commentator:

…as a member of a religious minority for whom the United States has never been “positive world”, Muslim commentator Haroon Moghul said he did not see neutral- or negative-world occupancy as catastrophic.

“Just because wider society isn’t embracing me or rejoicing over me doesn’t mean I get to lash out in response,” he said. “The culture may be opposed to you, but that doesn’t mean you’re not legally and politically secure.”

Ironically, the new Christian hegemony forming under Donald Trump, praised by Renn, is working to ensure that those whom their culture opposes are in fact not legally or politically secure. Or even financially or physically secure.

I am wearily reminded of the trendy evangelical question from my youth: what would Jesus do?