Category: Longform

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

Bullet Points for a Friday

- Between now and July there are only 2 weeks where I’m in the office for 5 full days. This week I was in DC Monday through Wednesday.

- I’m gonna be back in the saddle, er, on the bench as a church musician the next couple weeks. Looking forward to it.

- Pretty dang excited for the concert tickets I bought this week. More on that later.

- Next week I’m out of office for 3 days for Anwyn’s high school graduation.

- This means that by next week at this time we’ll have 2 of our 3 kids out of high school. When did we get old?

- I’ve been helping pick out the hymns for our church services for the past several months, which has been a good way to learn the Episcopal hymnal and also to pick out songs I enjoy singing. Is that self-serving?

- Obviously I mean that I got old but my beautiful wife is as young and lovely as ever.

Happy Friday, everybody.

Because I need more piano music...

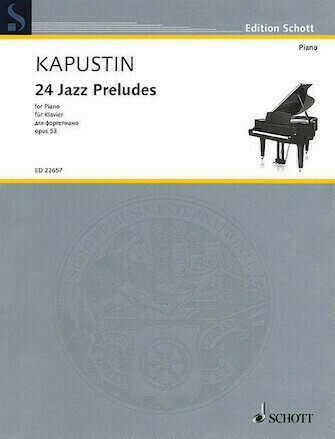

Because I’m a sucker for trying out new piano music that I’ll probably never be good enough to play (or at least to play well), I just ordered this one:

A Russian composer writing jazz-styled preludes? Too much awesome.

Here’s a video of the composer playing one of them:

A radicalizing NYPD-Columbia Education

Sam Thielman goes hard in his most recent piece at Forever Wars titled “What Could Be More Radicalizing Than An NYPD-Columbia Education?”

Eric Adams, the ex-NYPD mayor of New York City —who, in keeping with the grand traditions of his old job, probably doesn’t even live in New York—cares deeply about our children. We know this because he told us so. “These are our children,” he told Katty Kay on MSNBC, “and we can’t allow them to be radicalized like children are being radicalized across the globe.”

It is important to Eric Adams that children learn the right lesson at the right time. And so, on the campus of Columbia University, where the Pulitzer Prizes will be awarded today, he deployed platoons of his former colleagues to administer the kind of education New York City’s ruling class prefers.

Worth reading the whole thing. (As is true any time Sam is writing.)

It is amazing to me the level of over-reaction from School Administration and the NYPD, who clearly wanted an excuse to display their power. Fascim, folks. It’s real. It’s not coming; it’s here already.

I may have become the stereotypical liberal exvangelical.

On a beautiful Sunday morning, I slept in (until 8).

Kicked off the coffeemaker to brew my locally-roasted beans.

Played Wordle. (Got it in 4.)

Read through my email newsletters for the morning. Realized I was long overdue to support A.R. Moxon. Clicked the link and started a monthly donation. By my count, the 5th recovering homeschooled or super-conservative Christian-schooled evangelical-kid-turned-writer I’m supporting. It’s a whole genre.

Made breakfast. Drank coffee. Started reading a book on social science.

I’m now a member of a church where you don’t have to show up at the crack of dawn and stay all morning to prove your devotion to the cause. My wife and kids aren’t going this morning. (My kids don’t usually. My wife has other plans today.) I’ll show up this morning for the 10:15 service and do my part by getting up to read the OT and Psalm. I’ll be home by 11:30. (The Episcopal Church: Where You Can Love Jesus and Your Trans Kid. ™)

After church I’ll probably hit the neighborhood farmer’s market. (First market of the year today!)

Still evangelical enough that there’s a verse in my head to summarize my morning thoughts:

“When the Son sets you free, you will be free indeed.”

Jennifer Knapp: Kansas 25

I was an instant supporter of this album on Kickstarter and now I’m finally getting a chance to listen to it: Jennifer Knapp’s Kansas 25. Back when Kansas came out in 1998, college me was totally drawn in. Smart lyrics, catchy tunes, and a raw honesty that I didn’t hear in a lot of the other Christian music that was on the radio and for sale in the bookstore. I memorized the songs, sang them on my guitar, sang one of them in church, and spun that CD all the time in the car. I have often mentioned it as one of the three “perfect” Christian music albums ever. It’s that good.

Knapp, now 50, has been on a long road since releasing the original Kansas in her early twenties. She moved to Australia in 2002, publicly came out as a lesbian in 2010, recorded some other albums, and became an outspoken advocate for LGBT causes. There’s something incredibly meaningful about hearing her revisit these faith-filled songs in middle age. The miles have taken their toll - the voice is a little more raspy, the tempos a little slower - but the youthful expressions of faith still ring true all these years later.

If you supported the Kickstarter, you probably already have the download. (If not, find it in your inbox!) If you didn’t get in early, head over to Bandcamp where you can preorder it and listen as soon as it officially releases on May 17.

A. R. Moxon: War or Nothing

A. R. Moxon has a brilliant and brutal essay out today entitled “War or Nothing”, in which he describes a theme beginning in 2001 with the US’s response to the 9/11 attacks and continues all the way through 2020’s George Floyd protests and this year’s pro-Palestinian protests on college campuses. From it he describes “seven laws of living in a war-oriented society”:

- Killing is not only an appropriate answer to killing, it is the only appropriate answer.

- The worst betrayal possible is any opposition to killing.

- The only appropriate answer to killing is not only killing—it must be disproportionate killing.

- Any hypothetical future threat of potential attack justifies the same disproportionate violent response as an actual attack.

- Any killing we do, not matter how indefensible it is, can only ever be self-defense.

- Wanting to wage war makes you correct in a way that overcomes evidence or results or even coherence.

- Killing is the only thing that will keep us safe from killing. Therefore, anyone who opposes killing represents a threat justifying further killing.

He’s not wrong. A taste:

And millions of us, who have been watching since 2001 or even before, can see how framing the apparatus of killing as indistinguishable from safety helps the apparatus of killing, but not how it helps make us safe. We can see how framing a country as indistinguishable from its murderous government helps that government, but not how it helps the country. We can see how framing all a county’s citizens as indistinguishable from its murderous government helps that government, but not how it helps the people. And we can see clearly how framing killing as the only way to bring safety, and any act other than killing as nothing favors those who want to see a world of death, but not how it helps honor the dead or keeps any of the living safe.

Millions of us think the bigger problem might be the killing. It seems to us war as the only option represents the greatest possible failure of human imagination there can be, and our wealth and resources and ingenuity seem to present many other options. Perhaps if we put our heads together, we might think of something else to do, that isn’t nothing but isn’t war, either. And even if many of us are foolish and ignorant about what that something might be, we think that seeking that something is better than not seeking it. And even if many of us are foolish and ignorant, many of us are not, and even those of us who are ignorant fools can see the way the suggestions and solutions presented by those who are not ignorant fools are ignored while those of us who are the most ignorant and the most foolish receive the most attention from our institutions of influence and power, to frame this whole act of imagination as ignorant and foolish.

And even those of us who are ignorant fools can see how this helps promote the ideal of war or nothing, but we don’t see how it helps us find something that is not killing but isn’t nothing, either.

God grant us leaders brave enough to consider responses to killing that aren’t more killing, but aren’t nothing, either.

Finished reading: Reading Genesis by Marilynne Robinson

I wasn’t sure what to expect from Robinson writing on Genesis, but I enjoy her writing enough it was definitely something I was going to read. Structured as a narrative commentary, Robinson doesn’t employ chapter breaks or other touchpoints within the text itself. It’s fascinating to read a commentary by a Christian writer who takes the text seriously but not necessarily literally. If there is a broad “point” to her book, it is to feature the uniqueness of Genesis among the Ancient Near Eastern texts, and to highlight the theme of unmerited grace that runs through it. From God’s forgiveness of Cain to Joseph’s forgiveness of his brothers, Robinson tells us that Genesis is set apart from the other ANE texts this way.

I appreciated her book, but didn’t enjoy it as much as reading her essays. I need to pick them up for a re-read.

I'm not claiming any special prescience, but...

I was cleaning up old blog posts here and found this that I wrote back in 2012:

I think it may take the American evangelical church another decade or so to really realize how closely intertwined they are with the Republican party, but my prayer is that the realization hits sooner rather than later. What compounds the issue is that our view of American exceptionalism makes us prideful enough that we are resistant to learn from our brothers and sisters in other parts of the world on the topic.

Little did I expect that, a decade later, the evangelical church would, see it, realize it, and embrace it. God help us.

Medieval Christians' perspective on climate change

Well, this is a fascinating perspective: medievalist Dr. Eleanor Johnson writes on Literary Hub about medieval Christians’ view on climate change:

The Evangelical Declaration on Global Warming opens by saying, “We believe the Earth and its ecosystems—created by God’s intelligent design and infinite power and sustained by His faithful providence—are robust, resilient, self-regulating, and self-correcting, admirably suited for human flourishing.”

As a scholar of medieval religion, culture, and literature, I am utterly perplexed by this belief, because I study a period and region of history where people were, if anything more devoutly and observantly Christian, and I’m here to tell you: medieval English people had no problem believing in climate change and ecosystemic collapse.

Like contemporary Christians, medieval Christians did believe in a providential God. They also believed Nature’s functionality was guaranteed by His will. But they did not believe that, since Nature was underwritten by divine will, Nature would automatically take care of them.

Instead, they assumed that climate change and ecological disasters were divine punishment for human malfeasance. They believed this, first, because they were living through the Little Ice Age, and everyone could feel its effects; nobody bothered to deny it, because it was obviously happening.

A fascinating contrast to today…

Moving my blog to micro.blog

So on a whim I reactivated my micro.blog site and threw 1275 markdown files at it - the entire contents of 20 years of blogging, first on Wordpress, then last year in 11ty. So far, I’m super-impressed. Micro.blog handled the imports and redirects pretty smoothly, has auto-posting to Mastodon and Bluesky, supports emailing, responses, ActivityPub integration… very slick.

I mean, if a week from now I decide it’s not a good fit, I just go change my DNS and point it back at my old domain. But at the moment, this looks like a thing I’ll stick with.