Category: books

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

Recommended reading: Guilt Factories

My brother-from-another-mother Daniel Deboer has a great post up about what he calls “Guilt Factories” that’s worth reading. A snippet:

First you say that grace/faith is all that matters. Then you say that works flow out of grace. Then, as a result of that, you say that what God really cares about is your “heart”. Because if you heart is in the right place, your works are going to be in the right place too.

Then finish it off with a dollop of strictly enforced cultural norms, traditions, and piety. The piety is where it really gets intense, because the grace/faith you’ve been given is supposed to end up in works that are supposed to end up looking exactly like the received norms, the traditions, and the piety.

If you don’t have that piety, you don’t have the works. If you don’t have the works, you don’t have the faith. Either you (at best) have a “hard heart” or (at worst) are plain wolf among sheep.

That’s a Guilt Factory right there.

OK, that’s more than a snippet, but there’s enough more over on his site that if you’ve made it this far you should go read the whole thing.

Recommended Reading: The Journey of Ministry

Recently I’ve been reading The Journey of Ministry: Insights from a Life of Practice by Fuller seminary professor Dr. Eddie Gibbs. (Thanks go to Gibbs’ son-in-law Brian Auten (a fellow BHT patron whom I’ve had the pleasure to meet once, for far too short a conversation) for pointing it out when it was on sale.) While it seemed to start out a bit slowly, the second half of the book is chock full of good insights on the Western church and its needs in the 21st century.

A couple of choice bits:

The church also needs to multiply points of contact by taking the initiative in becoming involved in all aspects of community life and being seen making a transformative impact. We also need churches small enough for everybody to feel that they are valued, that their questions are welcomed and that they can make a contribution to expand and deepen the various expressions of ministry. The serious challenge we face today in older, traditional denominations and in many independent churches is that our model of church is not easily reproducible. It’s too expensive, consumerist and controlled. It also is increasingly out of step with a networking, relational culture.

A bit later:

The pulpit no longer provides the platform from which the neighboring community and beyond can be addressed. Its message seldom reaches beyond the dwindling ranks of the faithful, and sometimes it even falls on deaf ears in the pews.

Oh, OK, one more:

The preacher must not be allowed to become the sole interpreter of a poem. Turning poetry into prose destroys the power of the medium. It’s like explaining a joke. Poetry needs to be restored to the prophet.

Gibbs’ Chapter 6, ‘Communicating’, on the roles of apostle, prophet, evangelist, teacher, and pastor is worth the price of the book all by itself. Worth reading if you get the chance.

On Book Reviewing and Control

My friend Geof wrote a good post yesterday about really taking time to digest and consider a book before publishing a review. He appreciates his friend Adam for taking 6 months before responding to Rachel Held Evans’ book. (I’m curious whether Adam’s really been chewing on it for a while or whether he just took a while to get to the book in the first place, but that’s only tangential to Geof’s point.)

When it comes to any book review, I simply question context: who is the reviewer, and does it seem that they’ve taken the time to read it well? Often the former is easily deduced—this is the Internet—but one never really knows if a book has been carefully considered or read simply to be discarded….

…I think you need to spend time thinking about a book if you are going to lend/demand authority to your response to the reading. I think that too many high-profile theology types rush through book reviews purely knowing that their authority rests in their brand. I think that’s a dangerous mistake.

Geof has a good point here, and I wonder how my own review of Rachel’s book would change if I read it again now that I’ve had time to think and interact with others about it.

Geof omitted, though, another critical aspect of why the big-name theo-review-bloggers rush through their reads and get their reviews out early: control. These theo-review-bloggers want to direct their readers’ purchases in ways that they think are “safe”. If a critical review will keep a “dangerous” book out of hundreds of hands, let’s get it published ASAP. Waiting for six months to publish a review might allow time for those folks to buy the book, read it, and *gasp* think about it for themselves.

Don’t get me wrong - I appreciate good book recommendations, and I appreciate folks telling me when a book might be a waste of my time. But Geof is right - there’s far more authority to be had when you’ve ruminated on a book over time before reviewing than when your release-day review is ***DO NOT WANT OMG HERESY STAY AWAY***.

My 2012 reading

Time for my annual roundup of what I read over the past year. While I’m often lousy at cataloging things, this list is easy enough thanks to Goodreads and their nice little iPhone app.

(If you just want to look at the list, go check it out over on Goodreads.)

I read 59 books this year. 36 were fiction, 23 were non-fiction. Most of that non-fiction was theology, with just a couple of biographies / histories thrown in. (I need to read some more history. I don’t read enough of it anymore.)

I rated far more things with five stars this year than I have in previous years. (15 books got 5 stars! That’s more than a quarter of everything I read!) I don’t know whether that means my rating standards are slipping or that my book selection standards are improving, but at least it means I have some good books to recommend.

There are five novels I gave five stars this year:

- The Fiddler’s Gun by A. S. Peterson - a fun Revolutionary War novel focused on the adventures of a teenage girl. (I’ve got the sequel, The Fiddler’s Green, sitting in my to-read pile… should get it read in 2013 sometime.)

- The Fault in Our Stars by John Green - a short Young Adult novel focused on two teenagers who are dying of cancer. It’s not as painful as it sounds, but it’s challenging and insightful.

- Redshirts, by John Scalzi - an odd sort of meta sci-fi romp that otherwise defies comparison

- The Book of the Dun Cow by Walter Wangerin, Jr. - a fascinating fantasy story which I’m indebted to the Rabbit Room folks for recommending.

- Gathering String, by Mimi Johnson - a top-notch suspense/mystery novel whose author is a lovely lade I met once at a tweetup in Cedar Rapids.

On the non-fiction side, there were more 5-star books, but a few among those that particularly stood out:

- Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President by Candace Millard - a fascinating tale of the election and assassination of President James Garfield.

- When I Was a Child I Read Books by Marilynne Robinson. - This book of essays by the Iowa City author and professor is dense in the very best sense of the word. Thoughtful, insightful pieces on life and theology.

- An Ethic for Christians and Other Aliens in a Strange Land by William Stringfellow - powerful social critique of organizational and governmental “powers and principalities”.

I’m back at the reading for 2013, trying to finish up some Thomas Merton that I started back in December. If you’re so inclined, add me as a friend on Goodreads so we can interact about our reading throughout the year!

"When I Was A Child I Read Books" by Marilynne Robinson

I’ve gotten to the point where, unless I’m looking for a specific book, I don’t even visit the main stacks of the library any more. Instead, I head right for the “new books” section, and pick up a recent novel or biography.

While perusing the new book shelf during my last visit, I picked up Marilynne Robinson’s book of essays on a whim. It’s not the type of book I usually pick up, but it looked interesting enough, and short enough that I had a chance to get through it without getting majorly bogged down.

Marilynne Robinson teaches at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop at the U of I. She’s probably best known for her novel Gilead, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Literature in 2005. It ends up, though, that she’s published more essays than she has novels, and, if her latest volume is any indication, her essays are really good.

When I Was A Child I Read Books is a short, dense collection of essays that perhaps have less to do with reading books, and more to do with the intersection of faith and the current American religious culture. Robinson stakes out a middle ground that on one hand rejects the liberal theology of mainstream Christian denominations, while simultaneously opposing the apparent hard, uncaring line heard too often from the far right wing.

I have felt for a long time that our idea of what a human being is has grown oppressively small and dull.

Robinson’s essays call us to accept and embrace the mystery and beauty of being human. She urges us to give others the benefit of the doubt, to live with compassion towards even (especially?) those who we don’t know or understand.

There is at present a dearth of humane imagination for the integrity and mystery of other lives.

When I Was A Child I Read Books was slow going, but only because there was such richness to savor on every page. If you have the time for some thoughtful reading, I’d recommend this book.

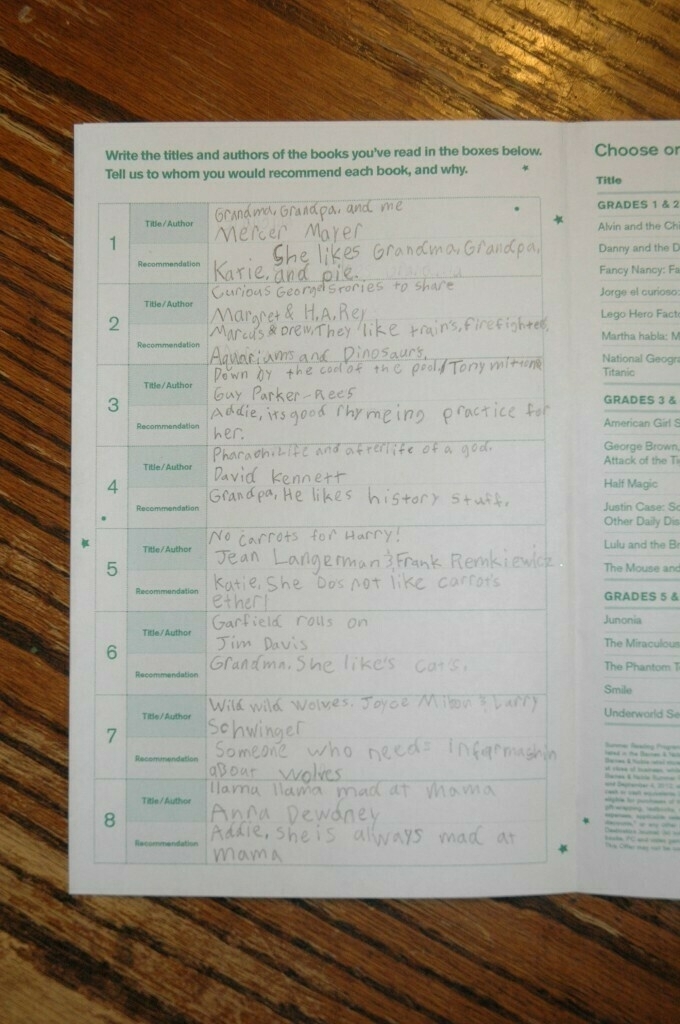

My daughter does awesome book recommendations

Forget my book recommendations, folks: my seven-year-old daughter Laura has me beat. This summer’s Barnes and Noble kids’ reading program asks the kids to list the books that they read and then who they would recommend that book for.

Here’s Laura’s response (click for a larger version):

Her recommendations, as she spelled and capitalized them: (For reference, Addie (age 6) and Katie (age 3) are her younger sisters.)

- Book Title / Author: Grandma, Grandpa, and me by Mercer Mayer. Recommended for: Katie. She likes Grandma, Grandpa, and pie.

- Book Title / Author: Curious George: Stories to share by Margret & H. A. Rey. Recommended for: Marcus & Drew. They like train’s, firefighter’s, Aquariums and Dinosaur’s.

- Book Title / Author: Down by the cool of the pool. by Tony Mitton & Guy Parker-Rees. Recommended for: Addie, its good rhymeing practice for her.

- Book Title / Author: Pharaoh. Life and afterlife of a god. by David Kennett. Recommended for: Grandpa, He likes history stuff.

- Book Title / Author: No carrots for Harry! by Jean Langerman & Frank Remkiewicz. Recommended for: Katie. She do’s not like carrot’s ether!.

- Book Title / Author: Garfield rolls on by Jim Davis. Recommended for: Grandma. She like’s cat’s.

- Book Title / Author: Wild wild wolves by Joyce Miton & Larry Schwinger. Recommended for: Someone who needs infarmashin aBout wolves.

- Book Title / Author: llama llama mad at mama by Anna Dewdney. Recommended for: Addie. She is always mad at mama

Priceless.

The Anxious Christian - Rhett Smith

Sorry for turning this into a book review blog of sorts. One of these days I’m going to get to some more serious posting. For now, though, I’m going to get the books reviewed that I need to. Bear with me.

The subtitle of Rhett Smith’s book The Anxious Christian is either a very silly rhetorical question or designed to feed the anxieties of the target audience. “Can God use your anxiety for good?” Well, of course He can. God’s ability in that regard has never really been in question. If you’re one of Smith’s anxious Christians, though, maybe your anxiety about God’s ability will drive you to buy the book.

Smith uses the early chapters of the book to recount his own struggle with anxiety as a young man. The loss of his mother and several other close relatives at an early age drove him to compulsive behaviors in an attempt to bring some control to his anxious, insecure life. Smith then explores the lessons he has learned from seeing God’s work in his life.

Christians who don’t wrestle with anxiety on a regular basis may immediately point to Phillippians 4 where Paul instructs us to “be anxious for nothing”. Smith addresses this directly in the first chapter, saying that while the instruction is “powerful” and is often counseled by those who “mean well”, we can inadvertently communicate the wrong message.

When we discourage others from safely expressing their anxiety, then we are essentially saying to them that anxiety is a bad emotion, and that it is something to be done away with. It communicates to them that perhaps something is wrong with their Christian faith…

Kierkegaard referred to anxiety as our “best teacher” because of its ability to keep us in a struggle that strives for a solution, rather than opting to forfeit the struggle and slide into a possible depression.

There, in a nutshell, is what Smith is going to come back to in nearly every chapter of the book: to recognize that God is continuously at work in us, and that our anxiety can be useful if it drives us forward to continued struggle and action. He says that God “uses [your anxiety] to awaken you and help turn you toward Him.” In chapter four he goes further to say that “God wants you to pay attention to it [anxiety]. He wants you to listen to it. For in your anxiety God is speaking to you and He is encouraging you to not stay content with where you are.”

In the last few chapters, Smith puts his experience as a marriage and family therapist to good use as he provides some practical suggestions for working in areas that often cause anxiety; he discusses setting good personal boundaries, refining personal relationships, and asking for help.

With a topic like this, an author runs the risk of playing the victim card, but Smith handles it deftly. As one who has struggled with anxiety at various times in my adult life, I appreciated the reminder that God is at work in my life. While I know it to be true, Smith’s book was a welcome kick-in-the-pants reminder.

Note: Moody Press provided me a free copy of this book asking only that I give it a fair review.

The Road Trip that Changed the World - Mark Sayers

Australian pastor and author Mark Sayers put out a request for reviews of his new book, The Road Trip that Changed the World a few weeks ago, and I’m happy today to take him up on it. I had previously read his book Vertical Self and enjoyed it quite a bit, so I was looking forward to his newest offering.

The Road Trip that Changed the World draws its title and chief topic from the classic American novel On The Road by Jack Kerouac. Sayers examines how Kerouac’s novel incited a generation to leave the ideals of home, family, and place and instead to chase the dream of the road, the hope of whatever lays just beyond the horizon.

He spends a good chapter discussing our search for the transcendent, and notes how when we fail to notice and embrace the transcendence in the material here and now, we end up constantly looking for the next “woosh” - a fleeting moment of awe that makes us feel alive but quickly leaves us searching for the next hit.

The first two-thirds of the book is devoted to this examination of the shift in American culture brought on by Kerouac; the last third brings things around to the gospel. Sayers discusses Abraham as “the first counter-cultural rebel”, and traces a path through the Old and New Testaments, ultimately concluding that we need to reject the endless search for the “woosh” over the horizon, instead finding joy and meaning and transcendence in the here and now, as we experience true community and relationship with God.

I’ll say this - Sayers has the spirit of the times nailed. If anything, I didn’t respond to it more because it already seemed so familiar. His diagnosis of cynicism, distance, and the search for transcendence in “woosh” moments is right on. His prescription of embracing community and finding transcendence in experiencing God is a call appropriate for the time. If my cynical generation is willing to hear it, The Road Trip that Changed the World is a great call back to what really matters.

Note: I was provided a free copy of the book in return for reading and posting a fair review.

Second-guessing God

Stringfellow is just full of good stuff. Still in Chapter Two of An Ethic for Christians an Other Aliens in a Strange Land, he says this about trying to understand God:

Biblical ethics do not pretend the social or political will of God; biblical politics do not implement “right” or “ultimate” answers. In this world, the judgment of God remains God’s own secret. … It is the inherent and redundant frustration of any pietistic social ethics that the ethical question is presented as a conundrum about the judgment of God in given circumstances. Human beings attempting to cope with that ethical question are certain to be dehumanized. The Bible does not pose any such riddles nor aspire to any such answers; instead, in biblical context, such queries are transposed, converted, rendered new. In the Bible, the ethical issue becomes simply: how can a person act humanly now? … Here the ethical question juxtaposes the witness of the holy nation - Jerusalem - to the other principalities, institutions and other nations - as to which Babylon is a parable. It asks: how can the Church of Jesus Christ celebrate human life in society now?

Stringfellow on Revelation

In the second chapter of William Stringfellow’s An Ethic for Christians and Other Aliens in a Strange Land, he continues to contrast the two cities mentioned in the latter half of Revelation: Babylon and Jerusalem. The Babylon of Revelation, he says, “is archetypical of all nations.” Those nations are principalities that, Stringfellow argues, by their very nature are anti-human; they serve themselves and work against that which is good. Jerusalem, on the other hand, is representative of Christians as “an embassy among the principalities” or as “a pioneer community”. (These phrases remind me instantly of N. T. Wright’s similar description of the Church in Surprised by Hope.)

But Revelation, says Stringfellow, cannot be read as a “predestinarian forecast”.

To view the Babylon material in Revelation as mechanistic prophecy - or to treat any part of the Bible in such a fashion - is an extreme distortion of the prophetic ministry….

A construction of Revelation as foreordination denies in its full implication that either principalities or persons are living beings with identities of their own and with capabilities of decision and movement respected by God. And, in the end, such superstitions demean the vocation which the Gospels attribute to Jesus Christ, rendering him a quaint automaton, rather than the Son, of God.

While my Calvinist friends will quibble with the thought that humans have “capabilities of decision and movement respected by God”, I find that last sentence to be a compelling thought - that the work of Jesus Christ redeeming the world is magnified if his work is redeeming free and willful men, and that if, as in the strong Calvinist view, the whole cosmic saga is already completely fixed in history, then Christ is, in a way, just one more player in a pre-defined role.